56 African American History Essay Topic Ideas & Examples

🏆 best african american history topic ideas & essay examples, 🔍 good essay topics on african american history, ✅ most interesting african american history topics to write about.

- African American History Timeline (1619 – 1865) As the expansion of the textile factories led irresistibly to a rise in the market for servitude Africans, there was a possibility of a slave insurrection, such as the one that prevailed in Haiti in […]

- African Americans: History and Modernity Most African Americans are descendants of enslaved people brought from Africa, and the research focuses on the connection between the current state of African Americans concerning their history. We will write a custom essay specifically for you by our professional experts 808 writers online Learn More

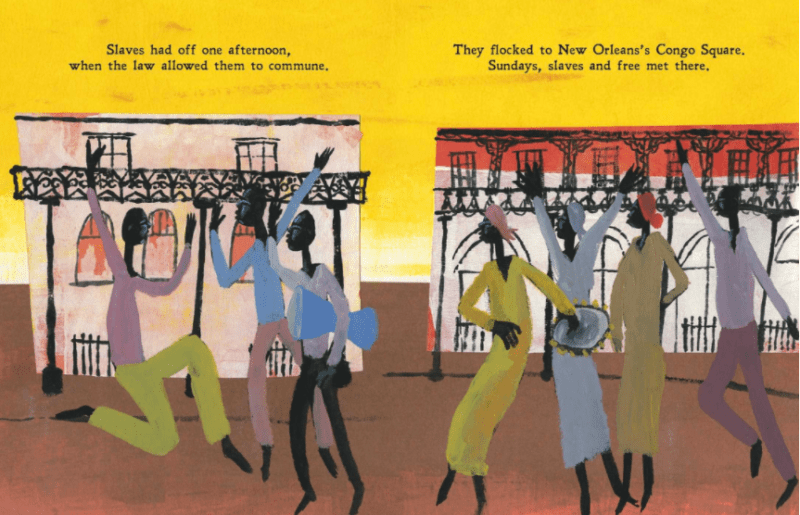

- History and True Meaning of African American Slave Music The ancestors of African Americans were forcibly separated from their homes and brought to the United States to work on the plantations of the Old South.

- The Series of Injustices Spanned the History of African Americans A series of failures for Americans began with the emergence of slavery in the USA. However, it is impossible to talk about the complete eradication of racism in the country.

- The African American History: The Historical Weight of 1776 A number of us, who arrived unexpectedly, became indentured to Virginia masters through a bidding process that was to some extent similar to later slave auctions that would become all in all widespread in the […]

- Lynching History of African Americans: An Absurd Illegal Justice System in the 19th Century Another attempt to explain the origin of lynch law is that of regulators and moderators. According to Rhodes, this theory is not applicable because the name of the law and order maintenance unit was aregulators’ […]

- African Americans Struggle Against Slavery The following paragraphs will explain in detail the two articles on slavery and the African American’s struggle to break away from the heavy and long bonds of slavery. The website tells me that Dredd Scott […]

- African American History: The Struggle for Freedom The history of the Jacksons Rainbow coalition shows the rise of the support of the African American politicians in the Democratic party.

- African American History in the 20th Century The NAACP was radical since it fought many legal battles and fought against ideologies of some of the most prominent African American leaders like those of the late Booker Washington and the government.

- African American History After Reconstruction The bureau also helped champion African Americans’ rights by pushing for the 14th and 15th amendments of the constitution that would give African Americans voting rights.

- King Jr. and Malcolm X in African American History Malcolm was able to sell his ideas to the African Americans in various meetings in the streets of Harlem and in major universities across the United States.

- Robert R. Moton’s Role in African American History In conclusion, this article has helped to get a better understanding of the topic and what events took place at that time.

- History of Higher Education for African Americans Even if I had the opportunity to participate in higher education, I could not have managed to take advantage of it since it was expensive, and I would have nothing to eat after school.

- African American History and Its Importance in Modern Days Without a clear understanding of this part of history, slavery would not have evolved to the current citizenship, freedom and human rights that we enjoy in our constitution.

- History of African Americans The readings that are going to be discussed in the paper tell the history of African Americans, their struggles for civil rights, and their integration into the social and political life of the country.

- Perspectives in African American History and Culture The point is that a person has both, mind and body, and if a person could not accept the idea of being enslaved, he/she was not a slave.

- The History of the Black Lives Matter Movement

- African American History: 1865 to the Present

- The Black History Month: The Importance of Black History

- Overview of African American History and Culture

- African American History: Religious Influences 1770 – 1831

- The Brief History of Black Nationalism

- Who Is Considered the Father of Black History

- African American History: Tribute to Sojourner Truth

- Ame and Ame Zion Churches in African American History

- Black Slaveowners in African American History

- Capitalism and Its Impact on African American History

- Education of All Perspectives of the African American History

- Changes Brewing for African American History

- Exploring African American History: The Harlem Renaissance

- Impact of the African American History on African Americans

- The Concept of Freedom in African American History

- How Does African American History Differ From Others

- African American History and “Warmth of Other Suns”

- How the 2008 Election Affected African American History

- Irene Gomez-Leon: African American History

- History of Black Wall Street ‘Little Africa’

- African American History Before 1877: Main Events and Figures

- Language Awareness: The N-Word in African American History

- Slavery and Its Significance in the African American History

- African American History During the Antebellum Period

- The Impact of the Civil War on African American History

- Analysis of Why African American History Is Important

- African American History Figure: Matthew Alexander Henson

- The Impact of Black Soldiers on American History

- The Origins and Importance of Black History Month

- Black Nationalism in African American History

- Analysis of Arguments Against Black History Month

- The Advantages and Disadvantages of Black History

- Brief History of Black Males in American Society

- Racism Enacted Throughout the History of Black Films

- The History of Harlem – Cultural Epicenter of America’s Black Community

- African American Youth and Their Lack of Interest in Black History Month

- Dark History of Medical Experimentation on Black Americans from Colonial Times

- Underrated and Unwritten Black History Heroes: John Carlos and Tommie Smith

- The Connotation of African-American History and Black History

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2024, March 2). 56 African American History Essay Topic Ideas & Examples. https://ivypanda.com/essays/topic/african-american-history-essay-topics/

"56 African American History Essay Topic Ideas & Examples." IvyPanda , 2 Mar. 2024, ivypanda.com/essays/topic/african-american-history-essay-topics/.

IvyPanda . (2024) '56 African American History Essay Topic Ideas & Examples'. 2 March.

IvyPanda . 2024. "56 African American History Essay Topic Ideas & Examples." March 2, 2024. https://ivypanda.com/essays/topic/african-american-history-essay-topics/.

1. IvyPanda . "56 African American History Essay Topic Ideas & Examples." March 2, 2024. https://ivypanda.com/essays/topic/african-american-history-essay-topics/.

Bibliography

IvyPanda . "56 African American History Essay Topic Ideas & Examples." March 2, 2024. https://ivypanda.com/essays/topic/african-american-history-essay-topics/.

- Abraham Lincoln Topics

- Black Lives Matter Topics

- American Revolution Topics

- Civil Rights Movement Questions

- Apartheid Essay Topics

- Discrimination Essay Titles

- Colonization Essay Ideas

- Civil War Titles

- Federalism Research Ideas

- Colonialism Essay Ideas

- History Topics

- Slavery Ideas

- Hard Work Research Topics

- Human Trafficking Titles

- Native American Questions

Black History Essay Topics

- Writing Essays

- Writing Research Papers

- English Grammar

- M.Ed., Education Administration, University of Georgia

- B.A., History, Armstrong State University

Black history is full of fascinating stories, rich culture, great art, and courageous acts that were undertaken within unthinkable circumstances. While Civil Rights events are the most common themes in our studies, we should resist equating Black history only with Civil Rights-era history. This list contains 50 prompts that might lead you into some interesting and little-known information about Black American history.

Note: Your first challenge in studying some of the topics below is finding resources. When conducting an internet search, be sure to place quotation marks around your search term (try different variations) to narrow your results.

- Black American newspapers

- Black Inventors

- Black soldiers in the American Revolution

- Black soldiers in the Civil War

- Buffalo Soldiers

- Buying time

- Camp Logan Riots

- Clennon Washington King, Jr.

- Coffey School of Aeronautics

- Crispus Attucks

- Domestic labor strikes in the South

- Finding lost family members after emancipation

- First African Baptist Church

- Formerly enslaved business owners

- Freedom's Journal

- Gospel music

- Gullah heritage

- Harlem Hellfighters

- Harlem Renaissance

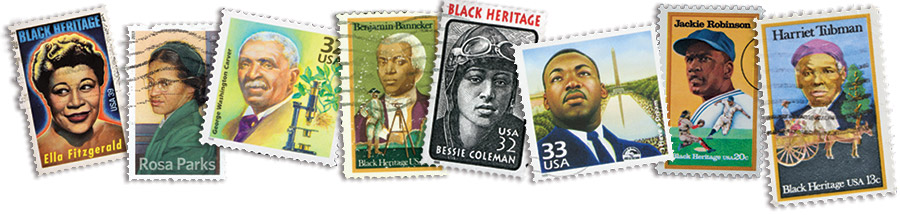

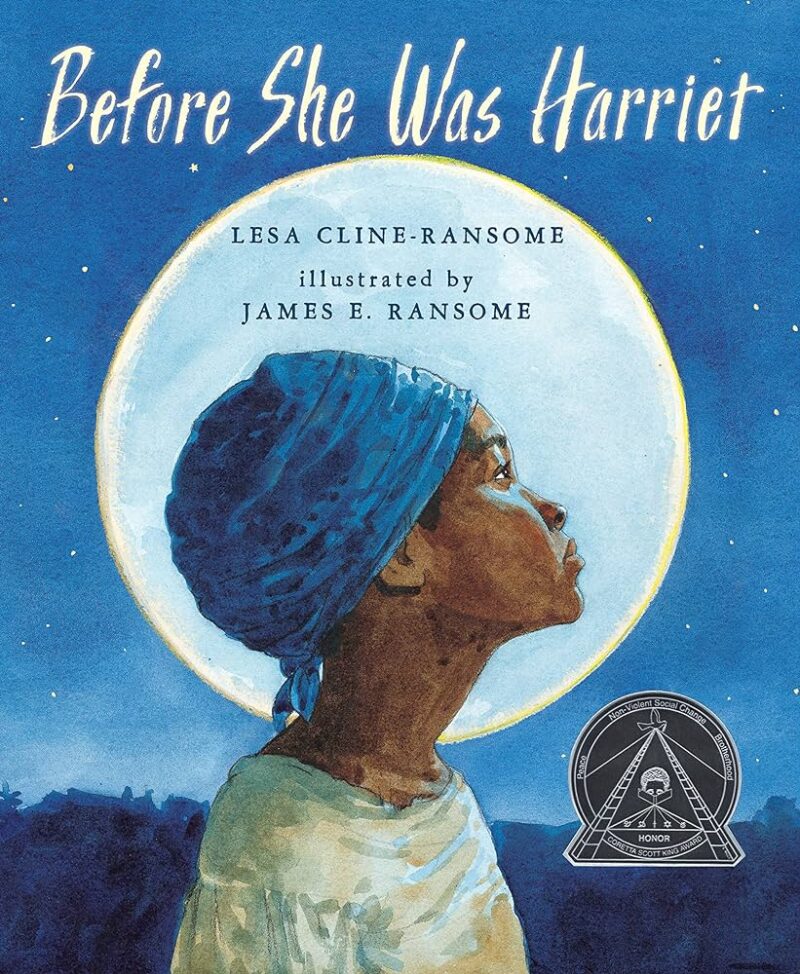

- Harriet Tubman

- Historically Black Colleges

- History of rock-and-roll

- Jumping the broom

- Manumission papers

- Maroon villages in the eighteenth century

- Motown Records

- Multi-cultural pirate ships

- Narratives by Enslaved People

- Otelia Cromwell

- Ownership of property by enslaved people

- Purchasing freedom

- Ralph Waldo Tyler

- Register of Free Persons of Color

- Secret schools in antebellum America

- Sherman's March followers

- Susie King Taylor

- The Amistad

- The Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters

- The Communist Party (involvement)

- The Great Migration

- The Haitian Revolution

- Tuskegee Airmen

- Underground Railroad

- Urban enslavement (related to buying time)

- Wilberforce College, Ohio

- Celebrating Black History Month

- Important Cities in Black History

- What Is Black History Month and How Did It Begin?

- Black History and Women's Timeline: 1900–1919

- Black History Timeline: 1700 - 1799

- Black History Timeline: 1910–1919

- Biography of Dr. Carter G. Woodson, Black Historian

- Black History Timeline: 1865–1869

- Black History Month Printables

- Black History Timeline: 1920–1929

- Little Known Important Black Americans

- Black History and Women's Timeline: 1920-1929

- Important Black Women in American History

- Black History and Women Timeline 1870-1899

- Black History Timeline: 1940–1949

- Black History from 1950–1959

- CORE CURRICULUM

- LITERACY > CORE CURRICULUM > Into Literature, 6-12" data-element-type="header nav submenu" title="Into Literature, 6-12" aria-label="Into Literature, 6-12"> Into Literature, 6-12

- LITERACY > CORE CURRICULUM > Into Reading, K-6" data-element-type="header nav submenu" title="Into Reading, K-6" aria-label="Into Reading, K-6"> Into Reading, K-6

- INTERVENTION

- LITERACY > INTERVENTION > English 3D, 4-12" data-element-type="header nav submenu" title="English 3D, 4-12" aria-label="English 3D, 4-12"> English 3D, 4-12

- LITERACY > INTERVENTION > Read 180, 3-12" data-element-type="header nav submenu" title="Read 180, 3-12" aria-label="Read 180, 3-12"> Read 180, 3-12

- LITERACY > READERS > Hero Academy Leveled Libraries, PreK-4" data-element-type="header nav submenu" title="Hero Academy Leveled Libraries, PreK-4" aria-label="Hero Academy Leveled Libraries, PreK-4"> Hero Academy Leveled Libraries, PreK-4

- LITERACY > READERS > HMH Reads Digital Library, K-5" data-element-type="header nav submenu" title="HMH Reads Digital Library, K-5" aria-label="HMH Reads Digital Library, K-5"> HMH Reads Digital Library, K-5

- LITERACY > READERS > inFact Leveled Libraries, K-5" data-element-type="header nav submenu" title="inFact Leveled Libraries, K-5" aria-label="inFact Leveled Libraries, K-5"> inFact Leveled Libraries, K-5

- LITERACY > READERS > Rigby PM, K-5" data-element-type="header nav submenu" title="Rigby PM, K-5" aria-label="Rigby PM, K-5"> Rigby PM, K-5

- LITERACY > READERS > Science & Engineering Leveled Readers, K-5" data-element-type="header nav submenu" title="Science & Engineering Leveled Readers, K-5" aria-label="Science & Engineering Leveled Readers, K-5"> Science & Engineering Leveled Readers, K-5

- SUPPLEMENTAL

- LITERACY > SUPPLEMENTAL > A Chance in the World SEL, 8-12" data-element-type="header nav submenu" title="A Chance in the World SEL, 8-12" aria-label="A Chance in the World SEL, 8-12"> A Chance in the World SEL, 8-12

- LITERACY > SUPPLEMENTAL > Amira Learning, K-6" data-element-type="header nav submenu" title="Amira Learning, K-6" aria-label="Amira Learning, K-6"> Amira Learning, K-6

- LITERACY > SUPPLEMENTAL > Classcraft, K-8" data-element-type="header nav submenu" title="Classcraft, K-8" aria-label="Classcraft, K-8"> Classcraft, K-8

- LITERACY > SUPPLEMENTAL > JillE Literacy, K-3" data-element-type="header nav submenu" title="JillE Literacy, K-3" aria-label="JillE Literacy, K-3"> JillE Literacy, K-3

- LITERACY > SUPPLEMENTAL > Waggle, K-8" data-element-type="header nav submenu" title="Waggle, K-8" aria-label="Waggle, K-8"> Waggle, K-8

- LITERACY > SUPPLEMENTAL > Writable, 3-12" data-element-type="header nav submenu" title="Writable, 3-12" aria-label="Writable, 3-12"> Writable, 3-12

- LITERACY > SUPPLEMENTAL > ASSESSMENT" data-element-type="header nav submenu" title="ASSESSMENT" aria-label="ASSESSMENT"> ASSESSMENT

- MATH > CORE CURRICULUM > Arriba las Matematicas, K-8" data-element-type="header nav submenu" title="Arriba las Matematicas, K-8" aria-label="Arriba las Matematicas, K-8"> Arriba las Matematicas, K-8

- MATH > CORE CURRICULUM > Go Math!, K-6" data-element-type="header nav submenu" title="Go Math!, K-6" aria-label="Go Math!, K-6"> Go Math!, K-6

- MATH > CORE CURRICULUM > Into Algebra 1, Geometry, Algebra 2, 8-12" data-element-type="header nav submenu" title="Into Algebra 1, Geometry, Algebra 2, 8-12" aria-label="Into Algebra 1, Geometry, Algebra 2, 8-12"> Into Algebra 1, Geometry, Algebra 2, 8-12

- MATH > CORE CURRICULUM > Into Math, K-8" data-element-type="header nav submenu" title="Into Math, K-8" aria-label="Into Math, K-8"> Into Math, K-8

- MATH > CORE CURRICULUM > Math Expressions, PreK-6" data-element-type="header nav submenu" title="Math Expressions, PreK-6" aria-label="Math Expressions, PreK-6"> Math Expressions, PreK-6

- MATH > CORE CURRICULUM > Math in Focus, K-8" data-element-type="header nav submenu" title="Math in Focus, K-8" aria-label="Math in Focus, K-8"> Math in Focus, K-8

- MATH > SUPPLEMENTAL > Classcraft, K-8" data-element-type="header nav submenu" title="Classcraft, K-8" aria-label="Classcraft, K-8"> Classcraft, K-8

- MATH > SUPPLEMENTAL > Waggle, K-8" data-element-type="header nav submenu" title="Waggle, K-8" aria-label="Waggle, K-8"> Waggle, K-8

- MATH > INTERVENTION > Math 180, 5-12" data-element-type="header nav submenu" title="Math 180, 5-12" aria-label="Math 180, 5-12"> Math 180, 5-12

- SCIENCE > CORE CURRICULUM > Into Science, K-5" data-element-type="header nav submenu" title="Into Science, K-5" aria-label="Into Science, K-5"> Into Science, K-5

- SCIENCE > CORE CURRICULUM > Into Science, 6-8" data-element-type="header nav submenu" title="Into Science, 6-8" aria-label="Into Science, 6-8"> Into Science, 6-8

- SCIENCE > CORE CURRICULUM > Science Dimensions, K-12" data-element-type="header nav submenu" title="Science Dimensions, K-12" aria-label="Science Dimensions, K-12"> Science Dimensions, K-12

- SCIENCE > READERS > inFact Leveled Readers, K-5" data-element-type="header nav submenu" title="inFact Leveled Readers, K-5" aria-label="inFact Leveled Readers, K-5"> inFact Leveled Readers, K-5

- SCIENCE > READERS > Science & Engineering Leveled Readers, K-5" data-element-type="header nav submenu" title="Science & Engineering Leveled Readers, K-5" aria-label="Science & Engineering Leveled Readers, K-5"> Science & Engineering Leveled Readers, K-5

- SCIENCE > READERS > ScienceSaurus, K-8" data-element-type="header nav submenu" title="ScienceSaurus, K-8" aria-label="ScienceSaurus, K-8"> ScienceSaurus, K-8

- SOCIAL STUDIES > CORE CURRICULUM > HMH Social Studies, 6-12" data-element-type="header nav submenu" title="HMH Social Studies, 6-12" aria-label="HMH Social Studies, 6-12"> HMH Social Studies, 6-12

- SOCIAL STUDIES > SUPPLEMENTAL > Writable" data-element-type="header nav submenu" title="Writable" aria-label="Writable"> Writable

- For Teachers

- PROFESSIONAL DEVELOPMENT > For Teachers > Coachly" data-element-type="header nav submenu" title="Coachly" aria-label="Coachly"> Coachly

- PROFESSIONAL DEVELOPMENT > For Teachers > Teacher's Corner" data-element-type="header nav submenu" title="Teacher's Corner" aria-label="Teacher's Corner"> Teacher's Corner

- PROFESSIONAL DEVELOPMENT > For Teachers > Live Online Courses" data-element-type="header nav submenu" title="Live Online Courses" aria-label="Live Online Courses"> Live Online Courses

- For Leaders

- PROFESSIONAL DEVELOPMENT > For Leaders > The Center for Model Schools (formerly ICLE)" data-element-type="header nav submenu" title="The Center for Model Schools (formerly ICLE)" aria-label="The Center for Model Schools (formerly ICLE)"> The Center for Model Schools (formerly ICLE)

- MORE > undefined > Assessment" data-element-type="header nav submenu" title="Assessment" aria-label="Assessment"> Assessment

- MORE > undefined > Early Learning" data-element-type="header nav submenu" title="Early Learning" aria-label="Early Learning"> Early Learning

- MORE > undefined > English Language Development" data-element-type="header nav submenu" title="English Language Development" aria-label="English Language Development"> English Language Development

- MORE > undefined > Homeschool" data-element-type="header nav submenu" title="Homeschool" aria-label="Homeschool"> Homeschool

- MORE > undefined > Intervention" data-element-type="header nav submenu" title="Intervention" aria-label="Intervention"> Intervention

- MORE > undefined > Literacy" data-element-type="header nav submenu" title="Literacy" aria-label="Literacy"> Literacy

- MORE > undefined > Mathematics" data-element-type="header nav submenu" title="Mathematics" aria-label="Mathematics"> Mathematics

- MORE > undefined > Professional Development" data-element-type="header nav submenu" title="Professional Development" aria-label="Professional Development"> Professional Development

- MORE > undefined > Science" data-element-type="header nav submenu" title="Science" aria-label="Science"> Science

- MORE > undefined > undefined" data-element-type="header nav submenu">

- MORE > undefined > Social and Emotional Learning" data-element-type="header nav submenu" title="Social and Emotional Learning" aria-label="Social and Emotional Learning"> Social and Emotional Learning

- MORE > undefined > Social Studies" data-element-type="header nav submenu" title="Social Studies" aria-label="Social Studies"> Social Studies

- MORE > undefined > Special Education" data-element-type="header nav submenu" title="Special Education" aria-label="Special Education"> Special Education

- MORE > undefined > Summer School" data-element-type="header nav submenu" title="Summer School" aria-label="Summer School"> Summer School

- BROWSE RESOURCES

- BROWSE RESOURCES > Classroom Activities" data-element-type="header nav submenu" title="Classroom Activities" aria-label="Classroom Activities"> Classroom Activities

- BROWSE RESOURCES > Customer Success Stories" data-element-type="header nav submenu" title="Customer Success Stories" aria-label="Customer Success Stories"> Customer Success Stories

- BROWSE RESOURCES > Digital Samples" data-element-type="header nav submenu" title="Digital Samples" aria-label="Digital Samples"> Digital Samples

- BROWSE RESOURCES > Events" data-element-type="header nav submenu" title="Events" aria-label="Events"> Events

- BROWSE RESOURCES > Grants & Funding" data-element-type="header nav submenu" title="Grants & Funding" aria-label="Grants & Funding"> Grants & Funding

- BROWSE RESOURCES > International" data-element-type="header nav submenu" title="International" aria-label="International"> International

- BROWSE RESOURCES > Research Library" data-element-type="header nav submenu" title="Research Library" aria-label="Research Library"> Research Library

- BROWSE RESOURCES > Shaped - HMH Blog" data-element-type="header nav submenu" title="Shaped - HMH Blog" aria-label="Shaped - HMH Blog"> Shaped - HMH Blog

- BROWSE RESOURCES > Webinars" data-element-type="header nav submenu" title="Webinars" aria-label="Webinars"> Webinars

- CUSTOMER SUPPORT

- CUSTOMER SUPPORT > Contact Sales" data-element-type="header nav submenu" title="Contact Sales" aria-label="Contact Sales"> Contact Sales

- CUSTOMER SUPPORT > Customer Service & Technical Support Portal" data-element-type="header nav submenu" title="Customer Service & Technical Support Portal" aria-label="Customer Service & Technical Support Portal"> Customer Service & Technical Support Portal

- CUSTOMER SUPPORT > Platform Login" data-element-type="header nav submenu" title="Platform Login" aria-label="Platform Login"> Platform Login

- Learn about us

- Learn about us > About" data-element-type="header nav submenu" title="About" aria-label="About"> About

- Learn about us > Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion" data-element-type="header nav submenu" title="Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion" aria-label="Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion"> Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion

- Learn about us > Environmental, Social, and Governance" data-element-type="header nav submenu" title="Environmental, Social, and Governance" aria-label="Environmental, Social, and Governance"> Environmental, Social, and Governance

- Learn about us > News Announcements" data-element-type="header nav submenu" title="News Announcements" aria-label="News Announcements"> News Announcements

- Learn about us > Our Legacy" data-element-type="header nav submenu" title="Our Legacy" aria-label="Our Legacy"> Our Legacy

- Learn about us > Social Responsibility" data-element-type="header nav submenu" title="Social Responsibility" aria-label="Social Responsibility"> Social Responsibility

- Learn about us > Supplier Diversity" data-element-type="header nav submenu" title="Supplier Diversity" aria-label="Supplier Diversity"> Supplier Diversity

- Join Us > Careers" data-element-type="header nav submenu" title="Careers" aria-label="Careers"> Careers

- Join Us > Educator Input Panel" data-element-type="header nav submenu" title="Educator Input Panel" aria-label="Educator Input Panel"> Educator Input Panel

- Join Us > Suppliers and Vendors" data-element-type="header nav submenu" title="Suppliers and Vendors" aria-label="Suppliers and Vendors"> Suppliers and Vendors

- Divisions > Center for Model Schools (formerly ICLE)" data-element-type="header nav submenu" title="Center for Model Schools (formerly ICLE)" aria-label="Center for Model Schools (formerly ICLE)"> Center for Model Schools (formerly ICLE)

- Divisions > Heinemann" data-element-type="header nav submenu" title="Heinemann" aria-label="Heinemann"> Heinemann

- Divisions > NWEA" data-element-type="header nav submenu" title="NWEA" aria-label="NWEA"> NWEA

- Platform Login

SOCIAL STUDIES

PROFESSIONAL DEVELOPMENT

Activities & Lessons

8 Black History Month Writing Prompts

Illustration (featured from left to right): James Baldwin , Amy Sherald, Katherine Johnson, Kimberly Bryant, and Stevie Wonder

Black history should never be relegated to a date on a calendar. It is too intricately woven into the meaning of America. What would the United States be without the muscle, skill, and innovative thinking of its Black citizens?

Inventor and agricultural scientist George Washington Carver said, “When you do the common things in life in an uncommon way, you will command the attention of the world.” This quote captures the theme of a year-round focus on Black history in my fourth grade African-centered classroom. My students and I spend time marveling at the ingenuity of countless Black people who have faced, and continue to face, all too common dehumanizing circumstances and yet continue to rise.

I pose the question, “How are people who look like you overcoming problems in their daily life?” My students and I ground the question in three ways. First, we identify, research, and interview innovative people we know locally (caregivers, family members, friends, business owners, city officials). Then, we research national celebrities and other prominent figures. Finally, we explore the presence of Black ingenuity and innovation on a global scale.

Black History Month for my classroom is simply a time to recommit to the Black historical legacy of ingenuity and innovation in the face of racism and other systems of oppression. I hope these Black history writing prompts help you do the same with your class, in February and all year round.

Black History Month Journal Prompts

Introduce your students to the Black innovators highlighted here. Think of their experiences and perspectives as a springboard for students to write about their own lives. Note that the structure of each prompt asks students to do three things: delve into the life and accomplishments of a Black innovator; talk over a quote by or about the person; and finally, tackle a related writing prompt. Each prompt guides students into a particular type of writing, such as personal narrative, informative, or persuasive.

Black History Writing Prompt #1

Spotlight On: NASA Mathematician Katherine Johnson Text Type: Personal Narrative

Background: Tell students that Katherine Johnson (1918–2020) was a mathematician for NASA. She calculated rocket paths for space missions. Her work was critical to the success of several human spaceflights, including the Friendship 7 mission that made astronaut John Glenn the first American to orbit Earth. Glenn’s flight marked a turning point in the space race between the U.S. and the Soviet Union (today, Russia). In 2015, President Barack Obama awarded Johnson the Presidential Medal of Freedom for her life’s work. The 2017 movie Hidden Figures tells the story of Johnson and two other unsung heroes of NASA’s early days.

Talk It Over: Tell students that in 1962, astronaut John Glenn requested that Johnson double check the computer-generated trajectory of Friendship 7’s Earth orbit. “If she says the numbers are good,” he declared, “I’m ready to go.” Ask: How do you know Glenn had confidence in Johnson? Do you think she had confidence in herself? What makes you say that?

Writing Prompt: Think about a time in your life when someone had confidence in you to solve a problem or complete a task. That person might be a family member, friend, teacher, coach, pastor, or even a stranger. Write a personal narrative about the experience. Be sure to describe the task and the effect that person’s confidence had on you. Include sensory details and an organized story structure.

Black History Writing Prompt #2

Spotlight On: Author James Baldwin Text Type: Persuasive/Opinion Writing

Background: Tell students that James Baldwin (1924–1987) wrote novels, essays, plays, and short stories that forced readers to confront racism in America. Baldwin lived during a time when our government wrote laws to keep Black and white people separated in public places, like schools, restaurants, and churches. The impact of racism drove Baldwin to move to France. His 1953 novel Go Tell It on the Mountain is considered an American classic.

Talk It Over: Read aloud this quote by Baldwin: "I knew I was Black, of course, but I also knew I was smart. I didn't know how I would use my mind, or even if I could, but that was the only thing I had to use.” Ask: Why do you think Baldwin says he didn’t know if he could use his mind? (Baldwin is saying that racism tries to make Black people feel like they aren’t smart. He eventually used his mind to become a great writer who fought against racism with his words.) How can we apply Baldwin’s quote to education? How might racism affect what we’re taught in school? What effect might it have on the way students learn?

Writing Prompt: Write a five-paragraph persuasive essay arguing for ways to improve your least favorite or favorite subject. Be sure to explain how the change will help improve your motivation and thinking. When you are finished editing and revising, send the essay to your parents, teacher, principal, superintendent, and school board.

Black History Writing Prompt #3

Spotlight On: Actor/Writer/Producer Tyler Perry Text Type: Informative Writing

Background: Tell students that Tyler Perry (1969–) is the mastermind behind popular plays, movies, TV shows, and New York Times bestselling books. He portrayed his most famous character, Madea, in plays that eventually made the leap to the big screen, with the franchise grossing more than $500 million. Popular TV shows like The Walking Dead and blockbuster movies like Black Panther were shot at Tyler Perry Studios, in Atlanta, Georgia. But Perry’s success belies a difficult childhood that almost destroyed him. His father often beat him, which Perry says led him to attempt suicide. In his early 20s, he saw an episode of The Oprah Winfrey Show in which Oprah described the therapeutic effect of writing. Perry started writing down everything that happened to him. He believes writing saved his life.

Talk It Over: Read aloud this quote by Perry: “ My biggest success is getting over the things that have tried to destroy and take me out of this life. Those are my biggest successes. It has nothing to do with work.” Remind students that Perry uses writing as therapy. Ask: Do you agree with Perry’s idea of “success”? Explain.

Writing Prompt: Think about a hobby or interest that brings you calm, such as cooking, coding, dancing, or drawing. Write an informative essay, create a brochure, or design a PowerPoint presentation that describes the benefits of the activity and how it affects your state of mind.

Black History Writing Prompt #4

Spotlight On: Artist Amy Sherald Text Type: Poetry

Background: Tell students that First Lady Michelle Obama chose Amy Sherald (1973–) to paint Mrs. Obama’s official portrait for the National Portrait Gallery shortly after Sherald won the 2016 Outwin Boochever Portrait Competition. Mrs. Obama described an immediate connection upon meeting Sherald, feeling "blown away by the boldness of her colors and the uniqueness of her subject matter.” But not everyone likes such bold paintings. Sherald received quite a bit of flack for the portrait. Her vision of how to paint the first African-American First Lady wasn’t typical, and this is partly what makes her an innovator.

Talk It Over: Read aloud Sherald’s response to those who didn’t understand her painting style: “Some people like their poetry to rhyme. Some people don’t; that’s fine. It’s cool.” Ask: What is Sherald saying about people’s taste in art? How does Sherald view art? What do you think about the portrait of the First Lady ? What do you think people objected to?

Writing Prompt: Write a poem of three or more lines, rhyming or not, that captures an emotion in vivid detail. Think about a strong emotion you’ve experienced lately. It could be how you felt when you saw Sherald’s portrait of First Lady Michelle Obama, or the feeling of learning how people reacted against it. If you’d like to write about something more personal, consider writing about how you felt on a recent Zoom call, or when a parent or caregiver reprimanded or praised you. What emotion did you feel? Close your eyes and try to visualize what you remember.

Black History Writing Prompt #5

Spotlight On: Electrical Engineer Kimberly Bryant Text Type: Textual Analysis

Background: Tell students that Kimberly Bryant (1967–) is an electrical engineer who worked in biotechnology for companies including Genentech, Novartis Vaccines and Diagnostics, and Merck. In 2011, she founded the nonprofit Black Girls Code to teach basic programming to Black girls who are underrepresented in technology careers. Bryant has been listed as one of the "25 Most Influential African-Americans in Technology."

Talk It Over: Read aloud this quote by Kimberly Bryant: “You can absolutely be what you can't see! That's what innovators and disruptors do.” Ask: What makes Bryant an innovator and disrupter? How could you be an innovator and create solutions to the problems you see around you? How could you disrupt unfairness that you see? Could you use a hobby or talent to innovate and disrupt?

Writing Prompt: Visit the Black Girls Code site. Scan the homepage and write down the following:

- Company slogan

- One-sentence summary of the company’s vision

- The headline of one article that appears on the site

- A summary of the article’s central points

- A description of the article’s purpose (i.e. entertain, inform, persuade, examine/explore an issue, describe/report, instruct), along with evidence from the text to support your claim

Learn code or create your own website that highlights the thing you love to do and that makes you different from everyone else. You might consider using the website as a way to innovate or disrupt. Keep the website updated weekly.

Black History Writing Prompt #6

Spotlight On: Singer/Songwriter Stevie Wonder Text Type: Research Writing

Background: Stevie Wonder (1950–) is a pioneer in the music industry who never let his blindness stop him from achieving anything he wanted in life. To date, the singer-songwriter has picked up 25 Grammy Awards and an Oscar, sold over 100 million records worldwide, and has been inducted into the Rock & Roll and Songwriters Halls of Fame. The release of his song "Happy Birthday" in 1980, followed by tireless campaigning, led to the establishment of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. Day in 1986. A tech-savvy musician himself, Wonder has pushed for advancements that make technology accessible for blind and deaf people.

Talk It Over: Read aloud this quote by Stevie Wonder: “Do you know, it's funny, but I never thought of being blind as a disadvantage, and I never thought of being Black as a disadvantage.” Ask: Does this quote surprise you? Why or why not? Why might some people see being blind or Black as a disadvantage? How might technology help address disability or racism?

Writing Prompt: Think about the problems we face today—from racism to blindness to COVID-19, cancer, global warming, bullying, over-policing, you name it. Choose one of the problems and conduct research to answer these questions:

- What is the problem? Describe it.

- Who is this problem affecting most?

- Who are the experts trying to solve the problem?

- What technology are they creating to solve the problem?

- What are the pros and cons of the technology?

Black History Writing Prompt #7

Spotlight On: Rapper Kendrick Lamar Text Type: Interview

Background: Tell students that Kendrick Lamar (1987–) has won 13 Grammy Awards, two American Music Awards, five Billboard Music Awards, a Brit Award, 11 MTV Video Music Awards, a Pulitzer Prize, and an Academy Award nomination. In 2015, he received the California State Senate's Generational Icon award. Three of his studio albums have been listed in Rolling Stone 's "The 500 Greatest Albums of All Time (2020)."

Talk It Over: Share this quote by Lamar with your students: “It took a long time for people to embrace us (rappers)—people outside of our community, our culture—to see this not just as vocal lyrics, but to see that this is really pain, this is really hurt, this is really true stories of our lives on wax.” Ask: Why do you think people like different genres of music? Why do you think some people, after 50 years, still don’t view rap as real music?

Writing Prompt: Think about three people you know who are different in some way. Their differences can be based on demographics like race, age, gender, sexual orientation, religion, or ability. Choose one demographic (age, for example) and interview three people based on that demographic (a child, an adult, an elderly person) using these two questions:

- What is your favorite genre of music?

- What do you think about rap music?

Record your interview and type your transcript. Present your findings to the class in the form of a newscast using a video recording app. Your newscast should be pre-recorded. Finally, record 30 seconds at the end talking about how each interviewees’ perspective is similar and different.

Black History Writing Prompt #8

Spotlight On: Science Fiction Author Octavia E. Butler Text Type: Science Fiction Writing

Background: Tell students that Octavia E. Butler (1947–2006) wrote science fiction novels that blend mysticism, mythology, and African American spiritualism. Her work has garnered numerous awards. In 1995, she became the first science fiction writer to receive a MacArthur Foundation award, or “genius grant,” and in 2000 she won a PEN Award for lifetime achievement. In 2010, she was inducted into the Science Fiction Hall of Fame.

Talk It Over: Read aloud this quote by Octavia Butler: “If you want a thing — truly want it, want it so badly that you need it as you need air to breathe, then unless you die, you will have it. Why not? It has you…” Ask: What does she mean when she talks about wanting a thing the way you need air to breathe? What is she telling us about the things that drive us?

Writing Prompt: Imagine that it’s 30 years in the future. Will people be living on Mars? Will we have flying cars? Will there still be poverty, or racism? Write a one-page fantasy story in which the Earth is threatened with certain destruction. You as the main character must use your superpower to save the world. Your superpower is whatever you are passionate about—music, debating, helping people, athletics, acting, writing, designing, or something else entirely. You can do things with your superpower that are unreal. The human race is counting on you. Good luck!

More Ideas for Black History Writing Prompts

This post focused on Black ingenuity and innovation. Have any other theme ideas for Black History Month writing prompts? Share them with us on Twitter ( @TheTeacherRoom ) or Facebook .

The views expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily represent those of HMH.

Try Writable to support your ELA curriculum, district benchmarks, and state standards with more than 600 fully customizable writing assignments and rubrics for students in Grades 3-12.

Download our FREE 2022–2023 calendar of activities.

- Activities & Lessons

- Social Studies

- Grades 9-12

Related Reading

What Is Academic Vocabulary?

Jennifer Corujo Shaped Editor

March 25, 2024

Podcast: Partnering with Families to Build Early Literacy Skills with Melissa Hawkins in HI on Teachers in America

March 21, 2024

2024 Happy Teacher Appreciation Week Ideas

Brenda Iasevoli Shaped Executive Editor

March 20, 2024

54 Super Inspiring Black History Month Writing Prompts

By: Author Valerie Forgeard

Posted on Published: October 10, 2022 - Last updated: July 1, 2023

Categories Creativity , History , Inspiration , Society , Writing

Are you looking for a way to get inspired this Black History Month? If so, you’re in luck! In this blog post, we will be discussing 54 writing prompts that will help get your creative juices flowing. Whether you are a student who needs to write a paper or an adult who wants to reflect on the progress that has been made, these prompts will help you celebrate black history in a meaningful way.

54 Black History Month Writing Prompts

- Write about what Black History Month means to you.

- Write about the importance of recognizing the contributions of black people in history.

- Write about your favorite black personalities and why they’re so important to you.

- Write about your favorite black character in history and why they inspire you so much.

- Write an acrostic poem about the life of a black historical figure. What’s their story? How did they overcome adversity? How can you identify with their experiences?

- Write a letter to a black historical figure and tell them how their work has impacted you personally. Tell them what they meant to you and how you want to carry on their legacy.

- Write about how you learned about the Black Lives Matter movement and what it meant to you then and now.

- Write about your favorite Black History Month activity.

- Describe how you celebrate Black History Month.

- Write about what it means to be black in the United States – and how we can change that!

- Write about how you once made an assumption about a person based on your appearance that turned out wrong.

- Write a list of your favorite black heroes.

- Describe how you can use your skills to help your community.

- Write down what you learned from a black role model or why it’s important to you.

- Write about a time when you felt like you didn’t belong.

- Write about an important moment in black history that was overlooked by society or misrepresented by mainstream media.

- Write about your favorite black movie or show on TV and why it’s your favorite (or if there’s more than one).

- Write about what it would be like if there were no more racism against people because of their race.

- Write about what’s changed since the civil rights movement and what hasn’t changed yet.

- Write about how you can ensure that Black History Month isn’t just a month a year but something that’s integrated into our daily lives as Americans who’re proud of our African American heritage!

- Write about your favorite Black History Month song.

- Describe an event in Black history that inspires you.

- Write about the many ways black people have impacted the world.

- Write about the history of the civil rights movement.

- Write about a black woman who stood up against racism.

Questions to Inspire You to Write About Black History Month

- How do you feel about Black History Month?

- What’s your favorite memory of a black person?

- How have you learned about your African heritage?

- What does being African American mean to you?

- What is the most important thing that’s happened to the African American community in the last century?

- What’s an important lesson you’ve learned from black history?

- If you could be a black historical figure like Martin Luther King Jr or Frederick Douglass, who’d it be and why?

- What’s the main idea behind Black History Month?

- How do you honor Black History Month?

- Why do you think it’s important to learn about black history?

- How has learning about black history impacted your life?

- Where did African American culture come from?

- If you could go back in time and meet a black historical figure, who’d it be and why?

- If there was one thing that people could learn about black history from reading your story, what would it be? And why?

- What were some of the most important moments in black history?

- What does it mean for a society that we still have to fight for equality?

- What did you learn about black history that surprised you?

- Who’re your favorite Black people, and why are they so important to you?

- What creative ways are there to celebrate Black History Month in your classroom or school?

- If I could meet one African American from history, who’d it be and why?

- What would society look like if this person hadn’t lived?

- If Martin Luther King, Jr. were alive today, how do you think he’d feel about race relations in the world today?

- How have the lives of African Americans changed in the last 10 years?

- Why is George Washington Carver an important figure in black history?

- What’re the best books you’ve read to understand black history?

- What do you think about how black people are portrayed in the media?

- If you could go back in time, what would you tell your ancestors about being black in America?

- What challenges does the African American community face today?

- Why is it important to know and recognize the accomplishments of black Americans?

Black History Month Activity Ideas

Black History Month is a time to celebrate the achievements of the black American community and learn more about American history. It’s also an opportunity to educate others about blacks’ role in American history, especially during the Civil Rights Movement.

Here are some activities you can do during Black History Month:

- Watch movies or documentaries about important figures in black history, such as Martin Luther King Jr, Harriet Tubman, or Rosa Parks.

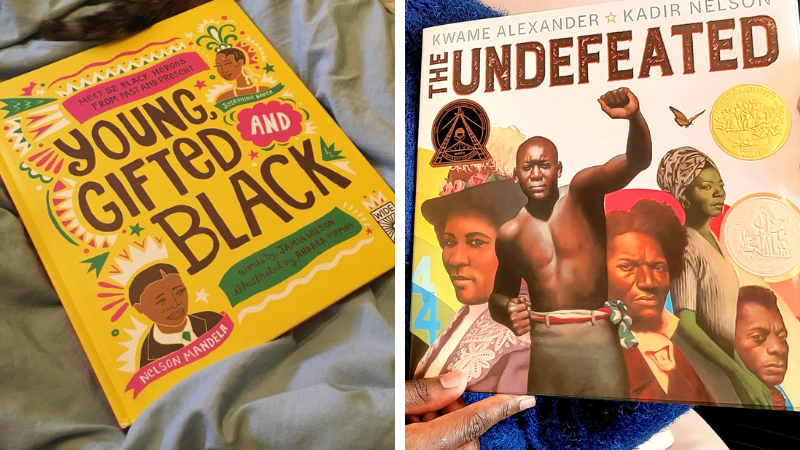

- Read books by or about black authors or figures. If you’re looking for good books to read, check out our list of 75 must-read books by African American authors.

- Visit a site related to African American history, such as the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture in Washington, D.C.

- Attend a performance at an arts center featuring African Americans music and dance. In February, you may find performances at local schools or community centers, as they often host events during Black History Month.

- Make artwork inspired by African American culture using materials such as fabric scraps and glue sticks. You can use your creations as decorations for your home or give them as gifts.

- Learn to dance like Michael Jackson, James Brown, or Beyoncé Knowles.

Black History Month is a time to recognize the contributions of African Americans to the history of the United States and the world. It’s also a time to learn about those who came before us and see how they’ve shaped our lives and society today.

We must remember that many of our institutions were built by black people who were enslaved and who, until recently, received no recognition for their work or ideas. That’s why it’s important to recognize these historical figures during Black History Month, so they aren’t forgotten.

Black History Month encourages us to have important conversations about race in the United States and worldwide – and if we don’t have these conversations enough at other times of the year, it offers us all the opportunity to start them now!

43 Black History Month Writing Prompts

The month of February is Black History Month in the United States.

This is a time for African-Americans to celebrate their achievements and role within the U.S.

Studying Black History is an important part of your education because it provides historical context for the journey of African-Americans while also highlighting the problems they still face today.

Below, you will find a list of prompts that will help improve your writing skills as well as gain a deeper understanding of Black history.

Using This Guide

First and foremost, it’s important to research your topic when writing about historical events or holidays.

Once you’ve done that, you can use these prompts however you’d like.

But if you’re unsure of just how to get started, here is a list of creative ways that you can use this guide:

- Pick a random number and use that prompt.

- Choose a topic you’re unsure about. Research it, and then write about it.

- Ask a friend or family member to pick a prompt for you.

Time to Pick a Prompt

- Why is George Washington Carver an important figure in Black history?

- Do you think schools should teach more Black history?

- One way that I can help prevent discrimination is…

- Pick a Black woman in history, and write a few paragraphs about her.

- Who is your favorite Black musician? Why?

- Martin Luther King Jr.’s “I have a dream” speech is arguably his most notable speech. What is your dream for the world?

- If you could interview one influential Black person, who would it be? What would you ask them?

- Name two inventions created by Black Americans. How are they significant in your life today?

- What do you think a world without racism could look like?

- Who is your favorite Black actor? Why?

- Research a Black poet, and write about what your favorite poem means to you.

- How did the Civil Rights Movement change the world?

- Why do we celebrate Black history?

- How would you feel if you weren’t allowed to go to the same places or use the same things as your friend?

- What would you have done to help Harriet Tubman?

- Why do you think it took so long for the U.S. to have a Black president?

- Describe racism in your own words.

- Write a poem about racial injustice.

- What are some creative ways your class or school could celebrate Black History Month?

- Who is your favorite Black athlete? Why?

- What inspires you to be a better person?

- Why was Rosa Parks an influential person in American History?

- Pick a local Black-owned business, and write an advertisement for them.

- Write a few paragraphs about why the Black Lives Matter movement is an important step toward equality.

- Write about a time when you were treated unfairly for something that is out of your control. How did you feel?

- Does your family talk about racism?

- What is the most important thing you’ve learned during Black History Month?

- What do you think it would have been like to be at the Emancipation Proclamation speech?

- In what ways do you think the media incorrectly depicts Black Americans?

- Research Ruth Lloyd, and write 3-4 paragraphs about what you’ve learned.

- Write a poem about segregation.

- Research the Harlem Renaissance. What do you think is the most important cultural contribution to come from it?

- Write 3-4 paragraphs about the significance of Kamala Harris as the Vice President.

- Read a book with a Black main character and write a review about it.

- Do you think civil disobedience is ever okay?

- How has life for Black Americans changed in the last 10 years? 15 years? 30 years?

- Pick a historical park or monument that commemorates Black history, and write a few paragraphs about its significance.

- Who is one prominent figure in Black history that you think everyone should know about?

- Click here and read about an important person in Black history. What are some ways their impact can be seen today?

- Why was February chosen for Black History Month?

- Who is your favorite Black author? Why?

- Besides Black History Month, is one way that the U.S. celebrates Black history?

- Who do you think is the most influential person in Black history? Why?

What’s Next?

If you enjoyed these writing prompts and want to try more, we’ve got you covered!

We also have resources for teachers and parents, covering a multitude of subjects.

If you are looking for a particular subject and can’t find it, let us know – there’s every chance we’ll be inspired to create what you’re looking for!

We’d love to hear from you.

How to Tell 400 Years of Black History in One Book

From 1619 to 2019, this collection of essays, edited by two of the nation’s preeminent scholars, shows the depth and breadth of African American history

History Correspondent

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/31/de/31deb99d-0dcc-43eb-b801-171fb1aec4bc/gettyimages-515185532.jpg)

In August of 1619, the English warship White Lion sailed into Hampton Roads, Virginia, where the conjunction of the James, Elizabeth and York rivers meet the Atlantic Ocean. The White Lion ’s captain and crew were privateers, and they had taken captives from a Dutch slave ship. They exchanged, for supplies, more than 20 African people with the leadership and settlers at the Jamestown colony. In 2019 this event, while not the first arrival of Africans or the first incidence of slavery in North America , was widely recognized as inaugurating race-based slavery in the British colonies that would become the United States.

That 400th anniversary is the occasion for a unique collaboration: Four Hundred Souls: A Community History of African America, 1619-2019 , edited by historians Ibram X. Kendi and Keisha N. Blain. Kendi and Blain brought together 90 black writers—historians, scholars of other fields, journalists, activists and poets—to cover the full sweep and extraordinary diversity of those 400 years of black history. Although its scope is encyclopedic, the book is anything but a dry, dispassionate march through history. It’s elegantly structured in ten 40-year sections composed of eight essays (each covering one theme in a five-year period) and a poem punctuating the section conclusion; Kendi calls Four Hundred Souls “a chorus.”

The book opens with an essay by Nikole Hannah-Jones, the journalist behind the New York Times ’ 1619 Project , on the years 1619-1624, and closes with an entry from Black Lives Matter co-creator Alicia Garza writing about 2014-19, when the movement rose to the forefront of American politics. The depth and breadth of the material astounds, between fresh voices, such as historisn Mary Hicks writing about the Middle Passage for 1694-1699, and internationally renowned scholars, such as Annette Gordon-Reed writing about Sally Hemings for 1789-94. Prominent journalists include, in addition to Hannah-Jones, The Atlantic ’s Adam Serwer on Frederick Douglass (1859-64) and New York Times columnist Jamelle Bouie on the Civil War (1864-69). The powerful poems resonate sharply with the essays, Chet’la Sebree’s verses in “And the Record Repeats” about the experiences of young black women, for example, and Salamishah M. Tillet’s account of Anita Hill’s testimony in the Senate confirmation hearings for Supreme Court Justice Clarence Thomas.

“We are,” Kendi writes in the introduction collectively of black Americans, “reconstructing ourselves in this book.” The book itself, Blain writes in the conclusion, is “a testament to how much we have overcome, and how we have managed to do it together, despite our differences and diverse perspectives.” In an interview, Blain talked about how the project and the book’s distinctive structure developed, and how the editors imagine it will fit into the canon of black history and thought. A condensed and edited version of her conversation with Smithsonian is below.

Four Hundred Souls: A Community History of African America, 1619-2019

Four Hundred Souls is a unique one-volume “community” history of African Americans. The editors, Ibram X. Kendi and Keisha N. Blain, have assembled 90 brilliant writers, each of whom takes on a five-year period of that four-hundred-year span.

How did the Four Hundred Souls book come about?

We started working on the project in 2018 (it actually predates the [publication of] the New York Times 1619 Project.) Ibram reached out to me with the idea that with the 400th year anniversary of the first captive Africans arriving in Jamestown, maybe we should collaborate on a project that would commemorate this particular moment in history, and look at 400 years of African American history by pulling together a diverse set of voices.

The idea was that we'd be able to create something very different than any other book on black history. And as historians, we were thinking, what would historians of the future want? Who are the voices they would want to hear from? We wanted to create something that would actually function as a primary source in another, who knows, 40 years or so—that captures the voices of black writers and thinkers from a wide array of fields, reflecting on both the past but also the present too.

Did you have any models for how you pulled all these voices together?

There are a couple of models in the sense of the most significant, pioneering books in African American history. We thought immediately of W.E.B. De Bois' Black Reconstruction in America in terms of the scope of the work, the depth of the content, and the richness of the ideas. Robin D.G. Kelley's Freedom Dreams is another model, but more recent. Martha Jones' Vanguard , is a book that captures decades right of black women's political activism and the struggle for the vote in a way that I think, does a similar kind of broad, sweeping history. Daina Ramey Berry and Kali N. Gross's Black Woman's History of the United States is another.

But ours was not a single authored book or even an edited collection of just historians. We didn't want to produce a textbook, or an encyclopedia. We wanted this work to be, as an edited volume, rich enough and big enough to cover 400 years of history in a way that would keep the reader engaged from start to finish, 1619 to 2019. That’s part of the importance of the multiple different genres and different voices we included moving from period to period.

How does Four Hundred Souls reflect the concept of a community history?

We figured that community would show up in different ways in the narrative, but we were really thinking initially, how do we recreate community in putting this book together? One of the earliest analogies that Ibram used was describing this as a choir. I love this—he described the poets as soloists. And then in this choir, you'd have sopranos, you'd have tenors, and you’d have altos. And so the question was: Who do we invite to be in this volume that would capture collectively that spirit of community?

We recognized that we could never fully represent every single field and every single background, but we tried as much as possible. And so even in putting together the book, there was a moment where we said, for example, "Wait a minute, we don't really have a scholar here who would be able to truly grapple with the sort of interconnection between African American History and Native American history." So we thought, is there a scholar, who identifies as African American and Native American and then we reached out to [UCLA historian] Kyle Mays .

So there were moments where we just had to be intentional about making sure that we were having voices that represented as much as possible the diversity of black America. We invited Esther Armah to write about the black immigrant experience because what is black America without immigrants? The heart of black America is that it's not homogenous at all—it's diverse. And we tried to capture that.

We also wanted to make sure that a significant number of the writers were women, largely because we acknowledge that so many of the histories that we teach, that we read, and that so many people cite are written by men. There's still a general tendency to look for male expertise, to acknowledge men as experts, especially in the field of history. Women are often sidelined in these conversations . So we were intentional about that, too, and including someone like Alicia Garza, one of the founders of Black Lives Matter, we wanted to acknowledge the crucial role that black women are playing in shaping American politics to this very day.

How did historians approach their subjects differently than say, creative writers?

One of the challenges with the book, which turned out to be also an opportunity, was that we were focusing on key historical moments, figures, themes and places in the United States, each within in a very specific five-year period. We actually spent a lot of time mapping out instructions for authors. It wasn't just: “Write a piece for us on this topic.” We said, “Here's what we want and what we don't want. Here's what we expect of you ask these questions as you're writing the essay, make sure you're grappling with these particular themes.”

But they also had to have a bit of freedom, to look backward, and also to look forward. And I think the structure with a bit of freedom worked, it was a pretty nice balance. Some essays the five years just fit like a glove, others a little less so but the writers managed to pull it off.

We also spent a lot of time planning and carefully identifying who would write on certain topics. “Cotton,” which memoirist Kiese Laymon wrote about for 1804-1809, is a perfect example. We realized very early that if we asked a historian to write about cotton, they would be very frustrated with the five-year constraint. But when we asked Kiese, we let him know that we would provide him with books on cotton and slavery for him to take a look at. And then he brought to it his own personal experience, which turned out to be such a powerful narrative. He writes, “When the land is freed, so will be all the cotton and all the money made off the suffering that white folks made cotton bring to Black folks in Mississippi and the entire South.”

And so that's the other element of this too. Even a lot of people wondered how we would have a work of history with so many non-historians. We gave them clear guidance and materials, and they brought incredible talent to the project.

The New York Times ’ 1619 project shares a similar point of origin, the 400th anniversary of the arrival of enslaved Africans to colonial America. What did you make of it when it came out last year?

When the 1619 Project came out, [Ibram and I] were thrilled, because actually, it, in so many ways, complemented our vision for our project. Then we decided we really had to invite Nikole Hannah-Jones to contribute. We weren't sure who we would ask for that first essay, but then we were like, "You know what? This makes sense."

I know there are so many different critiques, but for me, what is most valuable about the project is the way that it demonstrates how much, from the very beginning, the ideas and experiences of black people have been sidelined.

This is why we wanted her to write her essay [about the slave ship White Lion .] Even as someone who studied U.S. history, I did not even know about the White Lion for many years. I mean, that's how sad it is…but I could talk about the Mayflower . That was part of the history that I was taught. And so what does that tell us?

We don't talk about 1619 the way that we do 1620. And why is that? Well, let's get to the heart of the matter. Race matters and racism, too, in the way that we even tell our histories. And so we wanted to send that message. And like I said, to have a complementary spirit and vision as the 1619 Project.

When readers have finished going through 400 Souls , where else can they read black scholars writing on black history?

One of the things that the African American Intellectual History Society [Blain is currently president of the organization] is committed to doing is elevating the scholarship and writing of Black scholars as well as a diverse group of scholars who work in the field of Black history, and specifically Black intellectual history.

Black Perspectives [an AAIHS publication] has a broad readership, certainly, we're reaching academics in the fields of history and many other fields. At the same time, a significant percentage of our readers are non-academics. We have activists who read the blog, well known intellectuals and thinkers, and just everyday lay people who are interested in history, who want to learn more about black history and find the content accessible.

Get the latest History stories in your inbox?

Click to visit our Privacy Statement .

A Note to our Readers Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.

Karin Wulf | | READ MORE

Karin Wulf is the director of the John Carter Brown Library and a historian at Brown University. She was previously the executive director of the Omohundro Institute of American History & Culture and a professor of history at William & Mary.

Black History Month Writing Prompts for Students

Let’s celebrate Black History Month! As educators, parents, and mentors, we understand the importance of fostering a sense of pride, knowledge, and cultural awareness in the hearts and minds of our students.

We’ve compiled a collection of engaging Black History Month writing prompts for students.

These writing prompts are designed to spark curiosity, encourage reflection, and inspire young minds to explore the rich tapestry of African American history.

Check out our top list of Black History Month writing prompts for students. This list features excellent writing prompts suitable for Kindergarten, elementary school , and middle school students . Let’s get writing!

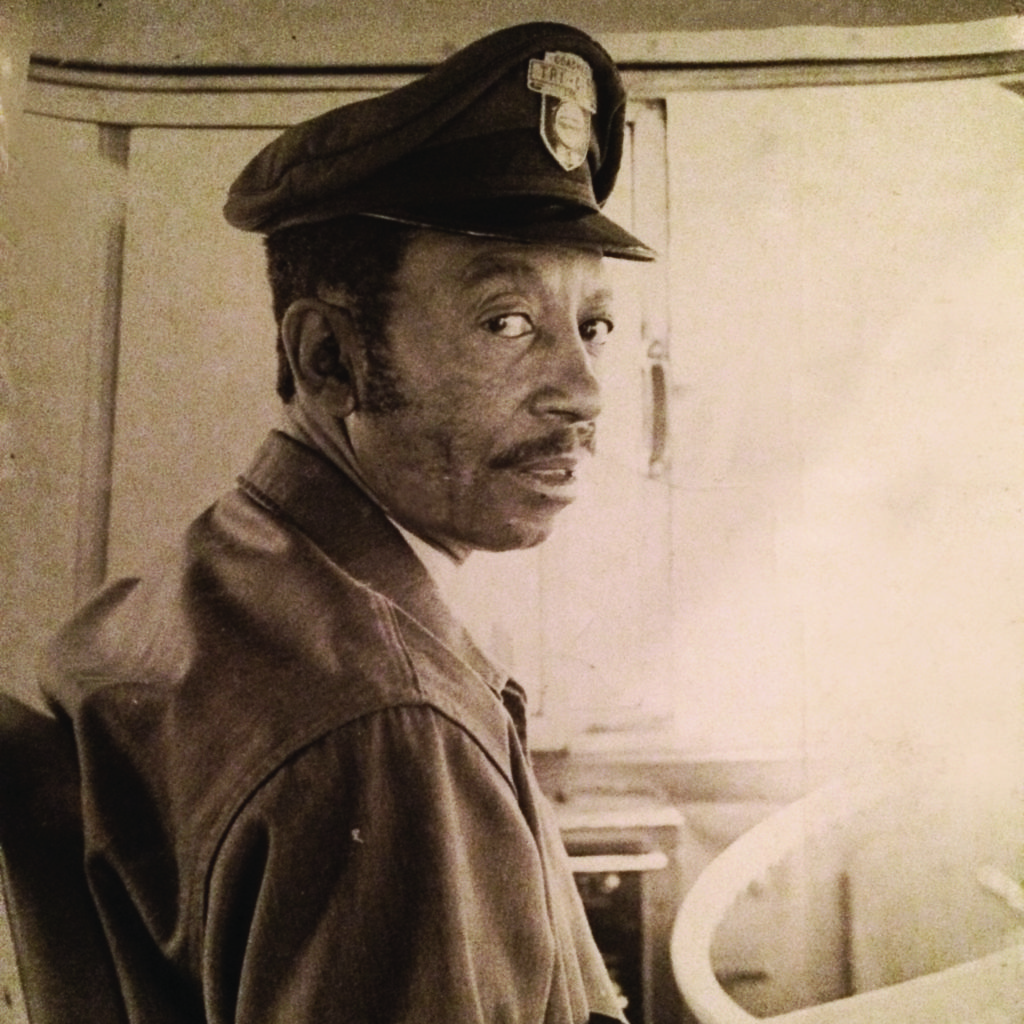

No one has played a greater role in helping all Americans know the black past than Carter G. Woodson, the individual who created Negro History Week in Washington, D.C., in February 1926. Woodson was the second black American to receive a PhD in history from Harvard—following W.E.B. Du Bois by a few years. To Woodson, the black experience was too important simply to be left to a small group of academics. Woodson believed that his role was to use black history and culture as a weapon in the struggle for racial uplift. By 1916, Woodson had moved to DC and established the “Association for the Study of Negro Life and Culture,” an organization whose goal was to make black history accessible to a wider audience. Woodson was a strange and driven man whose only passion was history, and he expected everyone to share his passion.

Dr. Carter G. Woodson, late 1940s

This impatience led Woodson to create Negro History Week in 1926, to ensure that school children be exposed to black history. Woodson chose the second week of February in order to celebrate the birthday of Lincoln and Frederick Douglass. It is important to realize that Negro History Week was not born in a vacuum. The 1920s saw the rise in interest in African American culture that was represented by the Harlem Renaissance where writers like Langston Hughes, Georgia Douglass Johnson, Claude McKay—wrote about the joys and sorrows of blackness, and musicians like Louie Armstrong, Duke Ellington, and Jimmy Lunceford captured the new rhythms of the cities created in part by the thousands of southern blacks who migrated to urban centers like Chicago. And artists like Aaron Douglass, Richmond Barthé, and Lois Jones created images that celebrated blackness and provided more positive images of the African American experience.

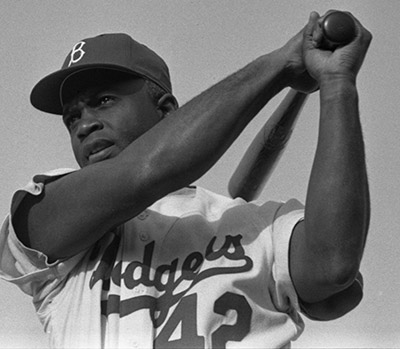

Woodson hoped to build upon this creativity and further stimulate interest through Negro History Week. Woodson had two goals. One was to use history to prove to white America that blacks had played important roles in the creation of America and thereby deserve to be treated equally as citizens. In essence, Woodson—by celebrating heroic black figures—be they inventors, entertainers, or soldiers—hoped to prove our worth, and by proving our worth—he believed that equality would soon follow. His other goal was to increase the visibility of black life and history, at a time when few newspapers, books, and universities took notice of the black community, except to dwell upon the negative. Ultimately Woodson believed Negro History Week—which became Black History Month in 1976—would be a vehicle for racial transformation forever.

The question that faces us today is whether or not Black History Month is still relevant? Is it still a vehicle for change? Or has it simply become one more school assignment that has limited meaning for children. Has Black History Month become a time when television and the media stack their black material? Or is it a useful concept whose goals have been achieved? After all, few—except the most ardent rednecks - could deny the presence and importance of African Americans to American society or as my then-14 year old daughter Sarah put it, “I see Colin Powell everyday on TV, all my friends—black and white—are immersed in black culture through music and television. And America has changed dramatically since 1926—Is not it time to retire Black History Month as we have eliminated white and colored signs on drinking fountains?” I will spare you the three hour lesson I gave her.

I would like to suggest that despite the profound change in race relations that has occurred in our lives, Carter G. Woodson’s vision for black history as a means of transformation and change is still quite relevant and quite useful. African American history month, with a bit of tweaking, is still a beacon of change and hope that is still surely needed in this world. The chains of slavery are gone—but we are all not yet free. The great diversity within the black community needs the glue of the African American past to remind us of not just how far we have traveled but lo, how far there is to go.

While there are many reasons and examples that I could point towards, let me raise five concerns or challenges that African Americans — in fact — all Americans — face that black history can help address:

The Challenge of Forgetting

You can tell a great deal about a country and a people by what they deem important enough to remember, to create moments for — what they put in their museum and what they celebrate. In Scandinavia — there are monuments to the Vikings as a symbol of freedom and the spirit of exploration. In Germany during the 1930s and 1940s, the Nazis celebrated their supposed Aryan supremacy through monument and song. While America traditionally revels in either Civil War battles or founding fathers. Yet I would suggest that we learn even more about a country by what it chooses to forget — its mistakes, its disappointments, and its embarrassments. In some ways, African American History month is a clarion call to remember. Yet it is a call that is often unheeded.

Let’s take the example of one of the great unmentionable in American history — slavery. For nearly 250 years slavery not only existed but it was one of the dominant forces in American life. Political clout and economic fortune depended on the labor of slaves. And the presence of this peculiar institution generated an array of books, publications, and stories that demonstrate how deeply it touched America. And while we can discuss basic information such as the fact that in 1860 — 4 million blacks were enslaved, and that a prime field hand cost $1,000, while a female, with her childbearing capability, brought $1,500, we find few moments to discuss the impact, legacy, and contemporary meaning of slavery.

In 1988, the Smithsonian Institution, about to open an exhibition that included slavery, decided to survey 10,000 Americans. The results were fascinating — 92% of white respondents felt slavery had little meaning to them — these respondents often said “my family did not arrive until after the end of slavery.” Even more disturbing was the fact that 79% of African Americans expressed no interest or some embarrassment about slavery. It is my hope that with greater focus and collaboration Black History Month can stimulate discussion about a subject that both divides and embarrasses.

As a historian, I have always felt that slavery is an African American success story because we found ways to survive, to preserve our culture and our families. Slavery is also ripe with heroes, such as slaves who ran away or rebelled, like Harriet Tubman or Denmark Vessey, but equally important are the forgotten slave fathers and mothers who raised families and kept a people alive. I am not embarrassed by my slave ancestors; I am in awe of their strength and their humanity. I would love to see the African American community rethink its connection to our slave past. I also think of something told to me by a Mr. Johnson, who was a former sharecropper I interviewed in Georgetown, SC:

Though the slaves were bought, they were also brave. Though they were sold, they were also strong.

The Challenge of Preserving a People’s Culture

While the African American community is no longer invisible, I am unsure that as a community we are taking the appropriate steps to ensure the preservation of African American cultural patrimony in appropriate institutions. Whether we like it or not, museums, archives, and libraries not only preserves culture they legitimize it. Therefore, it is incumbent of African Americans to work with cultural institutions to preserve their family photography, documents, and objects. While African Americans have few traditions of giving material to museums, it is crucial that more of the black past make it into American cultural repositories.

A good example is the Smithsonian, when the National Museum of American History wanted to mount an exhibition on slavery, it found it did not have any objects that described slavery. That is partially a response to a lack of giving by the African American Community. This lack of involvement also affects the preservation of black historic sites. Though there has been more attention paid to these sites, too much of our history has been paved over, gone through urban renewal, gentrified, or unidentified, or un-acknowledged. Hopefully a renewed Black History Month can focus attention on the importance of preserving African American culture.

There is no more powerful force than a people steeped in their history. And there is no higher cause than honoring our struggle and ancestors by remembering.

The Challenge of Maintaining a Community

As the African American Community diversifies and splinters, it is crucial to find mechanisms and opportunities to maintain our sense of community. As some families lose the connection with their southern roots, it is imperative that we understand our common heritage and history. The communal nature of black life has provided substance, guidance, and comfort for generations. And though our communities are quite diverse, it is our common heritage that continues to hold us together.

The Power of Inspiration

One thing has not changed. That is the need to draw inspiration and guidance from the past. And through that inspiration, people will find tools and paths that will help them live their lives. Who could not help but be inspired by Martin Luther King’s oratory, commitment to racial justice, and his ultimate sacrifice. Or by the arguments of William and Ellen Craft or Henry “Box” Brown who used great guile to escape from slavery. Who could not draw substance from the creativity of Madame CJ Walker or the audacity and courage of prize fighter Jack Johnson. Or who could not continue to struggle after listening to the mother of Emmitt Till share her story of sadness and perseverance. I know that when life is tough, I take solace in the poetry of Paul Lawrence Dunbar, Langston Hughes, Nikki Giovanni, or Gwendolyn Brooks. And I find comfort in the rhythms of Louie Armstrong, Sam Cooke or Dinah Washington. And I draw inspiration from the anonymous slave who persevered so that the culture could continue.

Let me conclude by re-emphasizing that Black History Month continues to serve us well. In part because Woodson’s creation is as much about today as it is about the past. Experiencing Black History Month every year reminds us that history is not dead or distant from our lives.

Rather, I see the African American past in the way my daughter’s laugh reminds me of my grandmother. I experience the African American past when I think of my grandfather choosing to leave the South rather than continue to experience share cropping and segregation. Or when I remember sitting in the back yard listening to old men tell stories. Ultimately, African American History — and its celebration throughout February — is just as vibrant today as it was when Woodson created it 85 years ago. Because it helps us to remember there is no more powerful force than a people steeped in their history. And there is no higher cause than honoring our struggle and ancestors by remembering.

Lonnie Bunch Founding Director

Subtitle here for the credits modal.

How Negro History Week Became Black History Month and Why It Matters Now

By Veronica Chambers and Jamiel Law Feb. 24, 2021

- Share full article

Black History Month has been celebrated in the United States for close to 100 years. But what is it, exactly, and how did it begin?

In the years after Reconstruction, campaigning for the importance of Black history and doing the scholarly work of creating the canon was a cornerstone of civil rights work for leaders like Carter G. Woodson. Martha Jones, a professor of history at Johns Hopkins University and the Society of Black Alumni Presidential Professor, explained: “These are men [like Woodson] who were trained formally and credentialed in the ways that all intellectuals and thought leaders of the early 20th century were trained at Harvard and places like that. But in order to make the argument, in order to make the claim about Black genius, about Black excellence, you have to build the space in which to do that. There is no room.” This is how they built the room.

On Feb. 20, Frederick Douglass, the most powerful civil rights advocate of his era, dies.

Douglass collapsed after attending a meeting with suffragists, including his friend Susan B. Anthony. A lifelong supporter of women’s rights, Douglass was among the 32 men who signed the Declaration of Sentiments at Seneca Falls, N.Y. He once said: “When I ran away from slavery, it was for myself; when I advocated emancipation, it was for my people. But when I stood up for the rights of woman, self was out of the question, and I found a little nobility in the act.”

Douglass was such an animated storyteller that, when he collapsed, his wife thought it was part of the story he was telling her about his day with the suffragists.

Washington, D.C., schools begin to celebrate what becomes known as Douglass Day.