The Freedom Charter in South Africa

Document Calls for Equality, Freedom, and Justice

B. Bahr / Getty Images

- American History

- African American History

- Ancient History and Culture

- Asian History

- European History

- Latin American History

- Medieval & Renaissance History

- Military History

- The 20th Century

- Women's History

- Postgraduate Certificate in Education, University College London

- M.S., Imperial College London

- B.S., Heriot-Watt University

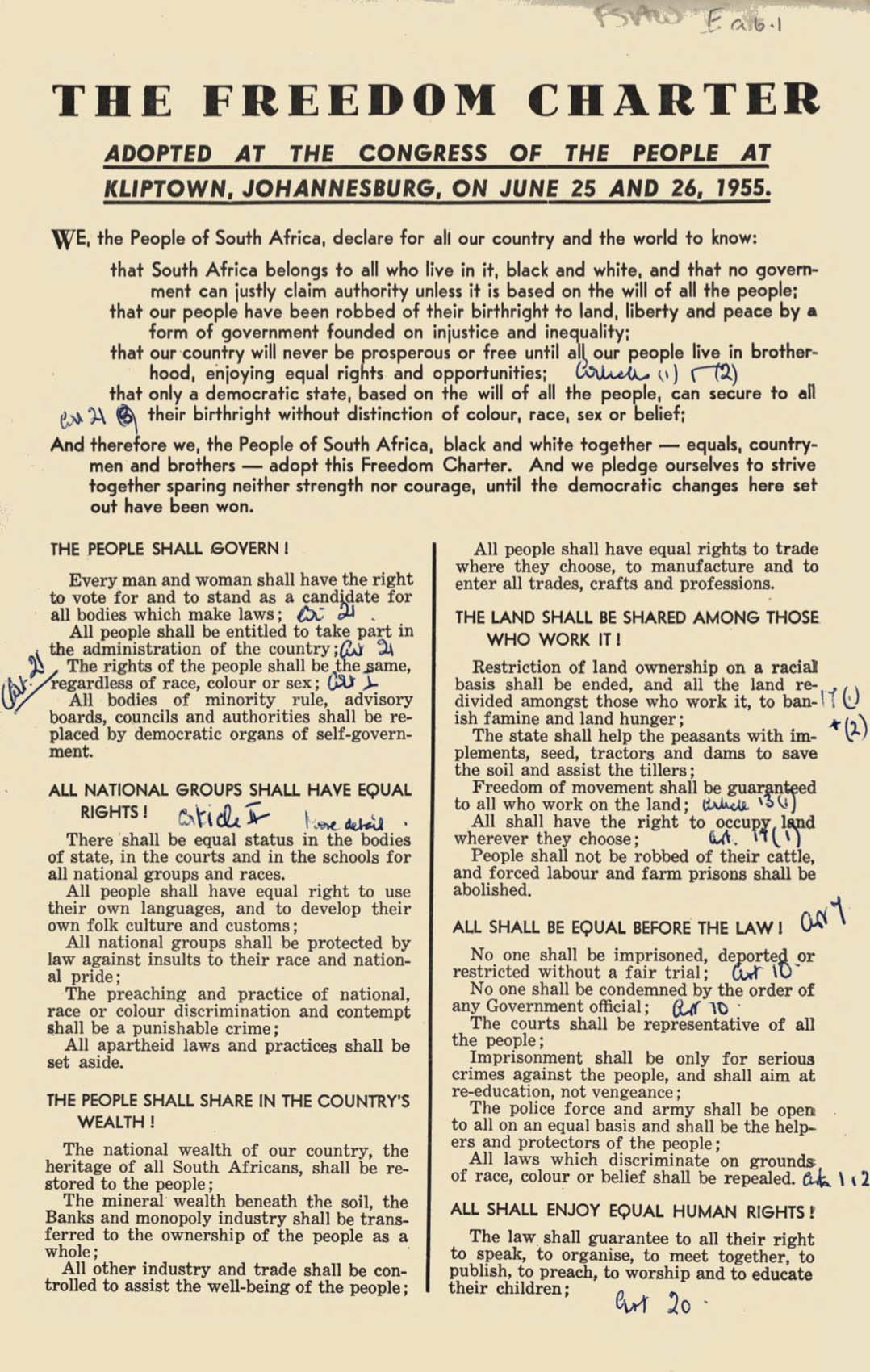

The Freedom Charter was a document ratified at the Congress of the People held at Kliptown, Soweto , South Africa in June 1955 by the various member bodies of the Congress Alliance. The policies set out in the Charter included a demand for a multi-racial, democratically elected government, equal opportunities, the nationalization of banks, mines, and heavy industries, and a redistribution of land. Africanist members of the ANC rejected the Freedom Charter and broke away to form the Pan Africanist Congress.

In 1956, following extensive searches of various homes and confiscation of documents, 156 people involved in the creation and ratification of the Freedom Charter were arrested for treason. This was almost the entire executive of the African National Congress (ANC), Congress of Democrats, South African Indian Congress, Coloured People's Congress, and the South African Congress of Trade Unions (collectively known as the Congress Alliance). They were charged with " high treason and a countrywide conspiracy to use violence to overthrow the present government and replace it with a communist state. " The punishment for high treason was death.

The Freedom Charter and Clauses

"We, the People of South Africa, declare for all our country and the world to know that South Africa belongs to all who live in it, black and white, and that no government can justly claim authority unless it is based on the will of all the people." -The Freedom Charter

Here is a synopsis of each of the clauses, which list various rights and stances in detail.

- The People Shall Govern : This point included universal voting rights and the rights to run for office and serve on governing boards regardless of race, color, and sex.

- All National Groups Shall Have Equal Rights : Apartheid laws will be set aside, and all groups will be able to use their own language and customs without discrimination.

- The People Shall Share in the Country's Wealth : Minerals, banks, and monopoly industries would become government-owned for the good of the people. All would be free to ply any trade or profession, but industry and trade would be controlled for the well-being of the whole people.

- The Land Shall Be Shared Among Those Who Work It: There will be land redistribution with assistance to peasants to farm it and an end to racial restrictions on ownership and freedom of movement.

- All Shall Be Equal Before the Law : This gives people rights to a fair trial, representative courts, fair imprisonment, as well as integrated law enforcement and military. There will be no discrimination by law for race, color, or beliefs.

- All Shall Enjoy Equal Human Rights : People are granted the freedom of speech, assembly, the press, religion, and education. This addresses protection from police raids, freedom to travel, and abolishment of pass laws.

- There Shall Be Work and Security : There will be equal pay for equal work for all races and genders. People have the right to form unions. There were workplace rules adopted including a 40-hour work week, unemployment benefits, minimum wage, and leave. This clause eliminated child labor and other abusive forms of labor.

- The Doors of Learning and Culture Shall Be Opened : This clause addresses free education, access to higher education, ending adult illiteracy, promoting culture, and ending cultural color bans.

- There Shall Be Houses, Security and Comfort : This gives the right to decent, affordable housing, free medical care and preventive health, care of the aged, orphans, and disabled.

- Rest, Leisure and Recreation Shall Be the Right of All.

- There Shall Be Peace and Friendship : This clause says we should strive for world peace by negotiation and recognition of rights to self-government.

The Treason Trial

At the treason trial in August, 1958, the prosecution attempted to show that the Freedom Charter was a Communist tract and that the only way it could be achieved was by overthrowing the present government. However, the Crown's expert witness on Communism admitted that the Charter was " a humanitarian document that might well represent the natural reaction and aspirations of non-whites to the harsh conditions in South Africa. "

The main piece of evidence against the accused was a recording of a speech made by Robert Resha, the Trasvaal Volunteer-in-Chief, which appeared to say that volunteers should be violent when called upon to use violence. During the defense, it was shown that Resha's viewpoints were the exception rather than the rule in the ANC and that the short quote had been taken completely out of context.

The Outcome of the Treason Trial

Within a week of the trail starting, one of the two charges under the Suppression of Communism Act was dropped. Two months later the Crown announced that the whole indictment was being dropped, only to issue a new indictment against 30 people—all members of the ANC.

Chief Albert Luthuli and Oliver Tambo were released for lack of evidence. Nelson Mandela and Walter Sisulu (ANC secretary-general) were among the final 30 accused.

On March 29, 1961, Justice FL Rumpff interrupted the defense summation with a verdict. He announced that although the ANC was working to replace the government and had used illegal means of protest during the Defiance Campaign, the Crown had failed to show that the ANC was using violence to overthrow the government, and were therefore not guilty of treason. The Crown had failed to establish any revolutionary intent behind the defendant's actions. Having been found non-guilty, the remaining 30 accused were discharged.

The Ramifications of the Treason Trial

The Treason Trial was a serious blow to the ANC and the other members of the Congress Alliance. Their leadership was imprisoned or banned and considerable costs were incurred. Most significantly, the more radical members of the ANC's Youth League rebelled against the ANC interaction with other races and left to form the PAC.

Nelson Mandela, Walter Sisulu, and six others were eventually given a life sentence for treason in 1964 at what is known as the Rivonia Trial.

- Biography: Joe Slovo

- Biography of Walter Max Ulyate Sisulu, Anti-Apartheid Activist

- Biography of Nontsikelelo Albertina Sisulu, South African Activist

- Nelson Mandela

- What Was Apartheid in South Africa?

- Women's Anti-Pass Law Campaigns in South Africa

- South Africa's National Holidays

- The End of South African Apartheid

- Geography and History of South Africa

- The Origins of Apartheid in South Africa

- Chief Albert Luthuli

- Understanding South Africa's Apartheid Era

- The Christiana Riot

- Biography of Martin Thembisile (Chris) Hani, South African Activist

- What Are Civil Rights? Definition and Examples

- What Is Treason?

- Facebook Icon

- Twitter Icon

South Africa’s Freedom Charter Was a Landmark in the Global Struggle Against Racism

- Back Issues

“Religion,” our new issue, is out now. Subscribe to our print edition today.

The ANC’s Freedom Charter guided the struggle against white supremacy in South Africa, linking the questions of political and economic freedom. The origins of the charter — and the uses to which it was put — are rich with lessons for anti-racist struggles today.

The Freedom Charter was notable precisely for its insistence that economic and political rights were equally important. (Eli Weinberg / UWC Robben Island Mayibuye Archives)

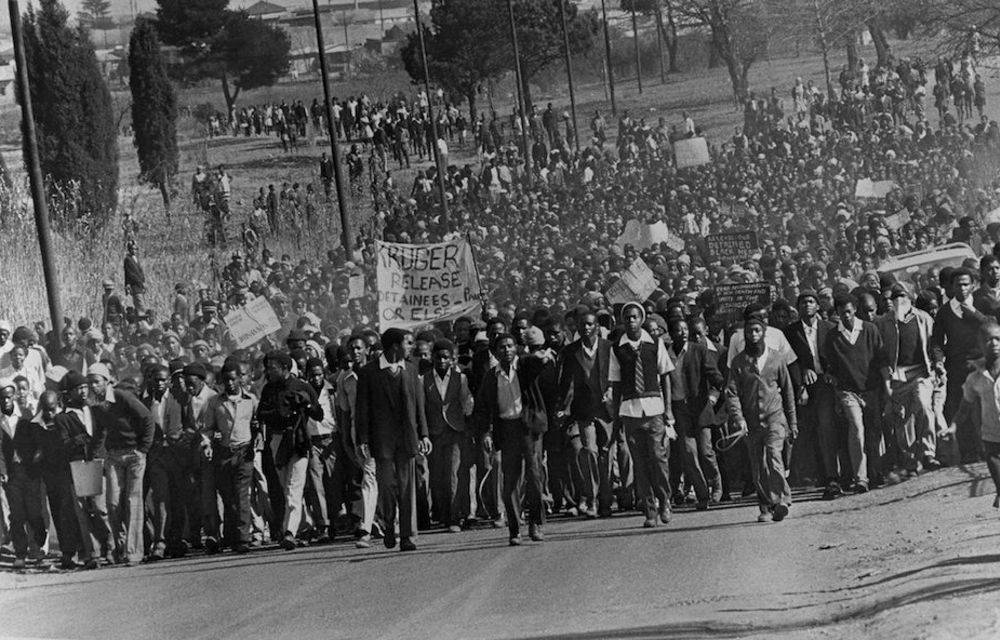

In June 1955, one of the most important events in the history of the South African freedom struggle took place. The Congress of the People assembled in a shabby field in Kliptown, a suburb of what would later be called Soweto. The main purpose of the event was to debate and ratify a “ Freedom Charter ” — a statement to the world about the character of a future South Africa freed from the shackles of white supremacy.

The document has obvious significance as the creed of the African National Congress (ANC), one of the most important liberation movements of the twentieth century. But the Freedom Charter also offers important philosophical and strategic insights for everyone on the left.

Influenced by the ideas of the liberal Enlightenment, the charter nevertheless transcends liberalism in crucial ways. Insisting on freedom, equality, and universal rights, the document is nevertheless quite specific — just where liberalism is abstract and evasive — about the material conditions that would be needed to make these rights meaningful.

The Roots of Apartheid

The Freedom Charter came at a particular time in South African history and its composition reflects that. Conventional wisdom often presents the system of white supremacy and black dispossession that characterized South Africa in the last century as a unique perversion dreamed up by Afrikaners, the white, Afrikaans-speaking population of the country (Afrikaans being a Dutch creole spoken by various groups in South Africa).

In fact, the various British-linked administrations that governed the country in the first half of the twentieth century had already established most of the tenets of the system that became known as apartheid. They had stripped blacks of the right to vote, to own land outside of tiny impoverished reserves, and to live in towns without a specific job-related accreditation called a “pass.”

All of this had an economic underpinning. In a rough-and-ready way, the racist history of twentieth-century South Africa can be understood as a compromise between different branches of white capital. Big capital, associated with the English-speaking white population, wanted sufficient black labor to work in the towns, and above all in the gold mines and other industries around Johannesburg. Afrikaner landowners wanted black farm laborers to be plentiful and cheap.

The arrival of the National Party with its Afrikaner support base and its rise to power in 1948 did not alter these underlying forces. However, there were changes. The formal system of apartheid ushered in a vast scheme of positive discrimination for white Afrikaans-speakers, triggering an influx of the barely educated white rural poor into reserved government jobs.

There was a graphic illustration of this trend during the Rivonia Trial, when Nelson Mandela and his comrades were in the dock, accused of treason. Prison guards who had benefitted from this affirmative-action program began to ask Mandela and his fellow detainees for help writing the essays they needed to submit in order to progress through the ranks of the service.

A Break With Liberalism

More importantly, the new regime — most of whose leaders had supported the Nazis during the Second World War — had no commitment to the vestiges of liberalism that earlier administrations had allowed, especially when it came to political expression and the separation of powers.

The Communist Party of South Africa was one of the first to bear the brunt of this repressive turn. While the party’s fortunes had waxed and waned since its founding in 1921, by the 1940s, it had a well-established multiracial membership, the majority of whom were black. In 1950, the Nationalist government brought in sweeping legislation to crush the Communist Party.

In a bid to frustrate this move, the party formally disbanded itself three days before the law was due to take effect. The decision to disband remains controversial to this day; in any case, it soon re-formed as an underground organization (now called the South African Communist Party or SACP).

The party’s formal dissolution accelerated trends that were already underway. Above all, it led to greater collaboration with the ANC and the Indian National Congress, two organizations that were by then the major vehicles for opposition to apartheid.

At the same time, the internal politics of the ANC itself were shifting. A new generation of leaders had grown impatient with the perceived gradualism and deference of the movement’s elders. For much of the 1940s, this tendency, centered on the ANC’s new Youth League, had an Africanist orientation. Writing in 1946, its chief ideologue Anton Lembede stated that “Africa is a black man’s country.”

Although Lembede was sympathetic to a vaguely defined form of socialism, he believed that a black African identity must be the fundamental axis of national liberation. He saw the proponents of non-racial collaboration and class struggle as enemies — at several points in the 1940s, Youth Leaguers attempted to have communists expelled from the ANC.

Lembede died in 1947, but his legacy lived on in the Youth League. His protégés included a triumvirate of new leaders who would change the course of South African history: Oliver Tambo, Walter Sisulu, and Nelson Mandela. It was the oldest of the three, Sisulu, who defined the next phase in ANC thinking. Sisulu had joined Lembede in pushing for the expulsion of communists from the congress in the 1940s. By the end of the decade, however, his views were changing.

One can adduce biographical reasons for this change: unlike Mandela or Tambo, Sisulu never went to university. He had pulled himself into the ranks of the black professional classes after a succession of manual jobs, including a stint working as a miner in the 1930s. As a miner, he came into contact with an earlier wave of radical trade unionism that organized black South Africans as workers.

Sisulu’s absent biological father was also white, although this did him no favors with the racist state. But his experience of ANC organizing in concert with Indian and white activists in the late 1940s appears to have been more important. Almost all of these activists — and an increasing number of ANC cadres — were communists. By the mid 1950s, Sisulu himself had also joined the party.

The defiance campaign, begun in 1952, was one of the fruits of this new thinking. It was a campaign of mass civil disobedience, where activists sought arrest by using facilities such as train carriages or counters specifically reserved for other races (most often for whites). The new approach combined a willingness to mobilize the masses in “impolite” forms of protest with an active embrace of cross-racial coalitions.

This turn also led to the formation of the Congress of Democrats — essentially the white branch of the Congress movement — and the Coloured Peoples’ Congress (“coloured” was the term used to describe the non-white, predominantly Afrikaans-speaking populations who are a majority in the Western Cape). This created an apparent paradox, not fully resolved until the 1990s, whereby the movement that led the opposition to apartheid reproduced the state’s own racial categories.

In 1954, representatives of all the Congress organizations met up to plan their next move. One delegate, Z. K. Matthews, proposed that a “congress of the people” be held, at which a “freedom charter” could be debated and ratified.

It was no accident that Matthews should have proposed this idea, with its echoes of England’s Magna Carta and the US Constitutional Convention. He was the head of Fort Hare, South Africa’s first black university, which counted both Mandela and Tambo amongst its alumni. Matthews was a stalwart of the movement, but also, in the words of Lionel “Rusty” Bernstein , “the most conventional, respectable, and thoroughly bourgeois activist…”

Underpinning what was to become the radicalism of the Freedom Charter, there was an ostensibly bourgeois, constitutionalist model of politics associated with figures like Matthews — harking back to an earlier era of ANC activism, one that partly sought to convince white interlocutors that a black elite, well versed in the heritage of “English liberty,” was ready for a share of power.

Working through the night, a committee cut this proposal down to manageable size. Its members included the up-and-coming Youth Leaguer Nelson Mandela, as well as the war veteran and communist architect Rusty Bernstein.

Matthews had suggested that the Congress should compile a non-racial voters’ roll. To compensate for dropping that idea, the committee added a crucial innovation: the charter would draw on “a nationwide campaign to persuade people everywhere to formulate their own proposals for the content of a Freedom Charter.”

The Congress of the People would also be open to delegates from any and all organizations. After the meeting, Bernstein drafted the call for submissions. Wrestling with the task, the slogan “let us speak of freedom” came to him, and with that, the rest of the call fell into place . An army of activists carried the message to thousands of meetings throughout the land.

Submissions drifted in, often written on the back of the same handbill as the original call, eventually numbering thousands of scraps of paper. Feeding and housing the Congress of the People delegates, while evading the state’s ever more intrusive agencies, was an organizational nightmare. The scraps were read briefly, then stuffed into a trunk while the organizers dealt with more pressing matters.

According to Bernstein, one of the problems was that “most of the ‘demands’ were not at all as we imagined them — at least not in the written form in which they reached us: most were one-liners dealing with a single issue of daily life, jobs, living standards, civil liberties.” In retrospect, however, this was a great strength.

Tangible Freedom

The document draws on the soaring rhetoric of the Enlightenment, particularly the US Declaration of Independence. However, freedom as defined in Kliptown was not abstract, but earthy and plebeian.

This applied even where the charter dealt with the “negative liberty” so often stressed by classical liberalism. It is hard to imagine the founding fathers defining freedom as the right not to have your cattle stolen, or not to be paid in cheap alcohol (the charter includes a reference to the notorious “dop” system that obliged workers in wine-growing regions to receive part of their wages in the latter form).

This concrete, popular definition of liberty contributed to an even more important aspect of the charter. Freedom cannot simply be formal: the principles of equality before the law, or one-man-one-vote, rely upon economic freedom to make them real. The charter insisted that health care, education, decent housing, nationalization of the mines and industrial monopolies, and a fair share of national wealth and of the land for those who work it were all just as essential to our liberty.

The liberal Enlightenment had posited an abstract and imaginary subject (“all men were created equal”). In contrast, the charter addressed real people living in a history that had created winners and losers. “Our people,” it told us, “have been robbed of their birth right.”

As Bernstein recalled, he dedicated most of his energy to distilling the comments of thousands of people into a set of clear themes, listed in the charter’s clauses. He then composed the more rhetorical preamble and conclusion quickly without much agonizing. Yet the preamble had immediate repercussions.

The statement that “South Africa belongs to all who live in it, black and white,” was by then the standard position of the ANC–Congress alliance. As James Moroka, then president of the ANC, and Walter Sisulu had written prior to the defiance campaign, their struggle was not “directed against any race or national group, but against unjust laws which keep in subjection and misery vast sections of the population.”

However, Bernstein’s succinct phrase, along with the charter’s general emphasis on a non-racial South Africa, inflamed Africanists within the ANC. It helped pave the way for the formation of the breakaway Pan Africanist Congress (PAC) in 1959. The PAC and its leader Robert Sobukwe argued that Africa was for (black) Africans. This emphasis of the charter on non-racialism also placed the Congress alliance at odds with many later forms of black radicalism, from Guinea’s Sékou Touré to Stokely Carmichael.

Toward the People

There is much that was accidental in the form that the charter took. Many of its most innovative features took shape as compromises, and the working party unsuccessfully tried to solicit input from a wider pool of white liberal and even conservative groups. However, the document and the Congress ultimately represented something that both the SACP and the ANC had been grasping toward throughout the 1940s and ’50s.

Both were centralized and relatively elitist organizations, with the ANC very clearly composed of a black elite — urban, educated, and often professional. The Communist Party did not come close to reflecting the makeup of the country either, even in urban areas. The 1940s had seen an impressive level of communist engagement in national campaigns, but with little input from the lower strata of the proletariat, a group that would surely be central to revolutionary change in a country like South Africa.

While activists had played a key role in events like the 1946 miners’ strike, the party had also watched cautiously from the sidelines as the urban poor organized a squatters’ movement that swept through Johannesburg in the 1940s. The defiance campaign, the Congress of the People, and the Freedom Charter sought to address this shortcoming.

It was the people who would provide the energy needed to win freedom, having first defined such freedom in their own terms. Within a few years, however, a combination of state repression and the leadership’s struggle to respond to such coercive pressure would drive the Congress alliance away from this new vision.

After the Congress of the People was over, the state brought charges of treason against 156 activists. The Freedom Charter was a central plank for the prosecution case. However, the move was premature, as the regime did not yet have the powers of repression it would later obtain, and the charges against the Congress activists — of plotting the violent overthrow of the state — were at this point clearly false. The state dropped most of the cases, and the remaining thirty defendants were acquitted in 1961.

The trial attracted large crowds and allowed the leadership of the movement to stay in contact for an extended period of time, something that repression and a lack of funds had previously made difficult. The police tried to avenge their failure to secure a conviction by raiding the home of Ruth First and Joe Slovo, trying to catch their black comrades celebrating with a glass in hand (it was then illegal to serve alcohol to black Africans).

But the screw was already tightening. In March 1960, police opened fire on an anti-pass demonstration in Sharpeville, killing sixty-nine people. After a moment of indecision, the state launched a further crackdown, suspending civil rights, rounding up of thousands of activists, and imposing a permanent ban on the ANC and PAC.

In the years that followed, the South African police formally received sweeping new powers of arrest and detention without trial. The ninety-day detention law, introduced in 1963, allowed the police to detain individuals in custody without trial for ninety days, then release and immediately re-arrest them.

The CIA gave police units training in torture techniques, and the use of solitary confinement became commonplace. Under these circumstances, many activists came to believe that the kind of non-violent mass politics attempted from the late 1940s onward, which had reached its apogee with the ratification of the Freedom Charter, was no longer viable.

The reasons for this are complex. While elders of the movement like ANC president Albert Luthuli were committed to Gandhian principles of non-violence, this had never been the position of Youth Leaguers like Sisulu or Mandela. They had been making discrete inquiries about the possibility of armed struggle from at least 1953.

While some writers have attributed this policy shift to a communist cabal or an overly romantic view of people’s war in countries like China and Algeria, this seems unlikely. ANC leaders appear to have been much more influenced by a fear that South Africa might go the same way as Kenya, where the anti-colonial Mau Mau insurgency had devolved into a bitter civil war, and by the mounting difficulty of resisting demands from the urban poor to “fight back” against the regime.

At the Rivonia Trial, Mandela spoke of the “inevitability” of African violence, and the need for “responsible leadership” to “canalize” this reaction in order to prevent outbreaks of “terrorism.”

Armed Struggle

In the face of such pressures, the ANC and the Communist Party both started to establish armed units. These units joined together to form Umkhonto we Sizwe (“the spear of the nation”), known as MK for short, with a High Command drawn from members of both organizations.

At first, MK launched a campaign of sabotage, keeping one foot in the mass politics of the 1950s. There were some successful operations, but overall, MK’s action caused little lasting damage or concern among South Africa’s rulers.

Instead of reconsidering its strategy, MK’s High Command began thinking about full-scale guerrilla war. With Mandela under arrest, and many other members in hiding, the High Command eventually authorized a military campaign called Operation Mayibuye (from the ANC slogan Mayibuye I Afrika , “come back Africa”).

The use of force against the evil of apartheid was surely justified on moral grounds. With hindsight, however, it seems to have been a strategic misreading of the situation. Although this is a conclusion that many people are reluctant to draw, because reactionaries branded the ANC as “terrorists,” it was in fact the view of numerous activists within the organization itself.

When a police sweep captured much of the leadership at Rivonia, Rusty Bernstein had been preparing to present his detailed objections to Operation Mayibuye, on the grounds that it “proceeded from a wholly inadequate analysis of the real balance of power in the country.” Many of the others captured, including Walter Sisulu, had similar misgivings.

Ahmed Kathrada, another of the Rivonia trialists convicted with Mandela, was more strenuously opposed to the military turn, and even to the campaign of sabotage as it had been undertaken, believing that “it would not be effective unless it was directly related to some mass campaign.”

Kathrada’s point implicitly draws attention to the gap in ANC thinking of the 1960s: between “disciplined” military strikes by small groups and non-violent mass campaigns there lay a third option, of a mass uprising that was neither militaristic nor based on Gandhian non-violence. The ANC did not give that option due attention.

The courts found those captured at Rivonia guilty, and they received life sentences. The only exceptions were Bob Hepple, who turned state’s evidence, then fled before testifying, Arthur Goldreich, who escaped before the trial with Harold Wolpe, and Rusty Bernstein, who was acquitted because of insufficient evidence, only to be immediately rearrested in court under the ninety-day law.

By sheer luck, the authorities granted Bernstein bail, allowing him to escape to Botswana (in true South African style, the Special Branch officer had been absent from the hearing because he was watching a rugby match).

A Popular Rebellion

In 1976, the Soweto uprising broke out. This rebellion, led by schoolchildren, had nothing to do with the ANC, which had mostly been absent from the country for over a decade. The ideology of the uprising — “Black Consciousness” — also had little in common with the non-racialism of the Freedom Charter, of which the young protesters were largely ignorant. As resistance grew, however, this changed.

By the 1980s, two organizations had emerged to spearhead a rebellious civil society: the revived trade union movement, eventually united under the umbrella of COSATU (Congress of South African Trade Unions), and a popular coalition of local groups known as the United Democratic Front (UDF). Both organizations had links to the ANC and its non-racialist ideology. The UDF formally adopted the Freedom Charter as its credo.

At the same time, the trade unions and the UDF were more democratic and less centralized than the ANC or SACP had ever been. It was they who rendered South Africa ungovernable in the late apartheid years, through their activism in the workplace and in the townships.

This rebellion posed a far more serious threat to apartheid than MK’s sporadic actions. It was this mass, popular Jacobinism, rather than MK’s rather insignificant military threat, that gave the ANC real leverage in the negotiations to end apartheid.

We should not romanticize these years. The uprising confirmed some of the forebodings enunciated by Nelson Mandela at Rivonia two decades earlier as thousands were killed. The apartheid state inflicted much of this violence, both directly and through its allies and proxies, most notably the Zulu nationalist Inkatha Freedom Party. But the “comrades” also made their own contribution.

The violent expulsion and killing of black police officers and municipal officials, and the dishing out of severe, often fatal forms of “people’s justice” against collaborators, both real and imagined, became commonplace.

As apartheid entered its endgame and the regime unbanned the ANC, several processes were apparent. First of all, the early 1990s were clearly not a propitious time to implement the social provisions of the Freedom Charter. Apartheid in its classic, mid-century phase had been about a shortage of black labor.

By now, however, mass unemployment was a crushing reality in most of the country, weakening the working class as a force for social justice. The collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991, and the ensuing free-market triumphalism of the Washington Consensus, also removed sources of support, whether material or ideological, for policies like mine nationalization or land reform.

Meanwhile, the internal politics of the ANC alliance pushed rightward. Just as the movement was on the brink of exercising power, an assassin gunned down SACP leader Chris Hani, a powerful voice from the left. His comrade Joe Slovo died of cancer not long afterward.

The anointing as Mandela’s successor of Thabo Mbeki, the son of an ANC veteran who had run Oliver Tambo’s office in London, symbolized a much wider displacement of those who had taken real risks during the rebellions of the 1980s, in favor of a “struggle bureaucracy” whose members now returned from exile.

As the ANC supplanted the UDF in the 1990s, sometimes appointing its more effective leaders to paid positions, it demobilized a federation of groups that could have effectively contested its drift to the right. In the absence of a radical economic program, the ANC drew on a kind of racialized neoliberalism, with a program of “Black Economic Empowerment” creating a class of black plutocrats while leaving the underlying disparities largely untouched.

COSATU fared somewhat better. It did have some positive influence on the government, in the earlier post-apartheid years at least — for example, by allying itself with the Treatment Action Campaign to make anti-retroviral HIV drugs available. But the unions have not done a good job of recruiting among the lowest-paid, informalized sections of the workforce, or of representing their interests.

This was graphically illustrated by the dispute at the platinum mines which triggered the Marikana massacre. The lowest-paid underground workers, rock drill operators, were in revolt against a pay scale negotiated by the National Union of Mineworkers (NUM) that left them behind . NUM officials were among those who had called for the military to be deployed against the strikers before the massacre.

Mythologizing the Struggle

South Africa’s post-apartheid rulers have implemented the provisions of the Freedom Charter that were consistent with liberalism, such as votes for all or equality before the law. However, the charter was notable precisely for its insistence that economic and political rights were equally important.

In a nod to this aspect, the new South African constitution did stipulate certain socio-economic rights — to health care services, sufficient food and water, and adequate social assistance. And the courts have sometimes forced the government to justify itself on such questions. In the absence of effective parliamentary scrutiny, this is important, but it has still done little to force the government’s hand.

There has been a real but comparatively small reduction in poverty since 1994, and there are now some important government programs. But income inequality has actually grown worse, with near-continuous economic growth since 1997 simply creating more wealth at the top. South Africa is generally considered to be the most unequal country in the world.

In today’s South Africa, people often mention the Freedom Charter, but its role in contemporary debate seems oddly divorced from its popular origins. The ANC now presents the charter, not as a demand for freedom dictated by the people themselves, but as a gift from the party. And this contributes to a wider liberation myth.

This myth erases the other forces that opposed apartheid: a memorial to Hector Pieterson, a martyr of Soweto’s school uprisings inspired by Black Consciousness, salutes him in the name of the ANC Youth League, and the UDF is either forgotten or evoked as a placeholder for the ANC in exile.

One consequence of this myth is to reinforce the notion of what we might term “struggle debt,” according to which the people owe the ANC a debt for their liberation. Rather like original sin, this is a debt that can never be redeemed, only forgiven through the grace of the party.

South Africa and the wider world urgently need to recover the true meaning of the Freedom Charter. It showed us that personal liberty cannot be separated from economic freedom, and that non-racialism must be connected to the radical redistribution of wealth. Needless to say, this stands in stark contrast to what has actually happened in the new South Africa, where the poor can vote while their children go hungry, and where “empowerment” means the creation of black billionaires to stand alongside the white ones.

Another key contribution of the charter was its use of freedom as an organizing concept for the Left. And here the method of the Freedom Charter, with the call for submissions through which it was assembled, is as important as what the text says. To actually ask ordinary people about “the things that will make us free,” to try and summarize their ideas while drawing upon their vocabularies, is a skill that the Left needs to rediscover. “Let us speak together of freedom!”

National Archives and Records Service of South Africa

Thirty years ago, the South African miracle came true. Millions voted in the country’s first democratic elections, seemingly delivering a death blow to apartheid.

The African National Congress rose to power under the leadership of Nelson Mandela and used the Freedom Charter, a decades-old manifesto, as a guide to forming a new nation.

The charter’s 10 declarations offered a vision for overcoming apartheid through a free, multiracial society, with quality housing, education and economic opportunities for all.

As South Africans celebrate 30 years of freedom and prepare to vote in a pivotal national election, we looked at how far the country has come in meeting the Freedom Charter’s goals.

Has South Africa Truly Defeated Apartheid?

By John Eligon and Lynsey Chutel in Johannesburg and Lauren Leatherby in London. Photographs by Joao Silva .

When the apartheid government was toppled in South Africa, ending white minority rule, people around the world shared in the excitement and optimism that a more just society would emerge. A generation later, the country’s journey provides a broader lesson: It is far easier to rally for an end to racism than it is to undo entrenched inequities and to govern a complicated country.

The African National Congress won the 1994 election on the promise of “a better life for all.” But for many that promise has fallen short. Polls now suggest that in the election scheduled for May 29, the party risks losing its absolute majority in the national government for the first time.

No one doubts that South Africa has made strides since the days of legalized racial oppression. Democracy has brought a growing Black middle class, access to better education across racial lines and a basic human dignity once stolen from the Black majority.

But there also has been a widening gap between rich and poor, a breakdown in basic services like electricity and water, and the continued isolation of Black families stuck in ramshackle homes in distant communities.

Black South Africans, who make up 81 percent of the population, often argue that they’ve gained political freedom, but not economic freedom — and remain trapped in the structure of apartheid.

We went through the Freedom Charter’s declarations — each ending in an exclamation point — to measure South Africa’s progress and shortcomings over the past 30 years.

100% turnout among voting-age population

Voter turnout has dropped.

U.S.A., 2020 - 63%

U.K., 2019 - 62%

U.S.A., 2020 – 63%

U.K., 2019 – 62%

Sources: Collette Schulz-Herzenberg, "The South African non-voter: An analysis"; Konrad Adenaur Stiftung, 2020 (South Africa); Pew Research (United States and U.K.)

On a continent where coups, autocrats and flawed elections have become common, South Africa is a widely admired exception.

Since 1994, the country has held national elections every five years, with local elections in between. Presidents have changed, but the party in power — the A.N.C. — never has. Despite this, there have never been any serious doubts about the integrity of those electoral contests. A record 52 parties will compete in the national election this year.

Despite the electoral stability, politics have been dangerous. Fierce conflict within the A.N.C. has resulted in many assassinations over the years. The A.N.C.’s access to state resources as the governing party has fueled many of the disputes and led to widespread corruption — from top national officials down to local councilors.

The enrichment of A.N.C. leaders while many people barely earn enough to feed themselves has shaken the faith of many South Africans in their democratic system.

Last year, 22 percent of South Africans approved of the functioning of the country’s democracy, down from 63 percent in 2004, according to surveys from the Human Sciences Research Council.

Under apartheid, race restricted every aspect of life for South Africans who were Black, Indian and colored — a multiracial classification created by the government. There were strict limits on where they could live, attend school, work and travel. Laws enforced this segregation, and partaking in politics was criminalized.

But the democratic government drafted a constitution that enshrined equal rights for all.

South Africa has become a place where people of all races often dine, worship and party together. Gay rights are largely accepted. There is a free and vigorous press, and protests and open political debate are a part of life.

But many of the economic barriers created under apartheid still endure.

By one measure, the World Bank has ranked South Africa as the most unequal country in the world. Ten percent of the population holds about 71 percent of the country’s wealth, while the bottom 60 percent holds just 7 percent of assets, according t o the World Bank .

To a large extent, the wealth disparities have kept millions of Black South Africans relegated to some of the most deplorable conditions.

Just look at the place in the Soweto community of Kliptown where hundreds of anti-apartheid activists gathered to draft the Freedom Charter in 1955. It is now known as Walter Sisulu Square, named for a prominent anti-apartheid activist.

Nearly two decades ago, the government built a large concrete complex around the square, with restaurants, offices and a hotel. But because of a lack of maintenance and huge riots in 2021 that stemmed from political grievances, most of the businesses are now gutted, littered and stinking of sewage. Informal traders eke out a living nearby selling sandwiches, clothes and fruit.

Across adjacent railroad tracks sits an all-Black neighborhood where most residents live in tin shacks, use outdoor latrines, rely on jury-rigged wires for electricity and navigate craggy dirt roads.

Walter Sisulu Square in Kliptown, Soweto, where South Africa’s Freedom Charter was signed in 1955, is now dilapidated.

Joao Silva/The New York Times

Jack Martins, 54, who lives in the neighborhood, had a cellphone repair shop in the complex, but it did not survive the riots. He now plies his trade from a table on the sidewalk. He secured public housing, but had to pay a bribe to get it, he said. Two of his sons could not get into university because there was not enough space, and his daughter, despite having a mechanical engineering degree, has been unable to find stable work. He is fed up with the near-daily, hourslong electricity outages caused by the failing state power utility.

“What is this government doing for us?” he said. “Absolutely nothing.”

The Black middle and upper classes have grown significantly. In 1995, just 350,000 Black South Africans lived in households that were among the top 15 percent in income, according to researchers at the University of Cape Town’s Liberty Institute of Strategic Marketing. By 2022, that number had grown to about 5.6 million.

Still, Black families are underrepresented among rich households.

Many expected something better this far into democracy. Much of the nation’s wealth remains in white hands.

Black South Africans had a stake in only 29 percent of the companies listed on the Johannesburg Stock Exchange, according to a 2022 report by South Africa’s Black Economic Empowerment Commission. Not a single entity on the exchange was fully Black-owned, the report said.

Economists say the country’s economy never took off enough to allow for a greater redistribution of wealth. Even when South Africa experienced its strongest stretch of economic growth in the first decade and a half of democracy, it still lagged behind its peers in Africa and other upper-middle-income countries. Since then, growth has been tepid, and contraction since the Covid-19 pandemic has been sharper than that in similarly sized economies.

8% annual GDP growth

Upper-middle-income

country average

Sub-Saharan

Africa average

South Africa

South Africa’s economic growth

has consistently lagged behind

Sources: Harvard Growth Lab analysis of World Economic Outlook (South Africa and sub-Saharan Africa) and World Development Indicators (upper-middle-income countries).

Government rules have allowed Black South Africans to gain a greater stake in industries like mining, where Black ownership has grown from 2 percent to 39 percent over the past two decades. But the gains have gone to relatively few people at the top.

However, the Bafokeng kingdom, an ethnic group within South Africa, has shown what is possible when a community gets its fair share of its resource wealth. The kingdom sits on rich platinum deposits. After a court victory in 1999 that affirmed its land rights, the kingdom used its platinum dividends to build a school with a large campus and a modern clinic, and to invest in other industries. Most families live in large brick homes that are the envy of other rural villages.

At the end of apartheid, when almost all of South Africa’s agricultural land was white-owned, Mr. Mandela’s government pledged in 1994 to transfer 30 percent of it into Black hands within a few years, by encouraging white landowners to sell.

The government failed to meet its goal, and it stretched the deadline to 2030. So far, about 25 percent of white-owned farmland has been transferred to Black ownership, mostly through the purchase of land by the government or Black individuals, according to Wandile Sihlobo and Johann Kirsten, agricultural economists at Stellenbosch University.

White South Africans make up roughly 7 percent of the population, but white-owned farms still cover about half of the country’s entire surface area, according to Mr. Sihlobo and Mr. Kirsten.

A worker on a Black-owned farm letting out cattle to graze near Carletonville, South Africa.

In the first decade of democracy, the government gave Black people full ownership of the white-owned farms it had bought. Owning the land meant that Black families had the chance not only to feed and support themselves but also advance.

But the government is no longer giving land to Black South Africans outright, offering long-term leases instead, Mr. Sihlobo and Mr. Kirsten said. Without ownership, Black farmers cannot generate wealth by using the land as collateral to get a bank loan. That has prevented Black farmers from expanding their operations to be commercially competitive.

Only about 7 percent of commercial-scale farms — those that sell to major grocers or export their products — are Black-owned. Only about 10 percent of the food produced by commercial farms in South Africa comes from Black-owned farms, about the same share as in the 1980s, Mr. Sihlobo said.

In the first decade of democracy, more than 930,000 mostly Black and colored farm workers were evicted from farms despite new laws intended to allow them to spend their lives on the farms where they worked.

“We haven’t been able to live up to those ideals” of Black land ownership, Mr. Sihlobo said.

Black South Africans are unemployed at far higher rates than their white peers, and that disparity has not improved over time.

50% unemployment rate

Black unemployment

The unemployment gap between

Black and white South Africans

remains wide.

White unemployment

Source: Statistics South Africa

Note: Graphic shows the expanded definition of unemployment, which includes those discouraged from seeking work.

The high unemployment rate has given rise to a hustle culture that sends many South Africans to the streets early each morning in search of work.

Zinhle Nene, 49, has been waking up by 5:30 a.m. most days and waiting on a corner in downtown Johannesburg with hundreds of others seeking day jobs. She left her low-paying job as a home health aide because the transportation to work was too expensive.

“It’s heartbreaking because we come here and we don’t even have food,” she said, wiping away tears as the hours passed. “Sometimes, you even get home, there’s nothing. You just drink water and then you sleep.”

Poverty has decreased since the start of democracy. Still, it remains very high. Nearly two out of every three Black South Africans lived below the upper-bound poverty line in 2015 — the most recent data available — meaning they had access to less than about $80 a month. Only 1 percent of white South Africans lived below that line.

Peter Mokoena broke down in tears last November inside the modest two-bedroom house the government had just given him. It sat alongside dozens of other homes just like it, on the freshly paved roads of a new subdivision about half an hour southeast of Johannesburg.

“I’m so happy, happy, happy, happy for this house,” said Mr. Mokoena, 74, who had been living in a tin shack so leaky that his furniture was soaked when it rained. “Now, it feels like I'm in heaven.”

The government has built 3.4 million houses since 1994, and given ownership of most of them for free to poor South Africans. Some units, known as social housing, are rented out at below-market rates. The government also has embarked on several “mega city” projects, in partnership with the private sector, to cluster together various types of housing and services like day care centers.

Many South Africans have moved into formal homes from makeshift structures, and access to basic services like electricity and piped water has increased. But frequent power and water outages have made those services unreliable, leading to anger and frustration nationwide.

Mr. Mokoena waited 27 years for his house. Many are still waiting. In the meantime, some squat in downtown buildings. Others build shacks in any open space they can find. Or they rent small backyard units built behind houses — an effort the government is supporting .

New government housing has often ended up in areas far from jobs and economic activity, perpetuating the apartheid system of marginalizing Black people to outlying townships.

JOHANNESBURG

Jobs in the city are concentrated in this area.

The area includes Sandton, a suburb that was

exclusively for white residents during

The densest populations are often far away.

Many of the densest places are townships,

like Soweto, where Black South Africans

were forced to live during apartheid

and where many new government

housing units have been built.

Population density

Jobs in the city are

concentrated in this

The area includes

Sandton, a suburb that

was exclusively for

white residents during

The densest populations are

often far away.

Many of the densest places are

in townships, like Soweto,

where Black South Africans

were forced to live during

apartheid and where many new

government housing units have

been built.

Sources: Spatial Tax Panel (employment data); WorldPop (population density)

Note: The area outlined in yellow represents parts of Johannesburg with at least 10,000 full-time equivalent employees in formal employment.

Nokuthula Mabe anxiously sat on her suitcase in the February heat outside North-West University in the city of Mahikeng, waiting with about a dozen other high-school graduates hoping for a spot. The university had received more than 181,000 applications for 11,717 slots.

In many ways, Ms. Mabe epitomized post-apartheid progress simply by graduating from her overcrowded village school near the Botswana border.

Nokuthula Mabe, right.

In the 1950s, only 10 percent of Black children finished high school. By 2021, that number had risen to 58 percent, according to government statistics.

Despite these gains, significant racial disparities persist.

100% completion rate

White high school

completion rate

Despite gains, there remains a

large education gap between

Black and white South Africans.

Black high school

Sources: Equal Education Law Centre analysis of data from Statistics South Africa General Household Survey; Department of Basic Education

Note: Shows share of 22- to 25-year-olds who have completed at least grade 12 or equivalent.

In 1982, the apartheid government spent roughly $1,100 a year on education for each white child but just $140 for each Black child, according to Section 27 , a human rights organization.

By 2018, that had increased to about $1,400 for each child, according to researchers at Stellenbosch University, much of it intended to level the playing field for Black students.

But schools are still failing many of their students. A report published in 2022 found that 81 percent of Grade 4 students could not understand what they were reading.

And while more children are finishing high school, there are not enough seats in colleges to meet the demand.

In 2022, about 6 percent of South Africans aged 18 to 29 were enrolled in higher education, according to Statistics South Africa. These enrollment rates lag behind countries with similarly sized economies, like Brazil, Mexico and the Philippines, according to figures from the World Bank .

After waiting nervously for hours, Ms. Mabe, 18, dragged her suitcase to the nearest bus stop to begin the three-and-a-half-hour trip back to her village. The university was too full to admit her.

During apartheid, the judicial system was used to criminalize Black people, mete out harsh punishment and cover up the atrocities committed against them.

Today, the judiciary is seen as among the most credible institutions in the country. Judges have upheld human rights and taken tough stances against even powerful political figures like the former president Jacob Zuma, who was sentenced to prison for contempt .

Still, as in many other countries, the South African justice system works best for those with money. A government commission found two years ago that most South Africans could not afford legal fees. The agency providing legal assistance for the poor is underfunded and overburdened.

“Those with very deep pockets are able to take the criminal justice process, stretch it for a very long period of time,” said Chrispin Phiri, a spokesman for the Ministry of Justice and Correctional Services. “That’s a privilege not afforded to a poorer person.”

What’s more, the justice system does not seem to be taming the country’s high crime rate.

70 murders per 100,000 residents

Murder rates are

on the rise.

70 per 100,000 residents

Sources: The Institute for Security Studies (South Africa); the World Bank (other countries, 2021 figures)

Although the murder rate is lower than it was in 1994, it has climbed steadily since 2012.

On paper, South Africa’s legal system prioritizes rehabilitating prisoners. The government offers an array of restorative justice, jobs and counseling programs for inmates and those being released.

In reality, though, prison-reform activists and studies suggest that treatment behind bars can be harsh and access to education difficult.

Internationally, South Africa has tried to position itself as a broker of peace and a leader in challenging a Western-led world order.

South Africa is the “S” in the BRICS group of nations that also includes Brazil, Russia, India and China, formed as a counterpoint to American and European alliances.

South Africa has played a critical role over the years in peace missions in African countries like Ethiopia, Burundi and Zimbabwe. And President Cyril Ramaphosa led a peace delegation last year to Ukraine and Russia, while refusing to condemn the Russian invasion of Ukraine.

President Cyril Ramaphosa in 2021.

South Africa argues that as a midsize nation, it cannot afford to choose sides and must make friends with everyone.

But it has been accused of being hypocritical and selectively concerned about peace and human rights.

The government brought a genocide case this year in the International Court of Justice against Israel for its war in Gaza after the attacks by Hamas on Oct. 7. South African officials have argued that Palestinians face a situation similar to apartheid.

For all of the frustrations that South Africans may have about the past 30 years, democracy has brought something that money and data cannot measure: freedom.

As in, freedom to go where you want, to date whom you want, to complain and advocate change as loudly as you want.

That has driven Sibusiso Zikode, 48, for much of his adult life.

He arrived in Durban, a port city on South Africa’s east coast, and started law school, but dropped out in the first term when his family savings ran out.

Sibusiso Zikode, left, helped establish a protest movement in Durban to advocate on behalf of poor people.

He moved to Kennedy Road, a slum built on muddy slopes and surrounded by a landfill, joining thousands who had flocked to the city for opportunity, only to find themselves in zinc shacks. This didn’t feel like freedom.

So, he helped to establish Abahlali baseMjondolo, a protest movement that is one of many that represent the revolt of poor people. Between July and September in 2022, the South African police responded to 2,455 protests.

But going up against the post-apartheid political establishment has come at great cost: Leaders of Abahlali have been assassinated, and Mr. Zikode had to flee from his home at the squatter camp after deadly attacks.

Abahlali’s members are growing more disillusioned with democracy.

“Whoever is homeless now,” Mr. Zikode said, “will be homeless after the election.”

- Share full article

Advertisement

America's Founding Documents

These three documents, known collectively as the Charters of Freedom, have secured the rights of the American people for more than two and a quarter centuries and are considered instrumental to the founding and philosophy of the United States.

Declaration of Independence

The Declaration of Independence expresses the ideals on which the United States was founded and the reasons for separation from Great Britain.

Read a Transcript

Constitution.

The Constitution defines the framework of the Federal Government of the United States.

Read a Transcript

Bill of rights.

The Bill of Rights is the first 10 amendments to the Constitution. It defines citizens’ and states’ rights in relation to the Government.

Read a Transcript

Shop the archives store.

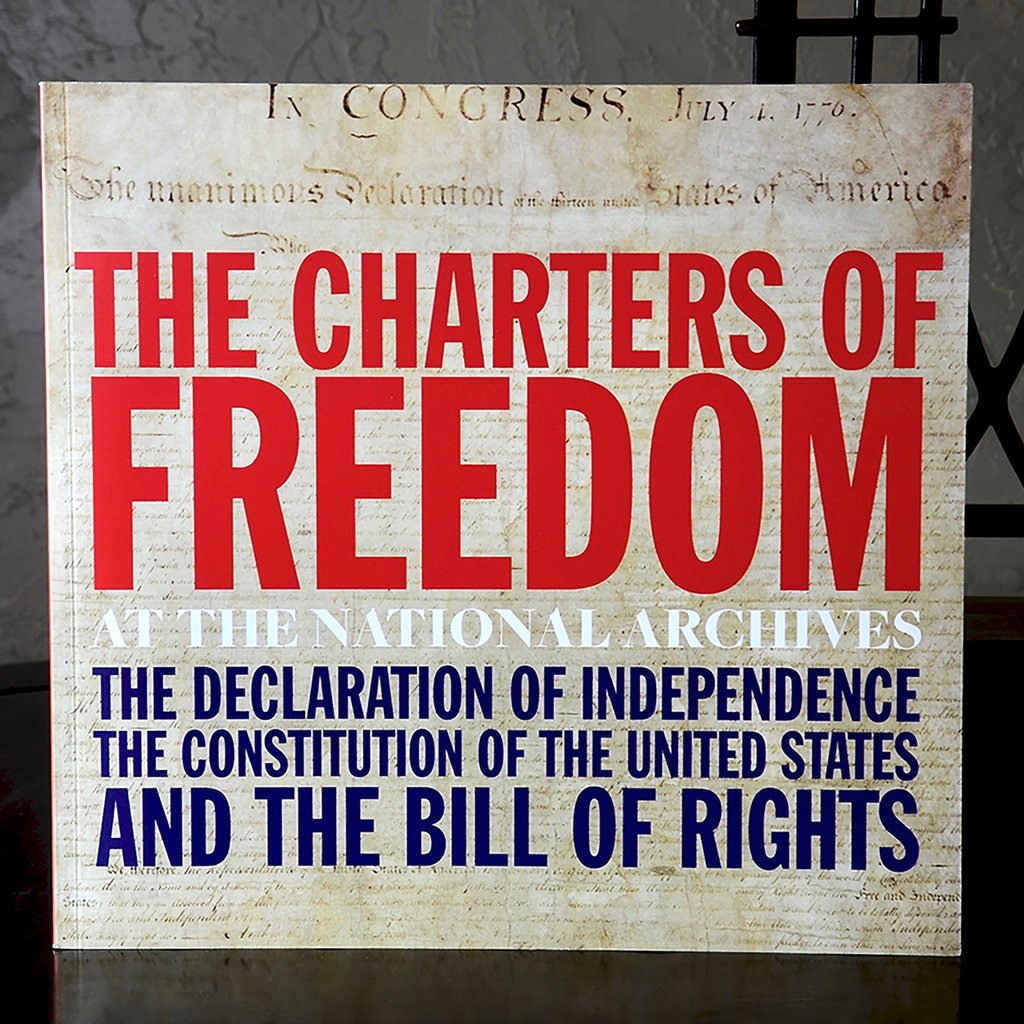

Charters of Freedom Book

This spectacular book written by Alice Kamps, Curator at the National Archives, showcases the National Archives' renovated Rotunda, the newly re-encased Charters of Freedom, and more.

Historic Facsimiles

Elegant facsimiles on parchment paper are perfect for educational purposes or to decorate your home or office.

Framed Documents

For the patriot and lover of our nation's history, get our founding documents framed and in your home.

Visit the Charters of Freedom

The rotunda for the charters of freedom.

Located on the upper level of the National Archives museum , the Rotunda for the Charters of Freedom is the permanent home of the original Declaration of Independence, Constitution of the United States, and Bill of Rights.

Designed by architect John Russell Pope as a shrine to American democracy, the ornate Rotunda with its soaring domed ceiling also features two murals by Barry Faulkner, depicting fictional scenes of the “presentations” of the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution.

Explore the Founders Online

Founders online.

Through Founders Online, you can read and search through thousands of documents and records to and from George Washington, Benjamin Franklin, Alexander Hamilton, John Adams, Thomas Jefferson, and James Madison and see firsthand the growth of democracy and the birth of the Republic. Their letters and journals are a kind of "first draft" of the Charters of Freedom.

View Other Milestone Documents

Milestone documents.

Milestone documents are primary source documents that highlight pivotal moments in the course of American history or government. They are some of the most-viewed and sought-out documents in the holdings of the National Archives.

BlackPast is dedicated to providing a global audience with reliable and accurate information on the history of African America and of people of African ancestry around the world. We aim to promote greater understanding through this knowledge to generate constructive change in our society.

(1955) the south african freedom charter.

The Freedom Charter

Adopted at the Congress of the People, Kliptown, on 26 June 1955 We, the People of South Africa, declare for all our country and the world to know:

that South Africa belongs to all who live in it, black and white, and that no government can justly claim authority unless it is based on the will of all the people;

that our people have been robbed of their birthright to land, liberty and peace by a form of government founded on injustice and inequality;

that our country will never be prosperous or free until all our people live in brotherhood, enjoying equal rights and opportunities;

that only a democratic state, based on the will of all the people, can secure to all their birthright without distinction of colour, race, sex or belief;

And therefore, we, the people of South Africa, black and white together equals, countrymen and brothers adopt this Freedom Charter;

And we pledge ourselves to strive together, sparing neither strength nor courage, until the democratic changes here set out have been won.

The People Shall Govern!

Every man and woman shall have the right to vote for and to stand as a candidate for all bodies which make laws;

All people shall be entitled to take part in the administration of the country;

The rights of the people shall be the same, regardless of race, colour or sex;

All bodies of minority rule, advisory boards, councils and authorities shall be replaced by democratic organs of self-government .

All National Groups Shall have Equal Rights!

There shall be equal status in the bodies of state, in the courts and in the schools for all national groups and races;

All people shall have equal right

All national groups shall be protected by law against insults to their race and national pride;

The preaching and practice of national, race or colour discrimination and contempt shall be a punishable crime;

All apartheid laws and practices shall be set aside.

The People Shall Share in the Country’s Wealth!

The national wealth of our country, the heritage of South Africans, shall be restored to the people;

The mineral wealth beneath the soil, the Banks and monopoly industry shall be transferred to the ownership of the people as a whole;

All other industry and trade shall be controlled to assist the wellbeing of the people;

All people shall have equal rights to trade where they choose, to manufacture and to enter all trades, crafts and professions.

The Land Shall be Shared Among Those Who Work It!

Restrictions of land ownership on a racial basis shall be ended, and all the land re-divided amongst those who work it to banish famine and land hunger;

The state shall help the peasants with implements, seed, tractors and dams to save the soil and assist the tillers;

Freedom of movement shall be guaranteed to all who work on the land;

All shall have the right to occupy land wherever they choose;

People shall not be robbed of their cattle, and forced labour and farm prisons shall be abolished.

All Shall be Equal Before the Law!

No-one shall be imprisoned, deported or restricted without a fair trial; No-one shall be condemned by the order of any Government official;

The courts shall be representative of all the people;

Imprisonment shall be only for serious crimes against the people, and shall aim at re-education, not vengeance;

The police force and army shall be open to all on an equal basis and shall be the helpers and protectors of the people;

All laws which discriminate on grounds of race, colour or belief shall be repealed.

All Shall Enjoy Equal Human Rights!

The law shall guarantee to all their right to speak, to organise, to meet together, to publish, to preach, to worship and to educate their children;

The privacy of the house from police raids shall be protected by law;

All shall be free to travel without restriction from countryside to town, from province to province, and from South Africa abroad;

Pass Laws, permits and all other laws restricting these freedoms shall be abolished.

There Shall be Work and Security!

All who work shall be free to form trade unions, to elect their officers and to make wage agreements with their employers;

The state shall recognise the right and duty of all to work, and to draw full unemployment benefits;

Men and women of all races shall receive equal pay for equal work;

There shall be a forty-hour working week, a national minimum wage, paid annual leave, and sick leave for all workers, and maternity leave on full pay for all working mothers;

Miners, domestic workers, farm workers and civil servants shall have the same rights as all others who work;

Child labour, compound labour, the tot system and contract labour shall be abolished.

The Doors of Learning and Culture Shall be Opened!

The government shall discover, develop and encourage national talent for the enhancement of our cultural life;

All the cultural treasures of mankind shall be open to all, by free exchange of books, ideas and contact with other lands;

The aim of education shall be to teach the youth to love their people and their culture, to honour human brotherhood, liberty and peace;

Education shall be free, compulsory, universal and equal for all children; Higher education and technical training shall be opened to all by means of state allowances and scholarships awarded on the basis of merit;

Adult illiteracy shall be ended by a mass state education plan;

Teachers shall have all the rights of other citizens;

The colour bar in cultural life, in sport and in education shall be abolished.

There Shall be Houses, Security and Comfort!

All people shall have the right to live where they choose, be decently housed, and to bring up their families in comfort and security;

Unused housing space to be made available to the people;

Rent and prices shall be lowered, food plentiful and no-one shall go hungry;

A preventive health scheme shall be run by the state;

Free medical care and hospitalisation shall be provided for all, with special care for mothers and young children;

Slums shall be demolished, and new suburbs built where all have transport, roads, lighting, playing fields, creches and social centres;

The aged, the orphans, the disabled and the sick shall be cared for by the state;

Rest, leisure and recreation shall be the right of all:

Fenced locations and ghettoes shall be abolished, and laws which break up families shall be repealed.

There Shall be Peace and Friendship!

South Africa shall be a fully independent state which respects the rights and sovereignty of all nations;

South Africa shall strive to maintain world peace and the settlement of all international disputes by negotiation – not war;

Peace and friendship amongst all our people shall be secured by upholding the equal rights, opportunities and status of all;

The people of the protectorates Basutoland, Bechuanaland and Swaziland shall be free to decide for themselves their own future;

The right of all peoples of Africa to independence and self-government shall be recognised, and shall be the basis of close co-operation.

Let all people who love their people and their country now say, as we say here:

THESE FREEDOMS WE WILL FIGHT FOR, SIDE BY SIDE, THROUGHOUT OUR LIVES, UNTIL WE HAVE WON OUR LIBERTY

Do you find this information helpful? A small donation would help us keep this available to all. Forego a bottle of soda and donate its cost to us for the information you just learned, and feel good about helping to make it available to everyone.

BlackPast.org is a 501(c)(3) non-profit and our EIN is 26-1625373. Your donation is fully tax-deductible.

Cite this entry in APA format:

Source of the author's information:.

African National Congress: South Africa’s National Liberation Movement, http://www.anc.org.za/show.php?doc=./ancdocs/history/charter.html; http://www.anc.org.za/

Your support is crucial to our mission.

Donate today to help us advance Black history education and foster a more inclusive understanding of our shared cultural heritage.

The Freedom Charter of 1955- South Africa

In June 1955, three thousand delegates of all ethnic origins met in Kliptown which is near Johannesburg. The delegates came from the ANC (African National Congress), the Indian Congress, Colored Peoples Congress, Congress of Trade Unions alliance. These organizations, together formed the Congress Alliance. The Congress Alliance came together to organize the Congress of the people a conference of all the people of South Africa which presented people`s demands for the kind of South Africa they wanted. The diverse group was comprised of doctors, peasants, ministers, domestic workers, students, city workers, teachers and housewives of all races and classes. They drafted, revised and adopted the Freedom Charter, which still forms the guiding principles for the ANC and other civic organizations. They called for:

- The people to govern and for the land to be shared by those who worked it

- Houses, work, and security and for

- Free and equal education.

As soon as this Charter was released the government claimed that the Freedom Charter was a communist document. This was an easy scapegoat because Communism was banned by the government in 1950, so they arrested ANC and Congress leaders and brought them to trial in the famous Treason Trial. They also tried to prove that the ANC and its allies had a policy of violence and planned to overthrown the state. The Freedom Charter declared that South Africa belongs to all who live in it.

A small minority of members, who called themselves Africanists, opposed the Freedom Charter. Not everyone in the ANC agreed with the policy of non racialism. They objected to the ANC`s growing co-operation with whites and Indians, who they described as foreigners. They were also suspicious of communists who, they felt, brought a foreign ideology into the struggle. The differences between the Africanists and those in the ANC who supported non-racialism, could not be overcome. In 1959, the Africanists broke away and formed the Pan Africanist Congress (PAC).

The Freedom Charter

As adopted at the Congress of the People, Kliptown, on 26 June 1955

We, the People of South Africa, declare for all our country and the world to know:

- that South Africa belongs to all who live in it, black and white, and that no government can justly claim authority unless it is based on the will of all the people;

- that our people have been robbed of their birthright to land, liberty and peace by a form of government founded on injustice and inequality;

- that our country will never be prosperous or free until all our people live in brotherhood, enjoying equal rights and opportunities;

- that only a democratic state, based on the will of all the people, can secure to all their birthright without distinction of colour, race, sex or belief;

And therefore, we, the people of South Africa, black and white together equals, countrymen and brothers adopt this Freedom Charter;

And we pledge ourselves to strive together, sparing neither strength nor courage, until the democratic changes here set out have been won.

The People Shall Govern!

- Every man and woman shall have the right to vote for and to stand as a candidate for all bodies which make laws;

- All people shall be entitled to take part in the administration of the country;

- The rights of the people shall be the same, regardless of race, colour or sex;

- All bodies of minority rule, advisory boards, councils and authorities shall be replaced by democratic organs of self-government .

All National Groups Shall have Equal Rights!

- There shall be equal status in the bodies of state, in the courts and in the schools for all national groups and races;

- All people shall have equal right to use their own languages, and to develop their own folk culture and customs;

- All national groups shall be protected by law against insults to their race and national pride;

- The preaching and practice of national, race or colour discrimination and contempt shall be a punishable crime;

- All apartheid laws and practices shall be set aside.

The People Shall Share in the Country`s Wealth!

- The national wealth of our country, the heritage of South Africans, shall be restored to the people;

- The mineral wealth beneath the soil, the Banks and monopoly industry shall be transferred to the ownership of the people as a whole;

- All other industry and trade shall be controlled to assist the well-being of the people;

- All people shall have equal rights to trade where they choose, to manufacture and to enter all trades, crafts and professions.

The Land Shall be Shared Among Those Who Work It!

- Restrictions of land ownership on a racial basis shall be ended, and all the land re-divided amongst those who work it to banish famine and land hunger;

- The state shall help the peasants with implements, seed, tractors and dams to save the soil and assist the tillers;

- Freedom of movement shall be guaranteed to all who work on the land;

- All shall have the right to occupy land wherever they choose;

- People shall not be robbed of their cattle, and forced labour and farm prisons shall be abolished.

All Shall be Equal Before the Law!

- No-one shall be imprisoned, deported or restricted without a fair trial; No-one shall be condemned by the order of any Government official;

- The courts shall be representative of all the people;

- Imprisonment shall be only for serious crimes against the people, and shall aim at re-education, not vengeance;

- The police force and army shall be open to all on an equal basis and shall be the helpers and protectors of the people;

- All laws which discriminate on grounds of race, colour or belief shall be repealed.

All Shall Enjoy Equal Human Rights!

- The law shall guarantee to all their right to speak, to organise, to meet together, to publish, to preach, to worship and to educate their children;

- The privacy of the house from police raids shall be protected by law;

- All shall be free to travel without restriction from countryside to town, from province to province, and from South Africa abroad;

- Pass Laws, permits and all other laws restricting these freedoms shall be abolished.

There Shall be Work and Security!

- All who work shall be free to form trade unions, to elect their officers and to make wage agreements with their employers;

- The state shall recognise the right and duty of all to work, and to draw full unemployment benefits;

- Men and women of all races shall receive equal pay for equal work;

- There shall be a forty-hour working week, a national minimum wage, paid annual leave, and sick leave for all workers, and maternity leave on full pay for all working mothers;

- Miners, domestic workers, farm workers and civil servants shall have the same rights as all others who work;

- Child labour, compound labour, the tot system and contract labour shall be abolished.

The Doors of Learning and Culture Shall be Opened!

- The government shall discover, develop and encourage national talent for the enhancement of our cultural life;

- All the cultural treasures of mankind shall be open to all, by free exchange of books, ideas and contact with other lands;

- The aim of education shall be to teach the youth to love their people and their culture, to honour human brotherhood, liberty and peace;

- Education shall be free, compulsory, universal and equal for all children; Higher education and technical training shall be opened to all by means of state allowances and scholarships awarded on the basis of merit;

- Adult illiteracy shall be ended by a mass state education plan;

- Teachers shall have all the rights of other citizens;

- The colour bar in cultural life, in sport and in education shall be abolished.

There Shall be Houses, Security and Comfort!

- All people shall have the right to live where they choose, be decently housed, and to bring up their families in comfort and security;

- Unused housing space to be made available to the people;

- Rent and prices shall be lowered, food plentiful and no-one shall go hungry;

- A preventive health scheme shall be run by the state;

- Free medical care and hospitalisation shall be provided for all, with special care for mothers and young children;

- Slums shall be demolished, and new suburbs built where all have transport, roads, lighting, playing fields, creches and social centres;

- The aged, the orphans, the disabled and the sick shall be cared for by the state;

- Rest, leisure and recreation shall be the right of all:

- Fenced locations and ghettoes shall be abolished, and laws which break up families shall be repealed.

- There Shall be Peace and Friendship!

- South Africa shall be a fully independent state which respects the rights and sovereignty of all nations;

- South Africa shall strive to maintain world peace and the settlement of all international disputes by negotiation – not war;

- Peace and friendship amongst all our people shall be secured by upholding the equal rights, opportunities and status of all;

- The people of the protectorates Basutoland, Bechuanaland and Swaziland shall be free to decide for themselves their own future;

- The right of all peoples of Africa to independence and self-government shall be recognised, and shall be the basis of close co-operation.

Let all people who love their people and their country now say, as we say here:

THESE FREEDOMS WE WILL FIGHT FOR, SIDE BY SIDE, THROUGHOUT OUR LIVES, UNTIL WE HAVE WON OUR LIBERTY

[purchase_link id=”3046″ text=”Add to Cart” style=”button” color=”green”]

Share this:

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on WhatsApp (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Reddit (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Pinterest (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Tumblr (Opens in new window)

- Click to print (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Telegram (Opens in new window)