How to Synthesize Written Information from Multiple Sources

Shona McCombes

Content Manager

B.A., English Literature, University of Glasgow

Shona McCombes is the content manager at Scribbr, Netherlands.

Learn about our Editorial Process

Saul Mcleod, PhD

Editor-in-Chief for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MRes, PhD, University of Manchester

Saul Mcleod, PhD., is a qualified psychology teacher with over 18 years of experience in further and higher education. He has been published in peer-reviewed journals, including the Journal of Clinical Psychology.

On This Page:

When you write a literature review or essay, you have to go beyond just summarizing the articles you’ve read – you need to synthesize the literature to show how it all fits together (and how your own research fits in).

Synthesizing simply means combining. Instead of summarizing the main points of each source in turn, you put together the ideas and findings of multiple sources in order to make an overall point.

At the most basic level, this involves looking for similarities and differences between your sources. Your synthesis should show the reader where the sources overlap and where they diverge.

Unsynthesized Example

Franz (2008) studied undergraduate online students. He looked at 17 females and 18 males and found that none of them liked APA. According to Franz, the evidence suggested that all students are reluctant to learn citations style. Perez (2010) also studies undergraduate students. She looked at 42 females and 50 males and found that males were significantly more inclined to use citation software ( p < .05). Findings suggest that females might graduate sooner. Goldstein (2012) looked at British undergraduates. Among a sample of 50, all females, all confident in their abilities to cite and were eager to write their dissertations.

Synthesized Example

Studies of undergraduate students reveal conflicting conclusions regarding relationships between advanced scholarly study and citation efficacy. Although Franz (2008) found that no participants enjoyed learning citation style, Goldstein (2012) determined in a larger study that all participants watched felt comfortable citing sources, suggesting that variables among participant and control group populations must be examined more closely. Although Perez (2010) expanded on Franz’s original study with a larger, more diverse sample…

Step 1: Organize your sources

After collecting the relevant literature, you’ve got a lot of information to work through, and no clear idea of how it all fits together.

Before you can start writing, you need to organize your notes in a way that allows you to see the relationships between sources.

One way to begin synthesizing the literature is to put your notes into a table. Depending on your topic and the type of literature you’re dealing with, there are a couple of different ways you can organize this.

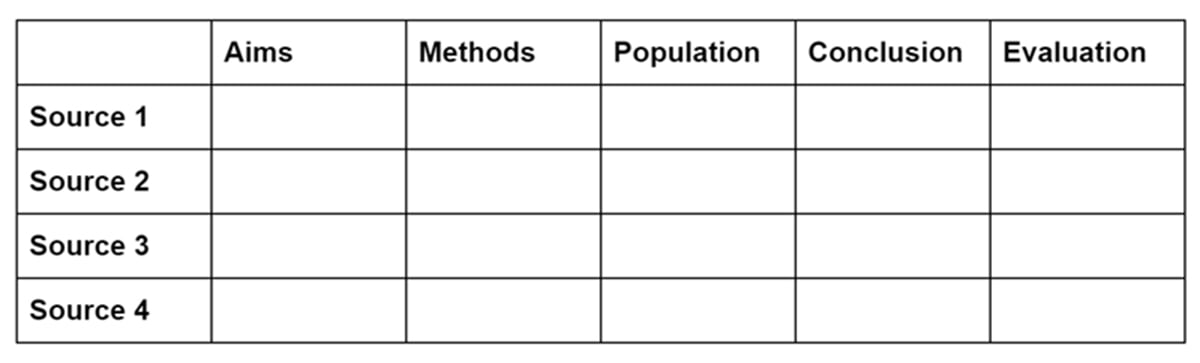

Summary table

A summary table collates the key points of each source under consistent headings. This is a good approach if your sources tend to have a similar structure – for instance, if they’re all empirical papers.

Each row in the table lists one source, and each column identifies a specific part of the source. You can decide which headings to include based on what’s most relevant to the literature you’re dealing with.

For example, you might include columns for things like aims, methods, variables, population, sample size, and conclusion.

For each study, you briefly summarize each of these aspects. You can also include columns for your own evaluation and analysis.

The summary table gives you a quick overview of the key points of each source. This allows you to group sources by relevant similarities, as well as noticing important differences or contradictions in their findings.

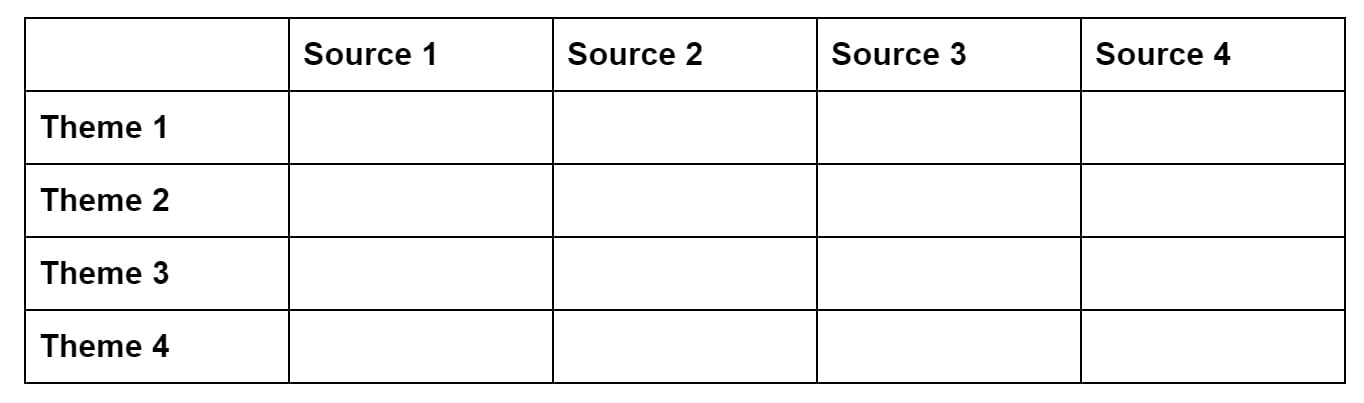

Synthesis matrix

A synthesis matrix is useful when your sources are more varied in their purpose and structure – for example, when you’re dealing with books and essays making various different arguments about a topic.

Each column in the table lists one source. Each row is labeled with a specific concept, topic or theme that recurs across all or most of the sources.

Then, for each source, you summarize the main points or arguments related to the theme.

The purposes of the table is to identify the common points that connect the sources, as well as identifying points where they diverge or disagree.

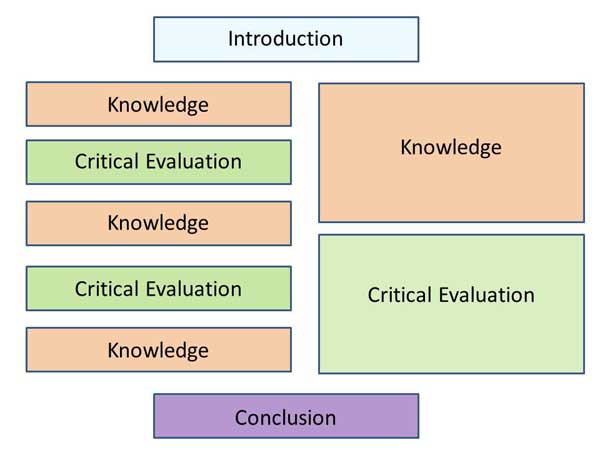

Step 2: Outline your structure

Now you should have a clear overview of the main connections and differences between the sources you’ve read. Next, you need to decide how you’ll group them together and the order in which you’ll discuss them.

For shorter papers, your outline can just identify the focus of each paragraph; for longer papers, you might want to divide it into sections with headings.

There are a few different approaches you can take to help you structure your synthesis.

If your sources cover a broad time period, and you found patterns in how researchers approached the topic over time, you can organize your discussion chronologically .

That doesn’t mean you just summarize each paper in chronological order; instead, you should group articles into time periods and identify what they have in common, as well as signalling important turning points or developments in the literature.

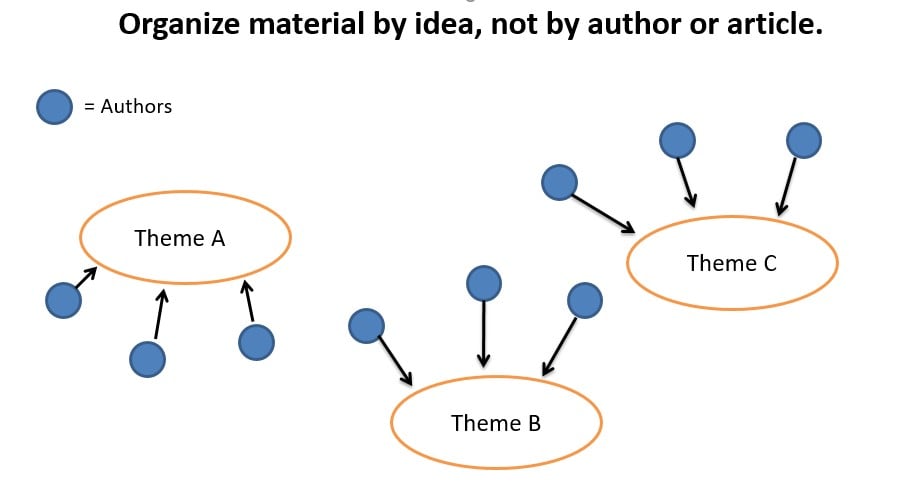

If the literature covers various different topics, you can organize it thematically .

That means that each paragraph or section focuses on a specific theme and explains how that theme is approached in the literature.

Source Used with Permission: The Chicago School

If you’re drawing on literature from various different fields or they use a wide variety of research methods, you can organize your sources methodologically .

That means grouping together studies based on the type of research they did and discussing the findings that emerged from each method.

If your topic involves a debate between different schools of thought, you can organize it theoretically .

That means comparing the different theories that have been developed and grouping together papers based on the position or perspective they take on the topic, as well as evaluating which arguments are most convincing.

Step 3: Write paragraphs with topic sentences

What sets a synthesis apart from a summary is that it combines various sources. The easiest way to think about this is that each paragraph should discuss a few different sources, and you should be able to condense the overall point of the paragraph into one sentence.

This is called a topic sentence , and it usually appears at the start of the paragraph. The topic sentence signals what the whole paragraph is about; every sentence in the paragraph should be clearly related to it.

A topic sentence can be a simple summary of the paragraph’s content:

“Early research on [x] focused heavily on [y].”

For an effective synthesis, you can use topic sentences to link back to the previous paragraph, highlighting a point of debate or critique:

“Several scholars have pointed out the flaws in this approach.” “While recent research has attempted to address the problem, many of these studies have methodological flaws that limit their validity.”

By using topic sentences, you can ensure that your paragraphs are coherent and clearly show the connections between the articles you are discussing.

As you write your paragraphs, avoid quoting directly from sources: use your own words to explain the commonalities and differences that you found in the literature.

Don’t try to cover every single point from every single source – the key to synthesizing is to extract the most important and relevant information and combine it to give your reader an overall picture of the state of knowledge on your topic.

Step 4: Revise, edit and proofread

Like any other piece of academic writing, synthesizing literature doesn’t happen all in one go – it involves redrafting, revising, editing and proofreading your work.

Checklist for Synthesis

- Do I introduce the paragraph with a clear, focused topic sentence?

- Do I discuss more than one source in the paragraph?

- Do I mention only the most relevant findings, rather than describing every part of the studies?

- Do I discuss the similarities or differences between the sources, rather than summarizing each source in turn?

- Do I put the findings or arguments of the sources in my own words?

- Is the paragraph organized around a single idea?

- Is the paragraph directly relevant to my research question or topic?

- Is there a logical transition from this paragraph to the next one?

Further Information

How to Synthesise: a Step-by-Step Approach

Help…I”ve Been Asked to Synthesize!

Learn how to Synthesise (combine information from sources)

How to write a Psychology Essay

Related Articles

Student Resources

How To Cite A YouTube Video In APA Style – With Examples

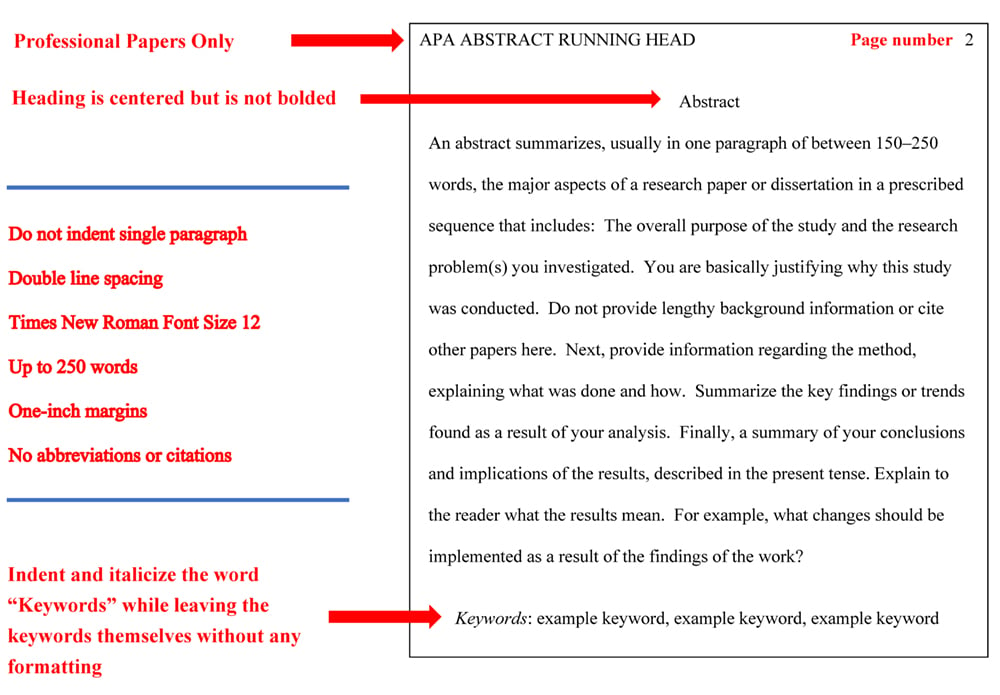

How to Write an Abstract APA Format

APA References Page Formatting and Example

APA Title Page (Cover Page) Format, Example, & Templates

How do I Cite a Source with Multiple Authors in APA Style?

How to Write a Psychology Essay

Purdue Online Writing Lab Purdue OWL® College of Liberal Arts

Synthesizing Sources

Welcome to the Purdue OWL

This page is brought to you by the OWL at Purdue University. When printing this page, you must include the entire legal notice.

Copyright ©1995-2018 by The Writing Lab & The OWL at Purdue and Purdue University. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, reproduced, broadcast, rewritten, or redistributed without permission. Use of this site constitutes acceptance of our terms and conditions of fair use.

When you look for areas where your sources agree or disagree and try to draw broader conclusions about your topic based on what your sources say, you are engaging in synthesis. Writing a research paper usually requires synthesizing the available sources in order to provide new insight or a different perspective into your particular topic (as opposed to simply restating what each individual source says about your research topic).

Note that synthesizing is not the same as summarizing.

- A summary restates the information in one or more sources without providing new insight or reaching new conclusions.

- A synthesis draws on multiple sources to reach a broader conclusion.

There are two types of syntheses: explanatory syntheses and argumentative syntheses . Explanatory syntheses seek to bring sources together to explain a perspective and the reasoning behind it. Argumentative syntheses seek to bring sources together to make an argument. Both types of synthesis involve looking for relationships between sources and drawing conclusions.

In order to successfully synthesize your sources, you might begin by grouping your sources by topic and looking for connections. For example, if you were researching the pros and cons of encouraging healthy eating in children, you would want to separate your sources to find which ones agree with each other and which ones disagree.

After you have a good idea of what your sources are saying, you want to construct your body paragraphs in a way that acknowledges different sources and highlights where you can draw new conclusions.

As you continue synthesizing, here are a few points to remember:

- Don’t force a relationship between sources if there isn’t one. Not all of your sources have to complement one another.

- Do your best to highlight the relationships between sources in very clear ways.

- Don’t ignore any outliers in your research. It’s important to take note of every perspective (even those that disagree with your broader conclusions).

Example Syntheses

Below are two examples of synthesis: one where synthesis is NOT utilized well, and one where it is.

Parents are always trying to find ways to encourage healthy eating in their children. Elena Pearl Ben-Joseph, a doctor and writer for KidsHealth , encourages parents to be role models for their children by not dieting or vocalizing concerns about their body image. The first popular diet began in 1863. William Banting named it the “Banting” diet after himself, and it consisted of eating fruits, vegetables, meat, and dry wine. Despite the fact that dieting has been around for over a hundred and fifty years, parents should not diet because it hinders children’s understanding of healthy eating.

In this sample paragraph, the paragraph begins with one idea then drastically shifts to another. Rather than comparing the sources, the author simply describes their content. This leads the paragraph to veer in an different direction at the end, and it prevents the paragraph from expressing any strong arguments or conclusions.

An example of a stronger synthesis can be found below.

Parents are always trying to find ways to encourage healthy eating in their children. Different scientists and educators have different strategies for promoting a well-rounded diet while still encouraging body positivity in children. David R. Just and Joseph Price suggest in their article “Using Incentives to Encourage Healthy Eating in Children” that children are more likely to eat fruits and vegetables if they are given a reward (855-856). Similarly, Elena Pearl Ben-Joseph, a doctor and writer for Kids Health , encourages parents to be role models for their children. She states that “parents who are always dieting or complaining about their bodies may foster these same negative feelings in their kids. Try to keep a positive approach about food” (Ben-Joseph). Martha J. Nepper and Weiwen Chai support Ben-Joseph’s suggestions in their article “Parents’ Barriers and Strategies to Promote Healthy Eating among School-age Children.” Nepper and Chai note, “Parents felt that patience, consistency, educating themselves on proper nutrition, and having more healthy foods available in the home were important strategies when developing healthy eating habits for their children.” By following some of these ideas, parents can help their children develop healthy eating habits while still maintaining body positivity.

In this example, the author puts different sources in conversation with one another. Rather than simply describing the content of the sources in order, the author uses transitions (like "similarly") and makes the relationship between the sources evident.

- University of Oregon Libraries

- Research Guides

How to Write a Literature Review

- 6. Synthesize

- Literature Reviews: A Recap

- Reading Journal Articles

- Does it Describe a Literature Review?

- 1. Identify the Question

- 2. Review Discipline Styles

- Searching Article Databases

- Finding Full-Text of an Article

- Citation Chaining

- When to Stop Searching

- 4. Manage Your References

- 5. Critically Analyze and Evaluate

Synthesis Visualization

Synthesis matrix example.

- 7. Write a Literature Review

- Synthesis Worksheet

About Synthesis

Approaches to synthesis.

You can sort the literature in various ways, for example:

How to Begin?

Read your sources carefully and find the main idea(s) of each source

Look for similarities in your sources – which sources are talking about the same main ideas? (for example, sources that discuss the historical background on your topic)

Use the worksheet (above) or synthesis matrix (below) to get organized

This work can be messy. Don't worry if you have to go through a few iterations of the worksheet or matrix as you work on your lit review!

Four Examples of Student Writing

In the four examples below, only ONE shows a good example of synthesis: the fourth column, or Student D . For a web accessible version, click the link below the image.

Long description of "Four Examples of Student Writing" for web accessibility

- Download a copy of the "Four Examples of Student Writing" chart

Click on the example to view the pdf.

From Jennifer Lim

- << Previous: 5. Critically Analyze and Evaluate

- Next: 7. Write a Literature Review >>

- Last Updated: May 3, 2024 5:17 PM

- URL: https://researchguides.uoregon.edu/litreview

Contact Us Library Accessibility UO Libraries Privacy Notices and Procedures

1501 Kincaid Street Eugene, OR 97403 P: 541-346-3053 F: 541-346-3485

- Visit us on Facebook

- Visit us on Twitter

- Visit us on Youtube

- Visit us on Instagram

- Report a Concern

- Nondiscrimination and Title IX

- Accessibility

- Privacy Policy

- Find People

Choose Your Test

Sat / act prep online guides and tips, how to write a perfect synthesis essay for the ap language exam.

Advanced Placement (AP)

If you're planning to take the AP Language (or AP Lang) exam , you might already know that 55% of your overall exam score will be based on three essays. The first of the three essays you'll have to write on the AP Language exam is called the "synthesis essay." If you want to earn full points on this portion of the AP Lang Exam, you need to know what a synthesis essay is and what skills are assessed by the AP Lang synthesis essay.

In this article, we'll explain the different aspects of the AP Lang synthesis essay, including what skills you need to demonstrate in your synthesis essay response in order to achieve a good score. We'll also give you a full breakdown of a real AP Lang Synthesis Essay prompt, provide an analysis of an AP Lang synthesis essay example, and give you four tips for how to write a synthesis essay.

Let's get started by taking a closer look at how the AP Lang synthesis essay works!

Synthesis Essay AP Lang: What It Is and How It Works

The AP Lang synthesis essay is the first of three essays included in the Free Response section of the AP Lang exam.

The AP Lang synthesis essay portion of the Free Response section lasts for one hour total . This hour consists of a recommended 15 minute reading period and a 40 minute writing period. Keep in mind that these time allotments are merely recommendations, and that exam takers can parse out the allotted 60 minutes to complete the synthesis essay however they choose.

Now, here's what the structure of the AP Lang synthesis essay looks like. The exam presents six to seven sources that are organized around a specific topic (like alternative energy or eminent domain, which are both past synthesis exam topics).

Of these six to seven sources, at least two are visual , including at least one quantitative source (like a graph or pie chart, for example). The remaining four to five sources are print text-based, and each one contains approximately 500 words.

In addition to six to seven sources, the AP Lang exam provides a written prompt that consists of three paragraphs. The prompt will briefly explain the essay topic, then present a claim that students will respond to in an essay that synthesizes material from at least three of the sources provided.

Here's an example prompt provided by the College Board:

Directions : The following prompt is based on the accompanying six sources.

This question requires you to integrate a variety of sources into a coherent, well-written essay. Refer to the sources to support your position; avoid mere paraphrase or summary. Your argument should be central; the sources should support this argument .

Remember to attribute both direct and indirect citations.

Introduction

Television has been influential in United States presidential elections since the 1960's. But just what is this influence, and how has it affected who is elected? Has it made elections fairer and more accessible, or has it moved candidates from pursuing issues to pursuing image?

Read the following sources (including any introductory information) carefully. Then, in an essay that synthesizes at least three of the sources for support, take a position that defends, challenges, or qualifies the claim that television has had a positive impact on presidential elections.

Refer to the sources as Source A, Source B, etc.; titles are included for your convenience.

Source A (Campbell) Source B (Hart and Triece) Source C (Menand) Source D (Chart) Source E (Ranney) Source F (Koppel)

Like we mentioned earlier, this prompt gives you a topic — which it briefly explains — then asks you to take a position. In this case, you'll have to choose a stance on whether television has positively or negatively affected U.S. elections. You're also given six sources to evaluate and use in your response. Now that you have everything you need, now your job is to write an amazing synthesis essay.

But what does "synthesize" mean, exactly? According to the CollegeBoard, when an essay prompt asks you to synthesize, it means that you should "combine different perspectives from sources to form a support of a coherent position" in writing. In other words, a synthesis essay asks you to state your claim on a topic, then highlight the relationships between several sources that support your claim on that topic. Additionally, you'll need to cite specific evidence from your sources to prove your point.

The synthesis essay counts for six of the total points on the AP Lang exam . Students can receive 0-1 points for writing a thesis statement in the essay, 0-4 based on incorporation of evidence and commentary, and 0-1 points based on sophistication of thought and demonstrated complex understanding of the topic.

You'll be evaluated based on how effectively you do the following in your AP Lang synthesis essay:

Write a thesis that responds to the exam prompt with a defensible position

Provide specific evidence that to support all claims in your line of reasoning from at least three of the sources provided, and clearly and consistently explain how the evidence you include supports your line of reasoning

Demonstrate sophistication of thought by either crafting a thoughtful argument, situating the argument in a broader context, explaining the limitations of an argument

Make rhetorical choices that strengthen your argument and/or employ a vivid and persuasive style throughout your essay.

If your synthesis essay meets the criteria above, then there's a good chance you'll score well on this portion of the AP Lang exam!

If you're looking for even more information on scoring, the College Board has posted the AP Lang Free Response grading rubric on its website. ( You can find it here. ) We recommend taking a close look at it since it includes additional details about the synthesis essay scoring.

Don't be intimidated...we're going to teach you how to break down even the hardest AP synthesis essay prompt.

Full Breakdown of a Real AP Lang Synthesis Essay Prompt

In this section, we'll teach you how to analyze and respond to a synthesis essay prompt in five easy steps, including suggested time frames for each step of the process.

Step 1: Analyze the Prompt

The very first thing to do when the clock starts running is read and analyze the prompt. To demonstrate how to do this, we'll look at the sample AP Lang synthesis essay prompt below. This prompt comes straight from the 2018 AP Lang exam:

Eminent domain is the power governments have to acquire property from private owners for public use. The rationale behind eminent domain is that governments have greater legal authority over lands within their dominion than do private owners. Eminent domain has been instituted in one way or another throughout the world for hundreds of years.

Carefully read the following six sources, including the introductory information for each source. Then synthesize material from at least three of the sources and incorporate it into a coherent, well-developed essay that defends, challenges, or qualifies the notion that eminent domain is productive and beneficial.

Your argument should be the focus of your essay. Use the sources to develop your argument and explain the reasoning for it. Avoid merely summarizing the sources. Indicate clearly which sources you are drawing from, whether through direct quotation, paraphrase, or summary. You may cite the sources as Source A, Source B, etc., or by using the descriptions in parentheses.

On first read, you might be nervous about how to answer this prompt...especially if you don't know what eminent domain is! But if you break the prompt down into chunks, you'll be able to figure out what the prompt is asking you to do in no time flat.

To get a full understanding of what this prompt wants you to do, you need to identify the most important details in this prompt, paragraph by paragraph. Here's what each paragraph is asking you to do:

- Paragraph 1: The prompt presents and briefly explains the topic that you'll be writing your synthesis essay about. That topic is the concept of eminent domain.

- Paragraph 2: The prompt presents a specific claim about the concept of eminent domain in this paragraph: Eminent domain is productive and beneficial. This paragraph instructs you to decide whether you want to defend, challenge, or qualify that claim in your synthesis essay , and use material from at least three of the sources provided in order to do so.

- Paragraph 3: In the last paragraph of the prompt, the exam gives you clear instructions about how to approach writing your synthesis essay . First, make your argument the focus of the essay. Second, use material from at least three of the sources to develop and explain your argument. Third, provide commentary on the material you include, and provide proper citations when you incorporate quotations, paraphrases, or summaries from the sources provided.

So basically, you'll have to agree with, disagree with, or qualify the claim stated in the prompt, then use at least three sources substantiate your answer. Since you probably don't know much about eminent domain, you'll probably decide on your position after you read the provided sources.

To make good use of your time on the exam, you should spend around 2 minutes reading the prompt and making note of what it's asking you to do. That will leave you plenty of time to read the sources provided, which is the next step to writing a synthesis essay.

Step 2: Read the Sources Carefully

After you closely read the prompt and make note of the most important details, you need to read all of the sources provided. It's tempting to skip one or two sources to save time--but we recommend you don't do this. That's because you'll need a thorough understanding of the topic before you can accurately address the prompt!

For the sample exam prompt included above, there are six sources provided. We're not going to include all of the sources in this article, but you can view the six sources from this question on the 2018 AP Lang exam here . The sources include five print-text sources and one visual source, which is a cartoon.

As you read the sources, it's important to read quickly and carefully. Don't rush! Keep your pencil in hand to quickly mark important passages that you might want to use as evidence in your synthesis. While you're reading the sources and marking passages, you want to think about how the information you're reading influences your stance on the issue (in this case, eminent domain).

When you finish reading, take a few seconds to summarize, in a phrase or sentence, whether the source defends, challenges, or qualifies whether eminent domain is beneficial (which is the claim in the prompt) . Though it might not feel like you have time for this, it's important to give yourself these notes about each source so you know how you can use each one as evidence in your essay.

Here's what we mean: say you want to challenge the idea that eminent domain is useful. If you've jotted down notes about each source and what it's saying, it will be easier for you to pull the relevant information into your outline and your essay.

So how much time should you spend reading the provided sources? The AP Lang exam recommends taking 15 minutes to read the sources . If you spend around two of those minutes reading and breaking down the essay prompt, it makes sense to spend the remaining 13 minutes reading and annotating the sources.

If you finish reading and annotating early, you can always move on to drafting your synthesis essay. But make sure you're taking your time and reading carefully! It's better to use a little extra time reading and understanding the sources now so that you don't have to go back and re-read the sources later.

A strong thesis will do a lot of heavy lifting in your essay. (See what we did there?)

Step 3: Write a Strong Thesis Statement

After you've analyzed the prompt and thoroughly read the sources, the next thing you need to do in order to write a good synthesis essay is write a strong thesis statement .

The great news about writing a thesis statement for this synthesis essay is that you have all the tools you need to do it at your fingertips. All you have to do in order to write your thesis statement is decide what your stance is in relationship to the topic provided.

In the example prompt provided earlier, you're essentially given three choices for how to frame your thesis statement: you can either defend, challenge, or qualify a claim that's been provided by the prompt, that eminent domain is productive and beneficial . Here's what that means for each option:

If you choose to defend the claim, your job will be to prove that the claim is correct . In this case, you'll have to show that eminent domain is a good thing.

If you choose to challenge the claim, you'll argue that the claim is incorrect. In other words, you'll argue that eminent domain isn't productive or beneficial.

If you choose to qualify, that means you'll agree with part of the claim, but disagree with another part of the claim. For instance, you may argue that eminent domain can be a productive tool for governments, but it's not beneficial for property owners. Or maybe you argue that eminent domain is useful in certain circumstances, but not in others.

When you decide whether you want your synthesis essay to defend, challenge, or qualify that claim, you need to convey that stance clearly in your thesis statement. You want to avoid simply restating the claim provided in the prompt, summarizing the issue without making a coherent claim, or writing a thesis that doesn't respond to the prompt.

Here's an example of a thesis statement that received full points on the eminent domain synthesis essay:

Although eminent domain can be misused to benefit private interests at the expense of citizens, it is a vital tool of any government that intends to have any influence on the land it governs beyond that of written law.

This thesis statement received full points because it states a defensible position and establishes a line of reasoning on the issue of eminent domain. It states the author's position (that some parts of eminent domain are good, but others are bad), then goes on to explain why the author thinks that (it's good because it allows the government to do its job, but it's bad because the government can misuse its power.)

Because this example thesis statement states a defensible position and establishes a line of reasoning, it can be elaborated upon in the body of the essay through sub-claims, supporting evidence, and commentary. And a solid argument is key to getting a six on your synthesis essay for AP Lang!

Step 4: Create a Bare-Bones Essay Outline

Once you've got your thesis statement drafted, you have the foundation you need to develop a bare bones outline for your synthesis essay. Developing an outline might seem like it's a waste of your precious time, but if you develop your outline well, it will actually save you time when you start writing your essay.

With that in mind, we recommend spending 5 to 10 minutes outlining your synthesis essay . If you use a bare-bones outline like the one below, labeling each piece of content that you need to include in your essay draft, you should be able to develop out the most important pieces of the synthesis before you even draft the actual essay.

To help you see how this can work on test day, we've created a sample outline for you. You can even memorize this outline to help you out on test day! In the outline below, you'll find places to fill in a thesis statement, body paragraph topic sentences, evidence from the sources provided, and commentary :

- Present the context surrounding the essay topic in a couple of sentences (this is a good place to use what you learned about the major opinions or controversies about the topic from reading your sources).

- Write a straightforward, clear, and concise thesis statement that presents your stance on the topic

- Topic sentence presenting first supporting point or claim

- Evidence #1

- Commentary on Evidence #1

- Evidence #2 (if needed)

- Commentary on Evidence #2 (if needed)

- Topic sentence presenting second supporting point or claim

- Topic sentence presenting three supporting point or claim

- Sums up the main line of reasoning that you developed and defended throughout the essay

- Reiterates the thesis statement

Taking the time to develop these crucial pieces of the synthesis in a bare-bones outline will give you a map for your final essay. Once you have a map, writing the essay will be much easier.

Step 5: Draft Your Essay Response

The great thing about taking a few minutes to develop an outline is that you can develop it out into your essay draft. After you take about 5 to 10 minutes to outline your synthesis essay, you can use the remaining 30 to 35 minutes to draft your essay and review it.

Since you'll outline your essay before you start drafting, writing the essay should be pretty straightforward. You'll already know how many paragraphs you're going to write, what the topic of each paragraph will be, and what quotations, paraphrases, or summaries you're going to include in each paragraph from the sources provided. You'll just have to fill in one of the most important parts of your synthesis—your commentary.

Commentaries are your explanation of why your evidence supports the argument you've outlined in your thesis. Your commentary is where you actually make your argument, which is why it's such a critical part of your synthesis essay.

When thinking about what to say in your commentary, remember one thing the AP Lang synthesis essay prompt specifies: don't just summarize the sources. Instead, as you provide commentary on the evidence you incorporate, you need to explain how that evidence supports or undermines your thesis statement . You should include commentary that offers a thoughtful or novel perspective on the evidence from your sources to develop your argument.

One very important thing to remember as you draft out your essay is to cite your sources. The AP Lang exam synthesis essay prompt indicates that you can use generic labels for the sources provided (e.g. "Source 1," "Source 2," "Source 3," etc.). The exam prompt will indicate which label corresponds with which source, so you'll need to make sure you pay attention and cite sources accurately. You can cite your sources in the sentence where you introduce a quote, summary, or paraphrase, or you can use a parenthetical citation. Citing your sources affects your score on the synthesis essay, so remembering to do this is important.

Keep reading for a real-life example of a great AP synthesis essay response!

Real-Life AP Synthesis Essay Example and Analysis

If you're still wondering how to write a synthesis essay, examples of real essays from past AP Lang exams can make things clearer. These real-life student AP synthesis essay responses can be great for helping you understand how to write a synthesis essay that will knock the graders' socks off .

While there are multiple essay examples online, we've chosen one to take a closer look at. We're going to give you a brief analysis of one of these example student synthesis essays from the 2019 AP Lang Exam below!

Example Synthesis Essay AP Lang Response

To get started, let's look at the official prompt for the 2019 synthesis essay:

In response to our society's increasing demand for energy, large-scale wind power has drawn attention from governments and consumers as a potential alternative to traditional materials that fuel our power grids, such as coal, oil, natural gas, water, or even newer sources such as nuclear or solar power. Yet the establishment of large-scale, commercial-grade wind farms is often the subject of controversy for a variety of reasons.

Carefully read the six sources, found on the AP English Language and Composition 2019 Exam (Question 1), including the introductory information for each source. Write an essay that synthesizes material from at least three of the sources and develops your position on the most important factors that an individual or agency should consider when deciding whether to establish a wind farm.

Source A (photo) Source B (Layton) Source C (Seltenrich) Source D (Brown) Source E (Rule) Source F (Molla)

In your response you should do the following:

- Respond to the prompt with a thesis presents a defensible position.

- Select and use evidence from at least 3 of the provided sources to support your line of reasoning. Indicate clearly the sources used through direct quotation, paraphrase, or summary. Sources may be cited as Source A, Source B, etc., or by using the description in parentheses.

- Explain how the evidence supports your line of reasoning.

- Use appropriate grammar and punctuation in communicating your argument.

Now that you know exactly what the prompt asked students to do on the 2019 AP Lang synthesis essay, here's an AP Lang synthesis essay example, written by a real student on the AP Lang exam in 2019:

[1] The situation has been known for years, and still very little is being done: alternative power is the only way to reliably power the changing world. The draw of power coming from industry and private life is overwhelming current sources of non-renewable power, and with dwindling supplies of fossil fuels, it is merely a matter of time before coal and gas fuel plants are no longer in operation. So one viable alternative is wind power. But as with all things, there are pros and cons. The main factors for power companies to consider when building wind farms are environmental boon, aesthetic, and economic factors.

[2] The environmental benefits of using wind power are well-known and proven. Wind power is, as qualified by Source B, undeniably clean and renewable. From their production requiring very little in the way of dangerous materials to their lack of fuel, besides that which occurs naturally, wind power is by far one of the least environmentally impactful sources of power available. In addition, wind power by way of gearbox and advanced blade materials, has the highest percentage of energy retention. According to Source F, wind power retains 1,164% of the energy put into the system – meaning that it increases the energy converted from fuel (wind) to electricity 10 times! No other method of electricity production is even half that efficient. The efficiency and clean nature of wind power are important to consider, especially because they contribute back to power companies economically.

[3] Economically, wind power is both a boon and a bone to electric companies and other users. For consumers, wind power is very cheap, leading to lower bills than from any other source. Consumers also get an indirect reimbursement by way of taxes (Source D). In one Texan town, McCamey, tax revenue increased 30% from a wind farm being erected in the town. This helps to finance improvements to the town. But, there is no doubt that wind power is also hurting the power companies. Although, as renewable power goes, wind is incredibly cheap, it is still significantly more expensive than fossil fuels. So, while it is helping to cut down on emissions, it costs electric companies more than traditional fossil fuel plants. While the general economic trend is positive, there are some setbacks which must be overcome before wind power can take over as truly more effective than fossil fuels.

[4] Aesthetics may be the greatest setback for power companies. Although there may be significant economic and environmental benefit to wind power, people will always fight to preserve pure, unspoiled land. Unfortunately, not much can be done to improve the visual aesthetics of the turbines. White paint is the most common choice because it "[is] associated with cleanliness." (Source E). But, this can make it stand out like a sore thumb, and make the gargantuan machines seem more out of place. The site can also not be altered because it affects generating capacity. Sound is almost worse of a concern because it interrupts personal productivity by interrupting people's sleep patterns. One thing for power companies to consider is working with turbine manufacturing to make the machines less aesthetically impactful, so as to garner greater public support.

[5] As with most things, wind power has no easy answer. It is the responsibility of the companies building them to weigh the benefits and the consequences. But, by balancing economics, efficiency, and aesthetics, power companies can create a solution which balances human impact with environmental preservation.

And that's an entire AP Lang synthesis essay example, written in response to a real AP Lang exam prompt! It's important to remember AP Lang exam synthesis essay prompts are always similarly structured and worded, and students often respond in around the same number of paragraphs as what you see in the example essay response above.

Next, let's analyze this example essay and talk about what it does effectively, where it could be improved upon, and what score past exam scorers awarded it.

To get started on an analysis of the sample synthesis essay, let's look at the scoring commentary provided by the College Board:

- For development of thesis, the essay received 1 out of 1 possible points

- For evidence and commentary, the essay received 4 out of 4 possible points

- For sophistication of thought, the essay received 0 out of 1 possible points.

This means that the final score for this example essay was a 5 out of 6 possible points . Let's look more closely at the content of the example essay to figure out why it received this score breakdown.

Thesis Development

The thesis statement is one of the three main categories that is taken into consideration when you're awarded points on this portion of the exam. This sample essay received 1 out of 1 total points.

Now, here's why: the thesis statement clearly and concisely conveys a position on the topic presented in the prompt--alternative energy and wind power--and defines the most important factors that power companies should consider when deciding whether to establish a wind farm.

Evidence and Commentary

The second key category taken into consideration when synthesis exams are evaluated is incorporation of evidence and commentary. This sample received 4 out of 4 possible points for this portion of the synthesis essay. At bare minimum, this sample essay meets the requirement mentioned in the prompt that the writer incorporate evidence from at least three of the sources provided.

On top of that, the writer does a good job of connecting the incorporated evidence back to the claim made in the thesis statement through effective commentary. The commentary in this sample essay is effective because it goes beyond just summarizing what the provided sources say. Instead, it explains and analyzes the evidence presented in the selected sources and connects them back to supporting points the writer makes in each body paragraph.

Finally, the writer of the essay also received points for evidence and commentary because the writer developed and supported a consistent line of reasoning throughout the essay . This line of reasoning is summed up in the fourth paragraph in the following sentence: "One thing for power companies to consider is working with turbine manufacturing to make the machines less aesthetically impactful, so as to garner greater public support."

Because the writer did a good job consistently developing their argument and incorporating evidence, they received full marks in this category. So far, so good!

Sophistication of Thought

Now, we know that this essay received a score of 5 out of 6 total points, and the place where the writer lost a point was on the basis of sophistication of thought, for which the writer received 0 out of 1 points. That's because this sample essay makes several generalizations and vague claims where it could have instead made specific claims that support a more balanced argument.

For example, in the following sentence from the 5th paragraph of the sample essay, the writer misses the opportunity to state specific possibilities that power companies should consider for wind energy . Instead, the writer is ambiguous and non-committal, saying, "As with most things, wind power has no easy answer. It is the responsibility of the companies building them to weigh the benefits and consequences."

If the writer of this essay was interested in trying to get that 6th point on the synthesis essay response, they could consider making more specific claims. For instance, they could state the specific benefits and consequences power companies should consider when deciding whether to establish a wind farm. These could include things like environmental impacts, economic impacts, or even population density!

Despite losing one point in the last category, this example synthesis essay is a strong one. It's well-developed, thoughtfully written, and advances an argument on the exam topic using evidence and support throughout.

4 Tips for How to Write a Synthesis Essay

AP Lang is a timed exam, so you have to pick and choose what you want to focus on in the limited time you're given to write the synthesis essay. Keep reading to get our expert advice on what you should focus on during your exam.

Tip 1: Read the Prompt First

It may sound obvious, but when you're pressed for time, it's easy to get flustered. Just remember: when it comes time to write the synthesis essay, read the prompt first !

Why is it so important to read the prompt before you read the sources? Because when you're aware of what kind of question you're trying to answer, you'll be able to read the sources more strategically. The prompt will help give you a sense of what claims, points, facts, or opinions to be looking for as you read the sources.

Reading the sources without having read the prompt first is kind of like trying to drive while wearing a blindfold: you can probably do it, but it's likely not going to end well!

Tip 2: Make Notes While You Read

During the 15-minute reading period at the beginning of the synthesis essay, you'll be reading through the sources as quickly as you can. After all, you're probably anxious to start writing!

While it's definitely important to make good use of your time, it's also important to read closely enough that you understand your sources. Careful reading will allow you to identify parts of the sources that will help you support your thesis statement in your essay, too.

As you read the sources, consider marking helpful passages with a star or check mark in the margins of the exam so you know which parts of the text to quickly re-read as you form your synthesis essay. You might also consider summing up the key points or position of each source in a sentence or a few words when you finish reading each source during the reading period. Doing so will help you know where each source stands on the topic given and help you pick the three (or more!) that will bolster your synthesis argument.

Tip 3: Start With the Thesis Statement

If you don't start your synthesis essay with a strong thesis statement, it's going to be tough to write an effective synthesis essay. As soon as you finish reading and annotating the provided sources, the thing you want to do next is write a strong thesis statement.

According to the CollegeBoard grading guidelines for the AP Lang synthesis essay, a strong thesis statement will respond to the prompt— not restate or rephrase the prompt. A good thesis will take a clear, defensible position on the topic presented in the prompt and the sources.

In other words, to write a solid thesis statement to guide the rest of your synthesis essay, you need to think about your position on the topic at hand and then make a claim about the topic based on your position. This position will either be defending, challenging, or qualifying the claim made in the essay's prompt.

The defensible position that you establish in your thesis statement will guide your argument in the rest of the essay, so it's important to do this first. Once you have a strong thesis statement, you can begin outlining your essay.

Tip 4: Focus on Your Commentary

Writing thoughtful, original commentary that explains your argument and your sources is important. In fact, doing this well will earn you four points (out of a total of six)!

AP Lang provides six to seven sources for you on the exam, and you'll be expected to incorporate quotations, paraphrases, or summaries from at least three of those sources into your synthesis essay and interpret that evidence for the reader.

While incorporating evidence is very important, in order to get the extra point for "sophistication of thought" on the synthesis essay, it's important to spend more time thinking about your commentary on the evidence you choose to incorporate. The commentary is your chance to show original thinking, strong rhetorical skills, and clearly explain how the evidence you've included supports the stance you laid out in your thesis statement.

To earn the 6th possible point on the synthesis essay, make sure your commentary demonstrates a nuanced understanding of the source material, explains this nuanced understanding, and places the evidence incorporated from the sources in conversation with each other. To do this, make sure you're avoiding vague language. Be specific when you can, and always tie your commentary back to your thesis!

What's Next?

There's a lot more to the AP Language exam than just the synthesis essay. Be sure to check out our expert guide to the entire exam , then learn more about the tricky multiple choice section .

Is the AP Lang exam hard...or is it easy? See how it stacks up to other AP tests on our list of the hardest AP exams .

Did you know there are technically two English AP exams? You can learn more about the second English AP test, the AP Literature exam, in this article . And if you're confused about whether you should take the AP Lang or AP Lit test , we can help you make that decision, too.

Ashley Sufflé Robinson has a Ph.D. in 19th Century English Literature. As a content writer for PrepScholar, Ashley is passionate about giving college-bound students the in-depth information they need to get into the school of their dreams.

Ask a Question Below

Have any questions about this article or other topics? Ask below and we'll reply!

Improve With Our Famous Guides

- For All Students

The 5 Strategies You Must Be Using to Improve 160+ SAT Points

How to Get a Perfect 1600, by a Perfect Scorer

Series: How to Get 800 on Each SAT Section:

Score 800 on SAT Math

Score 800 on SAT Reading

Score 800 on SAT Writing

Series: How to Get to 600 on Each SAT Section:

Score 600 on SAT Math

Score 600 on SAT Reading

Score 600 on SAT Writing

Free Complete Official SAT Practice Tests

What SAT Target Score Should You Be Aiming For?

15 Strategies to Improve Your SAT Essay

The 5 Strategies You Must Be Using to Improve 4+ ACT Points

How to Get a Perfect 36 ACT, by a Perfect Scorer

Series: How to Get 36 on Each ACT Section:

36 on ACT English

36 on ACT Math

36 on ACT Reading

36 on ACT Science

Series: How to Get to 24 on Each ACT Section:

24 on ACT English

24 on ACT Math

24 on ACT Reading

24 on ACT Science

What ACT target score should you be aiming for?

ACT Vocabulary You Must Know

ACT Writing: 15 Tips to Raise Your Essay Score

How to Get Into Harvard and the Ivy League

How to Get a Perfect 4.0 GPA

How to Write an Amazing College Essay

What Exactly Are Colleges Looking For?

Is the ACT easier than the SAT? A Comprehensive Guide

Should you retake your SAT or ACT?

When should you take the SAT or ACT?

Stay Informed

Get the latest articles and test prep tips!

Looking for Graduate School Test Prep?

Check out our top-rated graduate blogs here:

GRE Online Prep Blog

GMAT Online Prep Blog

TOEFL Online Prep Blog

Holly R. "I am absolutely overjoyed and cannot thank you enough for helping me!”

Chapter 5: Writing a Summary and Synthesizing

5.5 Synthesis and Literature Reviews

Literature reviews : synthesis and research.

Why do we seek to understand the ways that authors or sources “converse” with one another? So that we can synthesize various perspectives on a topic to more deeply understand it.

In academic writing, this understanding of the “conversation” may become the content of an explanatory synthesis paper – a paper in which you, the writer, point out various various themes or key points from a conversation on a particular topic. Notice that the example of synthesis in “What Synthesis Is” acknowledges that guns and gun control inspire passionate responses in Americans, that more than one kind of weapon is involved in gun violence, that guns in America are both legally and illegally owned, and that there are many constituencies whose experience with guns needs to considered if sound gun-control policy is to be achieved. The writer of this synthesis isn’t “pretending” to be objective (“Although gun violence is a problem in American today, people who want to increase gun control clearly don’t understand the Second Amendment”); nor is the writer arguing a point or attempting to persuade the audience to accept one perspective. The writer is making a claim about gun control that demonstrates his or her deepest understanding of the issue.

Another assignment that you may complete that also applies your synthesis skills is a l iterature review . Literature reviews are often found in the beginning of scholarly journal articles to contextualize the author’s own research. Sometimes, literature reviews are done for their own sake; some scholarly articles are just Literature reviews.

Literature reviews (sometimes shortened to “lit reviews”) synthesize previous research that has been done on a particular topic, summarizing important works in the history of research on that topic. The literature review provides context for the author’s own new research. It is the basis and background out of which the author’s research grows. Context = credibility in academic writing. When writers are able to produce a literature review, they demonstrate the breadth of their knowledge about how others have already studied and discussed their topic.

- Literature reviews are most often arranged by topic or theme , much like a traditional explanatory synthesis paper.

- If one is looking at a topic that has a long history of research and scholarship, one may conduct a chronological literature review, one that looks at how the research topic has been studied and discussed in various time periods (i.e., what was published ten years ago, five years ago, and within the last year, for example).

- Finally, in some instances, one might seek to craft a literature review that is organized by discipline or field. This type of literature review could offer information about how different academic fields have examined a particular topic (i.e., what is the current research being done by biologists on this topic? What is the current research being done by psychologists on this topic? What is the current research being done by [ insert academic discipline] on this topic?).

A Literature Review offers only a report on what others have already written about. The Literature Review does not reflect the author’s own argument or contributions to the field of research. Instead, it indicates that the author has read others’ important contributions and understands what has come before him or her. Sometimes, literature reviews are stand alone assignments or publications. Sometimes, they fit into a larger essay or article (especially in many of the scholarly articles that you will read throughout college. For more information on how literature reviews are a part of scholarly articles, see chapter 10.5 )

A Guide to Rhetoric, Genre, and Success in First-Year Writing by Melanie Gagich & Emilie Zickel is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Feedback/Errata

Comments are closed.

APPENDIX C: Peer Review Forms

Peer reviews are very helpful. You can get feedback from classmates about your writing. In addition, you can read another classmate’s work and learn more about how other students write. Finally, by comparing and contrasting your work with a classmate’s, you can have a very useful discussion about what how to improve your research and writing skills. However, it’s not always easy to know where to start or what to focus on. And often it is not helpful to try to do it all. So here are some guided peer review forms for each essay that help you to focus on the things you are learning in this class. Your peer will be able to use your concrete feedback, and you will have a better idea of what to look for in your own writing, too!

Guided peer review form for Essay 01

Guided peer review form for Essay 03

Synthesis Copyright © 2022 by Timothy Krause is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Digital transformation: a review, synthesis and opportunities for future research

- Open access

- Published: 18 April 2020

- Volume 71 , pages 233–341, ( 2021 )

Cite this article

You have full access to this open access article

- Swen Nadkarni 1 &

- Reinhard Prügl 1

150k Accesses

288 Citations

11 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

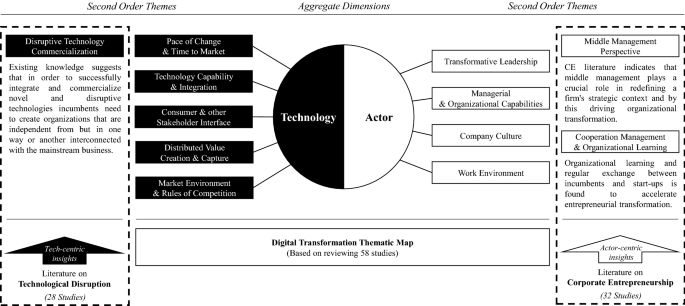

In the last years, scholarly attention was on a steady rise leading to a significant increase in the number of papers addressing different technological and organizational aspects of digital transformation. In this paper, we consolidate existing findings which mainly stem from the literature of information systems, map the territory by sharing important macro- and micro-level observations, and propose future research opportunities for this pervasive field. The paper systematically reviews 58 peer-reviewed studies published between 2001 and 2019, dealing with different aspects of digital transformation. Emerging from our review, we develop inductive thematic maps which identify technology and actor as the two aggregate dimensions of digital transformation. For each dimension, we derive further units of analysis (nine core themes in total) which help to disentangle the particularities of digital transformation processes and thereby emphasize the most influential and unique antecedents and consequences. In a second step, in order to assist in breaking down disciplinary silos and strengthen the management perspective, we supplement the resulting state-of-the-art of digital transformation by integrating cross-disciplinary contributions from reviewing 28 papers on technological disruption and 32 papers on corporate entrepreneurship. The review reveals that certain aspects, such as the pace of transformation, the culture and work environment, or the middle management perspective are significantly underdeveloped.

Similar content being viewed by others

Digital Transformation: A Literature Review and Guidelines for Future Research

An Introduction to Digital Transformation

Digital Transformation Framework: A Bibliometric Approach

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Digital transformation, defined as transformation ‘concerned with the changes digital technologies can bring about in a company’s business model, … products or organizational structures’ (Hess et al. 2016 , p. 124), is perhaps the most pervasive managerial challenge for incumbent firms of the last and coming decades. However, digital possibilities need to come together with skilled employees and executives in order to reveal its transformative power. Thus, digital transformation needs both technology and people. In the last years, scholarly attention, particularly in the information systems (IS) literature, was on a steady rise leading to a significant increase in the number of papers addressing different technological and organizational aspects of digital transformation. In the light of this development, we are convinced it is the right time to map the territory and reflect on the current state of knowledge. Therefore, in this paper we aim at providing a descriptive, thematic analysis of the field by critically assessing where, how and by whom research on digital transformation is conducted. Based on this analysis, we identify future research opportunities.

We approach this objective in two steps. First, we adopt an inductive approach and conduct a systematic literature review (following Tranfield et al. 2003 ; Webster and Watson 2002 ) of 58 peer-reviewed papers dealing with digital transformation. By applying elements of grounded theory and content analysis (Corley and Gioia 2004 ; Gioia et al. 1994 ) we identify important core themes in the literature that are particularly pronounced and/or unique in transformations enabled by digital technologies. In a second step, in order to assist in breaking down disciplinary silos (Jones and Gatrell 2014 ) and avoiding the building of an ivory tower (Bartunek et al. 2006 ; Fuetsch and Suess-Reyes 2017 ), we supplement the pre-dominantly IS-based digital transformation literature with a broader management perspective. Accordingly, we integrate cross-disciplinary contributions from reviewing 28 papers on technological disruption and 32 papers on corporate entrepreneurship.

We find these research fields particularly suitable for informing digital transformation research for two reasons. First, by reviewing the literature on technological disruption we hope to derive implications regarding technology adoption and integration. Burdened with the legacy of old technology, bureaucratic structures and core rigidities (Leonard-Barton 1992 ), incumbents may face major challenges in this respect during their digital transformation journey. Second, we expect corporate entrepreneurship to add a more holistic perspective on firm-internal aspects during the process of transformation, such as management influence or the impact of knowledge and organizational learning.

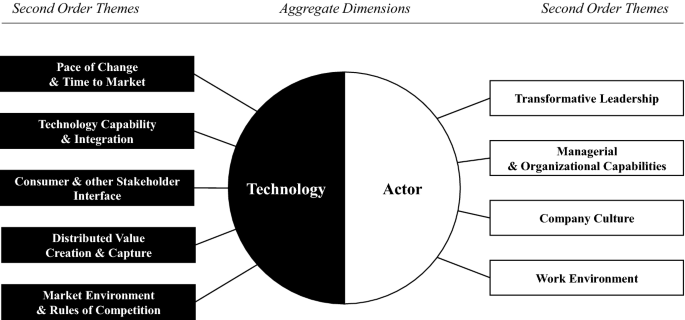

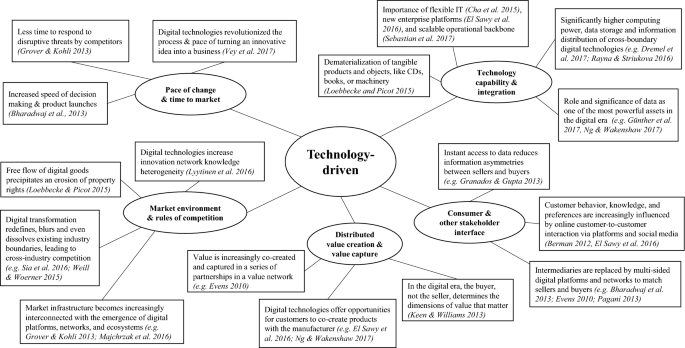

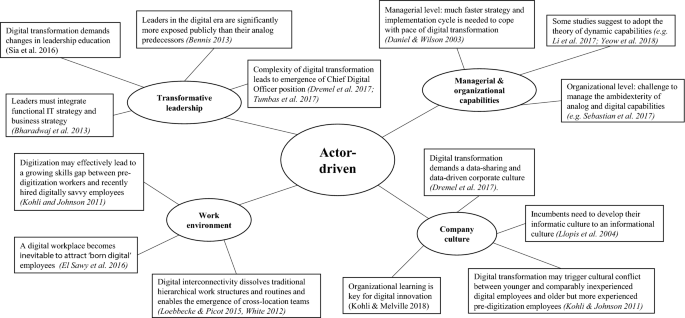

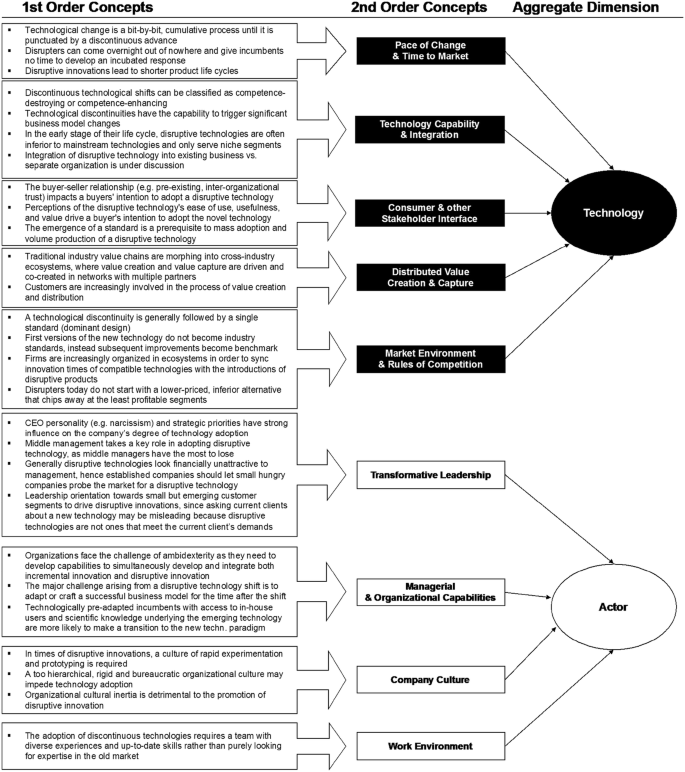

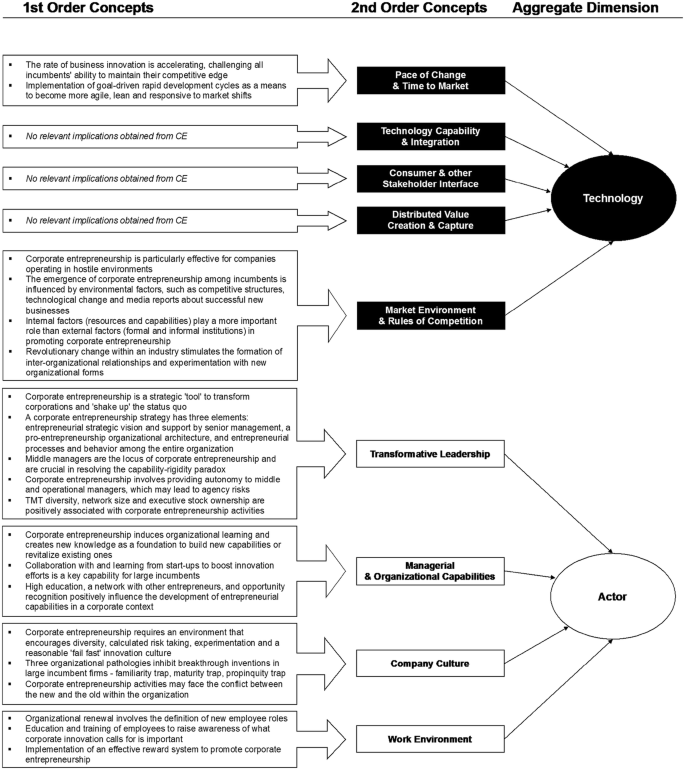

Our findings and related contributions are threefold: First, based on a systematic and structured analysis we develop digital transformation maps which inductively categorize and describe the existing body of research. These thematic maps identify technology and actor as the two aggregate dimensions of digital transformation. Within these dimensions, we reveal nine core themes which help to disentangle the particularities of digital transformation processes and thereby emphasize the most influential and unique antecedents and consequences of this specific type of transformation. Thus, it becomes possible to identify the predominant contextual factors for which research would create the strongest leverage for a better understanding of the challenges inherent in digital transformation. Second, we contribute to the advancement of this field by elaborating opportunities for future research on digital transformation which integrate the three perspectives mentioned above. In particular, informed by corporate entrepreneurship, we find that the important middle management perspective on digital transformation has thus far been largely neglected by researchers. Also, emerging from our review we call for more studies on the various options for integrating digital transformation within organizational architectures and existing processes. Third, in reviewing the adjacent literature on technological disruption and corporate entrepreneurship, we strengthen the valuable management perspective within the primarily IS-based discussion on digital transformation. This way we avoid the reinvention of the wheel while at the same time enable the identification of cross-disciplinary research opportunities. We hope to stimulate discussion between these different but strongly related disciplines and enable mutual learning and a fruitful exchange of ideas.

2 Conceptual foundations

Technology as a major determinant of organizational form and structure has been well acknowledged by academics for a long time (Thompson and Bates 1957 ; Woodward 1965 ; Scott 1992 ). Following a significant decline of interest in this relationship until the mid-1990s (Zammuto et al. 2007 ), innovations in information technologies (IT) and the rise of pre-internet technologies have revitalized its relevance in the context of organizational transformation. Thus, the literature on IT-enabled organizational transformation, a concept which originates from the field of information systems (IS) that has caught considerable academic attention starting back in the early 1990s (Ranganathan et al. 2004 ; Besson and Rowe 2012 ), may be seen as one of the scholarly roots of digital transformation research. In his seminal book, Morton ( 1991 ) argued that companies must experience fundamental transformations for effective IT implementation. In the course of the years a shift of attention occurred from technological to managerial and organizational issues (Markus and Benjamin 1997 ; Doherty and King 2005 ). Non-technological aspects such as leadership, culture, and employee training were found to be equally important for successful IT-enabled transformation (Markus 2004 ). This is supported by Orlikowski ( 1996 ) who found empirical evidence from a 2-year case study that organizational transformation was in fact enabled by technology, but not caused by it.

Today, information technologies have become ‘one of the threads from which the fabric of organization is now woven’ (Zammuto et al. 2007 , p. 750). Digital technologies are considered a major asset for leveraging organizational transformation, given their disruptive nature and cross-organizational and systemic effects (Besson and Rowe 2012 ). In order to achieve successful digital transformation, changes must occur at various levels within the organization, including an adaptation of the core business (Karimi and Walter 2015 ), the exchange of resources and capabilities (Cha et al. 2015 ; Yeow et al. 2018 ), the reconfiguration of processes and structures (Resca et al. 2013 ), adjustments in leadership (Hansen and Sia 2015 ; Singh and Hess 2017 ), and the implementation of a vivid digital culture (Llopis et al. 2004 ). Therefore, the scope of our review revolves around digital transformation at the organizational level only (in contrast to implications at the individual level).

In this study, we conceptualize digital transformation at the intercept of the adoption of disruptive digital technologies on the one side and actor-guided organizational transformation of capabilities, structures, processes and business model components on the other side. In other words, and in line with Hess et al. ( 2016 ), we define digital transformation as organizational change triggered by digital technologies. Hence, we argue that two perspectives of digital transformation within organizations must be captured: a technology-centric and an actor-centric perspective. To exploit the technology-centric perspective we include the literature on technological disruption (e.g. Tushman and Anderson 1986 ; Anderson and Tushman 1990 ) and merge it with research on digital transformation. For the actor-centric perspective, we derive essential implications from the field of corporate entrepreneurship (Guth and Ginsberg 1990 ), which we believe may add valuable insights regarding actor-driven innovation and renewal processes within firms. In the following, we offer a brief introduction to both concepts and their relationship with digital transformation.

Rice et al. ( 1998 ) define disruptive innovations as ‘game changers’ which have the potential ‘(1) for a 5–10 times improvement in performance compared to existing products; (2) to create the basis for a 30–50% reduction in costs; or (3) to have new-to-the world performance features’ (p. 52). Similarly, Utterback ( 1994 ) emphasizes this disruptiveness at the firm and industry level and provides a similar ‘game changer’ definition in terms of ‘change that sweeps away much of a firm’s existing investment in technical skills and knowledge, designs, production technique, plant and equipment’ (p. 200). Tushman and Anderson ( 1986 ) distinguish between product and process disruptiveness. Product disruptiveness encompasses new product classes, product substitutions, or fundamental product improvements. Process disruptiveness may take the form of process substitutions or process innovations which radically improve industry-specific dimensions of merit. Christensen and Raynor ( 2003 ) introduce a further form of disruptive innovations, namely disruptive business model innovations, which represent the implementation of fundamentally different business models in an existing business.

We argue that digital technologies may reflect in all of these definitions of disruptive innovation. They may represent new-to-the-world product innovations, dislocate existing processes, and open up entirely new business models. As resumed in a recent study by Li et al. ( 2017 ), e-commerce for instance is defined as a disruptive technology (Johnson 2010 ) which involves significant changes to an organization’s culture, business processes, capabilities, and markets (Zeng et al. 2008 ; Cui and Pan 2015 ).

Corporate entrepreneurship (CE) on the other side is a multi-dimensional concept at the intersection of entrepreneurship and strategic management in existing organizations (Zahra 1996 ; Hitt et al. 2001 ; Dess et al. 2003 ). We adopt the conceptualization proposed by Guth and Ginsberg ( 1990 , p. 5), who argue that corporate entrepreneurship deals with two phenomena ‘(1) the birth of new businesses within existing organizations, i.e. internal innovation or venturing, and (2) the transformation of organizations through renewal of the key ideas on which they are built, i.e. strategic renewal.’ Particularly the aspect of strategic renewal in corporate entrepreneurship, also labelled as strategic change, revival, transformation (Schendel 1990 ), reorganization, redefinition (Zahra 1993 ), or organizational renewal (Stopford and Baden-Fuller 1994 ), provides a promising interface to digital transformation. As stated by Covin and Miles ( 1999 , p. 50), corporate entrepreneurship ‘revitalizes, reinvigorates and reinvents’—processes also required for digital transformation. Various authors have stated that corporate entrepreneurship is a vehicle to improve competitive positioning and transform corporations (Schollhammer 1982 ; Miller 1983 ; Khandwalla 1987 ; Guth and Ginsberg 1990 ; Naman and Slevin 1993 ; Lumpkin and Dess 1996 ). Considering the disruptive nature of many current digital technologies, we believe that organizations need to fundamentally renew and redefine the key ideas of their business in order to fully exploit the potential of digitization and eventually achieve successful transformation. The literature places particular attention on the role of middle managers as the locus of corporate entrepreneurship (Burgelman 1983 , Floyd and Wooldridge 1999 ). Concluding, we will review the research on corporate entrepreneurship and identify those contributions which we believe may offer valuable knowledge regarding actor-driven internal renewal and change processes in the light of digital transformation.

Our review of the literature on digital transformation, technological disruption and corporate entrepreneurship is conducted in a two-step approach. First, we review, analyze and synthesize existing articles on digital transformation. Then, in a second step we supplement these findings be simultaneously reviewing the literature stream on technological disruption and corporate entrepreneurship. We believe a separate analysis and contrasting of the research streams is appropriate for two reasons: first, it provides the reader with more clarity on the status quo of digital transformation knowledge and prevents the confusion of concepts emerging from different literature fields. Second, white spots and opportunities for future research regarding digital transformation become much more visible in such a structured approach.

3 Research methodology

A systematic review is a type of literature review that applies an explicit algorithm and a multi-stage review strategy in order to collect and critically appraise a body of research studies (Mulrow 1994 ; Pittaway et al. 2004 ; Crossan and Apaydin 2010 ). This transparent and reproducible process is ideally suited for analyzing and structuring the vast and heterogeneous literature on digital transformation. In conducting our review, we followed the guidelines of Tranfield et al. ( 2003 ) and the recommendations of Denyer and Neely ( 2004 , p. 133) Footnote 1 as well as Fisch and Block ( 2018 ) in order to ensure a high quality of the review.

The nature of our review is both scoping and descriptive (Rowe 2014 ; Paré et al. 2015 ) as we aim to provide an initial indication of the potential size and nature of the available literature as well as to summarize and map existing findings from digital transformation research. By developing opportunities for future research, our review further contributes to the advancement of this field and stimulates theory development.

For the purpose of data collection, we exclusively limit our focus on peer-reviewed academic journals as recommended by McWilliams et al. ( 2005 ). Thus, we opted to exclude work in progress, conference papers, dissertations, or books. First, based on discussion among the authors and the reading of a few highly-cited papers, we designed our search criteria using combinations of keywords containing ‘ digital* AND transform*’ , ‘ digital* AND disrupt*’ , ‘ digitalization’ , and ‘ digitization ’. Then, we manually searched each issue of each volume of the leading journals in the management Footnote 2 and IS field (AIS Basket of eight). Footnote 3 In addition, we run our search query against five different electronic databases: Business Source Premier (EBSCO) , Scopus , Science Direct , Social Sciences Citation Index (SSCI) , and Google Scholar . We used all years available and only included articles referring to business, management, or economics in order to exclude irrelevant publications. We abstained from including digital innovation in our search (the only exception in our sample is a recent literature review by Kohli and Melville ( 2019 ), in order to capture consolidated insights). Although we realize that it is a hot topic in IS research at the moment (e.g. Fichman et al. 2014 ; Nambisan et al. 2017 ; Yoo et al. 2010 , 2012 ), we aim to concentrate our focus on papers dealing with digital transformation on a broader level (firm and industry), rather than with transitions within innovation management.