If you're seeing this message, it means we're having trouble loading external resources on our website.

If you're behind a web filter, please make sure that the domains *.kastatic.org and *.kasandbox.org are unblocked.

To log in and use all the features of Khan Academy, please enable JavaScript in your browser.

World history

Course: world history > unit 3, causes and effects of human migration.

- Key concepts: Human Migration

- Focus on causation: Human migration

- Migration is the movement of people from one place to another with the intent to settle

- Causes: In preindustrial societies, environmental factors, such as the need for resources due to overpopulation, were often the cause of migration

- Effects: As people migrated, they brought new plants, animals, and technologies that had effects on the environment

Causes of migration

- (Choice A) Temporary movement that follows seasonal weather patterns A Temporary movement that follows seasonal weather patterns

- (Choice B) Movement to a new region with the intent to settle there B Movement to a new region with the intent to settle there

- (Choice C) Continuous movement to follow resources C Continuous movement to follow resources

Causes of migration in Africa

Causes of migration in the pacific.

- (Choice A) Iron farming tools and weapons A Iron farming tools and weapons

- (Choice B) Long-term food preservation techniques B Long-term food preservation techniques

- (Choice C) Types of canoes that could sail in the open ocean C Types of canoes that could sail in the open ocean

Effects of migration

- (Choice A) Rats eating eggs and greatly reducing the bird population A Rats eating eggs and greatly reducing the bird population

- (Choice B) Intense storms that altered the landscape of the island B Intense storms that altered the landscape of the island

- (Choice C) Human activity, such as hunting and cutting down trees C Human activity, such as hunting and cutting down trees

- Jerry Bentley, et al, Traditions and Encounters , Vol. 1 (New York: McGraw Hill, 2015), 284.

- Douglas L. Oliver, Polynesia in Prehistoric Times (Honolulu: Bess Press, 2002), 32-35.

- Oliver, 232, 239.

Want to join the conversation?

- Upvote Button navigates to signup page

- Downvote Button navigates to signup page

- Flag Button navigates to signup page

Search form

The Past, Present, and Future of Human Migration

Thursday, June 29, 2017

By Abigail Meisel Illustrations by Chris Gash

Displacement. Poverty. Persecution. Economic opportunity. These are some of the many reasons that people migrate to countries thousands of miles from their ancestral homelands. In modern history, major demographic transitions have included the influx of immigrants to the U.S. from the mid-1800s to the early 20th century; the flow of humanity at the end of World War II, when tens of millions of people, particularly in Europe, were sundered from their native countries by years of violent conflict; and the movement of more than 17 million Africans within their continent in the 21st century. Today, more than 200 million people—most from Latin America, South Asia, and Africa—are migrants both within and across continents.

“Migration is now a big part of the global economy and of global society,” says Hans-Peter Kohler, Frederick J. Warren Professor of Demography and a Research Associate in the Population Studies Center.

Although migration is a complex story, many Americans and Europeans see it in simplistic terms, according to Tukufu Zuberi, Lasry Family Professor of Race Relations and Professor of Sociology and Africana Studies: There are “natives,” who belong, and “foreigners,” who do not. New cultures, languages, and economic demands of immigrants have roiled Western societies in the past decade, making migration a new locus of international concern.

To better understand the mass movement of populations across the globe, Penn social science faculty are interpreting data, analyzing the effect of immigration on sending and receiving countries, and untangling the many complexities of immigration today. Their work offers new perspectives on how mass migration shapes our world.

Unwelcoming Neighbors

When Zuberi studied the response of largely white Washington, D.C. neighborhoods to an influx of migrants, the results surprised him.

“When there is more diversity, whites are less tolerant of those of other races,” Zuberi said. “We used to think exactly the opposite. It made sense that the more diverse a city was, the less segregated it would be. That turns out not to be true.”

Zuberi, a demographer whose primary interest is in the African diaspora, published his findings in Sociology of Race and Ethnicity in 2015.

Putting the rise of segregation in D.C. into global context, Zuberi looks at larger social changes afoot in the U.S. and in Western Europe.

On a worldwide level, he explains, dramatic immigration shifts are going to create radical changes in the identity of populations. The influx of nonwhite groups into the U.S. and Europe—particularly the U.S., France, the U.K., and Germany—has whites there “singing an anti-immigrant note.”

“Whites have regarded themselves as a nation’s ‘first-class’ citizens, but immigration is increasingly challenging this view as nonwhite communities continue to grow,” Zuberi says.

Demographic studies show that the U.S. will become a “minority majority” population in the 21st century, meaning that nonwhites will comprise the majority of the U.S. population.

According to Zuberi, this is just the latest chapter in a long, and often violent, history of demographic shifts on the North American continent.

“White Europeans displaced the indigenous peoples here and also brought in a large group of enslaved individuals. And now whites are being displaced,” he said.

He sees the recent presidential election as “the reaction of white people to their own demographic demise,” and added, “Race is the problem in America and in the Western world now.”

Melding into Society

Michael Jones-Correa, Professor of Political Science, examines the opinions, behavior and policy preferences of Latino immigrants to the U.S. He served as co-principal investigator of the 2006 Latino National Survey, a national state-stratified survey of Latinos in the U.S.

Jones-Correa sees our era as the “end of consensus, both in the U.S. and Europe, that immigration is necessarily a good thing.” Immigration, he feels, was a central value to Western society, and it was a given that letting immigrants in was beneficial for the society and the economy—and that it enabled displaced families to reunify and rebuild their lives.

“I think all those principles are, at the very least, being questioned,” Jones-Correa says. He adds that in the U.S. and Europe, “[we] are seeing the rise of these openly anti-immigrant parties that are willing to pay fairly high costs—in the case of the U.K., actually pulling back out of the EU—in order to, as they would put it, regain control of their borders.”

More recently, he has been looking at “immigrants in the suburbs, specifically how suburban native-born Americans respond to immigration,” he says, and at relations among immigrants and the U.S.-born in Philadelphia and Atlanta.

Looking at individual communities can give a bigger picture of the relationships among white and African Americans and migrant groups. A lack of contact among individuals in neighborhoods and workplaces, for example, can lower U.S.-born residents’ tolerance for migrants and lead to support for policies like those hardening the border, restricting immigration into the U.S.

Yet, most Americans do not realize that there has been a net-zero flow of undocumented migration across the U.S. border from Mexico since 2008. And half of all those who are in the U.S. illegally are here because of visa overstays, not because they cross the border without papers.

“A lot of what building a physical wall would do is already accomplished,” says Jones-Correa. He adds that much of the border is already heavily fenced, except in the desert and mountains. This is where people cross over—and where the building of a wall would be, architecturally, a near impossibility.

“Addressing the situation of undocumented workers in ways other than deportation is a policy imperative not just for the undocumented workers themselves, but also for the United States, and the workers’ receiving communities.”

"Crimmigation"

The path to deportation can begin with a minor legal infraction. This is because Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) relies on criminal justice agencies, such police and sheriff’s departments, to identify immigrants for deportation, no matter how minor the crime.

“Mundane violations, such as fishing without a license, running a stop sign while riding a bike, and driving with a broken taillight, have all resulted in undocumented immigrants’ arrest by local police and subsequent removal by federal authorities,” says Amada Armenta, Assistant Professor of Sociology.

In her forthcoming book, Protect, Serve, and Deport: The Rise of Policing as Immigration Enforcement , Armenta analyzes how local police are pivotal actors in the immigration enforcement system although they do not technically enforce immigration laws.

“We call this the ‘crimmigration system’ because it’s a blurring of the line between law enforcement and immigration enforcement,” Armenta says.

In her book, she focuses on the immigrant community in Nashville, Tennessee’s Davidson County. Between 2007 and 2012, the Davidson County Sheriff’s Office participated in an experimental immigration enforcement program called 287(g), which empowered the agency to enforce immigration laws. The sheriff’s employees became de facto immigration officers, screening arrestees for immigration violations. The result? Over 10,000 immigrants were identified for deportation by local authorities. The U.S. government scaled back the program in 2012 because it was deemed ineffective in identifying dangerous criminals for deportation.

“President Trump wants this program not only reinstated but expanded,” Armenta says.

The problem, in her view, is that the broadening of police powers to include deportation erodes the trust between police and the community they serve.

“I study how Latino immigrants perceive safety, and if they feel comfortable reporting crimes of victimization,” she says. “It’s important for the community to feel that they trust the police and vice versa.”

The Other One Percent

The image of the immigrant as a poor person from Mexico who lacks education stands in direct contrast to the reality of the second-largest group of immigrants to the U.S.: Asian Indians. The most educated and highest-income immigrants to the U.S., they began entering the country in number following the 1965 Immigration and Nationality Act (also known as the Hart-Celler Act).

“Seventy percent of Indian immigrants to the U.S. have professional degrees, in comparison to 20 percent of the American population,” says Devesh Kapur, Professor of Political Science, who is the Madan Lal Sobti Professor for the Study of Contemporary India and serves as Director of the Center for the Advanced Study of India.

In his new book, The Other One Percent: Indians in America , he examines the migratory journey of Indian immigrants as well as Americans of Indian descent. The book, co-authored with two of Kapur’s colleagues in the field, has been reviewed in such prestigious periodicals as The Economist and The Financial Times .

“If the U.S. is going to put a cap on migration into the country, what is the optimal mix of legal immigrants in terms of public policy? Those who are young and skilled and ‘fiscally attractive’? Those who are fleeing persecution and come in seeking asylum or as refugees fleeing wars and conflict? Those who are coming in as family reunification or family sponsorship?” Kapur asks. “These are contentious choices and pose difficult trade-offs—and those won’t be easy conversations,” he says.

A Bimodal Trend

Emilio Parrado, Dorothy Swaine Thomas Professor of Sociology, describes immigration to the U.S. as a “bimodal history.” Immigration was high at the end of the 19th and early 20th centuries, declined during the interwar period, and increased again in recent decades. The bimodal trend presents two different images of the U.S.

Chair of the Department of Sociology, Parrado does research focusing on migration, both within and across countries, as a significant life-course event with diverse implications for the migrants themselves, for their families, and for the sending and receiving areas and countries.

“What is it that we look at when we evaluate immigration today?” he asks. “Is it really high, out of control immigration, or is it just back to a more normal level after a decline that ended primarily in the 1980s?” He added, “If we were so successful at incorporating immigrants before, why is Mexican immigration perceived as a burgeoning threat?”

There are two critical issues to consider when discussing immigration from Latin America to the U.S., he explains. The first is the flow of immigrants, the number of people coming in and out of the U.S.; the second is what is called the immigrant “stock,” the foreign-born population residing in the U.S.

We make a “rigid distinction between immigrants and Americans, and between immigrants and U.S. residents, and that distinction is not as clear as one might think,” Parrado explains.

For example, what is the rightful status of children brought into the U.S. as infants, the “DREAMers,” children who have little connection with Mexico as their homeland? The only difference that separates them from U.S. citizens is place of birth, Parrado says. Moreover, as a group they have been very successful at completing high school, attending college, and securing employment.

Deporting them would be not only a terrible outcome for the immigrants themselves, but also a loss of significant human capital for the U.S., Parrado argues.

But the problem is not only for DREAMers. “Addressing the situation of undocumented workers in ways other than deportation is a policy imperative not just for the undocumented workers themselves, but also for the U.S. and the workers’ receiving communities,” he says.

Parrado claims that the revitalization of local areas and cities depends on a dynamic immigrant population. He calls it “disheartening” to see what is happening to the children of immigrants in the U.S. when they and their families are threatened with deportation. He points out that many of those being forced out of the country are the spouses, parents, and children of U.S. citizens.

“Do we really want to tear apart the families of U.S. citizens because we don’t want to regularize the situation of foreign-born workers?” he asks.

Read More from Omnia

Korean-american musicians reflect on their musical journeys.

The event was hosted by the James Joo-Jin Kim Center for Korean Studies in conjunction with the Philadelphia Orchestra, part of the center’s growing focus on community engagement.

Research Roundup: Stable Glass, Shape-Shifting Organisms, and More

The latest installment of this series highlights work from four faculty working in biology, chemistry, and economics.

Gearing Up for Research on Aging

The GEAR UP initiative gives students from underrepresented and disadvantaged backgrounds hands-on experience and mentoring to address a global challenge.

About OMNIA

Editorial Offices

School of Arts & Sciences University of Pennsylvania 3600 Market Street, Suite 300 Philadelphia, PA 19104-3284 Phone: 215-573-4981 Fax: 215-573-2096 Email: [email protected]

Subscribe to the Podcast

- Penn WebLogin

The Great Human Migration

Why humans left their African homeland 80,000 years ago to colonize the world

Guy Gugliotta

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/migrations_jul08_631.jpg)

Seventy-seven thousand years ago, a craftsman sat in a cave in a limestone cliff overlooking the rocky coast of what is now the Indian Ocean. It was a beautiful spot, a workshop with a glorious natural picture window, cooled by a sea breeze in summer, warmed by a small fire in winter. The sandy cliff top above was covered with a white-flowering shrub that one distant day would be known as blombos and give this place the name Blombos Cave.

The man picked up a piece of reddish brown stone about three inches long that he—or she, no one knows—had polished. With a stone point, he etched a geometric design in the flat surface—simple crosshatchings framed by two parallel lines with a third line down the middle.

Today the stone offers no clue to its original purpose. It could have been a religious object, an ornament or just an ancient doodle. But to see it is to immediately recognize it as something only a person could have made. Carving the stone was a very human thing to do.

The scratchings on this piece of red ocher mudstone are the oldest known example of an intricate design made by a human being. The ability to create and communicate using such symbols, says Christopher Henshilwood, leader of the team that discovered the stone, is "an unambiguous marker" of modern humans, one of the characteristics that separate us from any other species, living or extinct.

Henshilwood, an archaeologist at Norway's University of Bergen and the University of the Witwatersrand, in South Africa, found the carving on land owned by his grandfather, near the southern tip of the African continent. Over the years, he had identified and excavated nine sites on the property, none more than 6,500 years old, and was not at first interested in this cliffside cave a few miles from the South African town of Still Bay. What he would find there, however, would change the way scientists think about the evolution of modern humans and the factors that triggered perhaps the most important event in human prehistory, when Homo sapiens left their African homeland to colonize the world.

This great migration brought our species to a position of world dominance that it has never relinquished and signaled the extinction of whatever competitors remained—Neanderthals in Europe and Asia, some scattered pockets of Homo erectus in the Far East and, if scholars ultimately decide they are in fact a separate species, some diminutive people from the Indonesian island of Flores (see "Were 'Hobbits' Human?"). When the migration was complete, Homo sapiens was the last—and only—man standing.

Even today researchers argue about what separates modern humans from other, extinct hominids. Generally speaking, moderns tend to be a slimmer, taller breed: "gracile," in scientific parlance, rather than "robust," like the heavy-boned Neanderthals, their contemporaries for perhaps 15,000 years in ice age Eurasia. The modern and Neanderthal brains were about the same size, but their skulls were shaped differently: the newcomers' skulls were flatter in back than the Neanderthals', and they had prominent jaws and a straight forehead without heavy brow ridges. Lighter bodies may have meant that modern humans needed less food, giving them a competitive advantage during hard times.

The moderns' behaviors were also different. Neanderthals made tools, but they worked with chunky flakes struck from large stones. Modern humans' stone tools and weapons usually featured elongated, standardized, finely crafted blades. Both species hunted and killed the same large mammals, including deer, horses, bison and wild cattle. But moderns' sophisticated weaponry, such as throwing spears with a variety of carefully wrought stone, bone and antler tips, made them more successful. And the tools may have kept them relatively safe; fossil evidence shows Neanderthals suffered grievous injuries, such as gorings and bone breaks, probably from hunting at close quarters with short, stone-tipped pikes and stabbing spears. Both species had rituals—Neanderthals buried their dead—and both made ornaments and jewelry. But the moderns produced their artifacts with a frequency and expertise that Neanderthals never matched. And Neanderthals, as far as we know, had nothing like the etching at Blombos Cave, let alone the bone carvings, ivory flutes and, ultimately, the mesmerizing cave paintings and rock art that modern humans left as snapshots of their world.

When the study of human origins intensified in the 20th century, two main theories emerged to explain the archaeological and fossil record: one, known as the multi-regional hypothesis, suggested that a species of human ancestor dispersed throughout the globe, and modern humans evolved from this predecessor in several different locations. The other, out-of-Africa theory, held that modern humans evolved in Africa for many thousands of years before they spread throughout the rest of the world.

In the 1980s, new tools completely changed the kinds of questions that scientists could answer about the past. By analyzing DNA in living human populations, geneticists could trace lineages backward in time. These analyses have provided key support for the out-of-Africa theory. Homo sapiens , this new evidence has repeatedly shown, evolved in Africa, probably around 200,000 years ago.

The first DNA studies of human evolution didn't use the DNA in a cell's nucleus—chromosomes inherited from both father and mother—but a shorter strand of DNA contained in the mitochondria, which are energy-producing structures inside most cells. Mitochondrial DNA is inherited only from the mother. Conveniently for scientists, mitochondrial DNA has a relatively high mutation rate, and mutations are carried along in subsequent generations. By comparing mutations in mitochondrial DNA among today's populations, and making assumptions about how frequently they occurred, scientists can walk the genetic code backward through generations, combining lineages in ever larger, earlier branches until they reach the evolutionary trunk.

At that point in human history, which scientists have calculated to be about 200,000 years ago, a woman existed whose mitochondrial DNA was the source of the mitochondrial DNA in every person alive today. That is, all of us are her descendants. Scientists call her "Eve." This is something of a misnomer, for Eve was neither the first modern human nor the only woman alive 200,000 years ago. But she did live at a time when the modern human population was small—about 10,000 people, according to one estimate. She is the only woman from that time to have an unbroken lineage of daughters, though she is neither our only ancestor nor our oldest ancestor. She is, instead, simply our "most recent common ancestor," at least when it comes to mitochondria. And Eve, mitochondrial DNA backtracking showed, lived in Africa.

Subsequent, more sophisticated analyses using DNA from the nucleus of cells have confirmed these findings, most recently in a study this year comparing nuclear DNA from 938 people from 51 parts of the world. This research, the most comprehensive to date, traced our common ancestor to Africa and clarified the ancestries of several populations in Europe and the Middle East.

While DNA studies have revolutionized the field of paleoanthropology, the story "is not as straightforward as people think," says University of Pennsylvania geneticist Sarah A. Tishkoff. If the rates of mutation, which are largely inferred, are not accurate, the migration timetable could be off by thousands of years.

To piece together humankind's great migration, scientists blend DNA analysis with archaeological and fossil evidence to try to create a coherent whole—no easy task. A disproportionate number of artifacts and fossils are from Europe—where researchers have been finding sites for well over 100 years—but there are huge gaps elsewhere. "Outside the Near East there is almost nothing from Asia, maybe ten dots you could put on a map," says Texas A&M University anthropologist Ted Goebel.

As the gaps are filled, the story is likely to change, but in broad outline, today's scientists believe that from their beginnings in Africa, the modern humans went first to Asia between 80,000 and 60,000 years ago. By 45,000 years ago, or possibly earlier, they had settled Indonesia, Papua New Guinea and Australia. The moderns entered Europe around 40,000 years ago, probably via two routes: from Turkey along the Danube corridor into eastern Europe, and along the Mediterranean coast. By 35,000 years ago, they were firmly established in most of the Old World. The Neanderthals, forced into mountain strongholds in Croatia, the Iberian Peninsula, the Crimea and elsewhere, would become extinct 25,000 years ago. Finally, around 15,000 years ago, humans crossed from Asia to North America and from there to South America.

Africa is relatively rich in the fossils of human ancestors who lived millions of years ago (see timeline, opposite). Lush, tropical lake country at the dawn of human evolution provided one congenial living habitat for such hominids as Australopithecus afarensis . Many such places are dry today, which makes for a congenial exploration habitat for paleontologists. Wind erosion exposes old bones that were covered in muck millions of years ago. Remains of early Homo sapiens , by contrast, are rare, not only in Africa, but also in Europe. One suspicion is that the early moderns on both continents did not—in contrast to Neanderthals—bury their dead, but either cremated them or left them to decompose in the open.

In 2003, a team of anthropologists reported the discovery of three unusual skulls—two adults and a child—at Herto, near the site of an ancient freshwater lake in northeast Ethiopia. The skulls were between 154,000 and 160,000 years old and had modern characteristics, but with some archaic features. "Even now I'm a little hesitant to call them anatomically modern," says team leader Tim White, from the University of California at Berkeley. "These are big, robust people, who haven't quite evolved into modern humans. Yet they are so close you wouldn't want to give them a different species name."

The Herto skulls fit with the DNA analysis suggesting that modern humans evolved some 200,000 years ago. But they also raised questions. There were no other skeletal remains at the site (although there was evidence of butchered hippopotamuses), and all three skulls, which were nearly complete except for jawbones, showed cut marks—signs of scraping with stone tools. It appeared that the skulls had been deliberately detached from their skeletons and defleshed. In fact, part of the child's skull was highly polished. "It is hard to argue that this is not some kind of mortuary ritual," White says.

Even more provocative were discoveries reported last year. In a cave at Pinnacle Point in South Africa, a team led by Arizona State University paleoanthropologist Curtis Marean found evidence that humans 164,000 years ago were eating shellfish, making complex tools and using red ocher pigment—all modern human behaviors. The shellfish remains—of mussels, periwinkles, barnacles and other mollusks—indicated that humans were exploiting the sea as a food source at least 40,000 years earlier than previously thought.

The first archaeological evidence of a human migration out of Africa was found in the caves of Qafzeh and Skhul, in present-day Israel. These sites, initially discovered in the 1930s, contained the remains of at least 11 modern humans. Most appeared to have been ritually buried. Artifacts at the site, however, were simple: hand axes and other Neanderthal-style tools.

At first, the skeletons were thought to be 50,000 years old—modern humans who had settled in the Levant on their way to Europe. But in 1989, new dating techniques showed them to be 90,000 to 100,000 years old, the oldest modern human remains ever found outside Africa. But this excursion appears to be a dead end: there is no evidence that these moderns survived for long, much less went on to colonize any other parts of the globe. They are therefore not considered to be a part of the migration that followed 10,000 or 20,000 years later.

Intriguingly, 70,000-year-old Neanderthal remains have been found in the same region. The moderns, it would appear, arrived first, only to move on, die off because of disease or natural catastrophe or—possibly—get wiped out. If they shared territory with Neanderthals, the more "robust" species may have outcompeted them here. "You may be anatomically modern and display modern behaviors," says paleoanthropologist Nicholas J. Conard of Germany's University of Tübingen, "but apparently it wasn't enough. At that point the two species are on pretty equal footing." It was also at this point in history, scientists concluded, that the Africans ceded Asia to the Neanderthals.

Then, about 80,000 years ago, says Blombos archaeologist Henshilwood, modern humans entered a "dynamic period" of innovation. The evidence comes from such South African cave sites as Blombos, Klasies River, Diepkloof and Sibudu. In addition to the ocher carving, the Blombos Cave yielded perforated ornamental shell beads—among the world's first known jewelry. Pieces of inscribed ostrich eggshell turned up at Diepkloof. Hafted points at Sibudu and elsewhere hint that the moderns of southern Africa used throwing spears and arrows. Fine-grained stone needed for careful workmanship had been transported from up to 18 miles away, which suggests they had some sort of trade. Bones at several South African sites showed that humans were killing eland, springbok and even seals. At Klasies River, traces of burned vegetation suggest that the ancient hunter-gatherers may have figured out that by clearing land, they could encourage quicker growth of edible roots and tubers. The sophisticated bone tool and stoneworking technologies at these sites were all from roughly the same time period—between 75,000 and 55,000 years ago.

Virtually all of these sites had piles of seashells. Together with the much older evidence from the cave at Pinnacle Point, the shells suggest that seafood may have served as a nutritional trigger at a crucial point in human history, providing the fatty acids that modern humans needed to fuel their outsize brains: "This is the evolutionary driving force," says University of Cape Town archaeologist John Parkington. "It is sucking people into being more cognitively aware, faster-wired, faster-brained, smarter." Stanford University paleoanthropologist Richard Klein has long argued that a genetic mutation at roughly this point in human history provoked a sudden increase in brainpower, perhaps linked to the onset of speech.

Did new technology, improved nutrition or some genetic mutation allow modern humans to explore the world? Possibly, but other scholars point to more mundane factors that may have contributed to the exodus from Africa. A recent DNA study suggests that massive droughts before the great migration split Africa's modern human population into small, isolated groups and may have even threatened their extinction. Only after the weather improved were the survivors able to reunite, multiply and, in the end, emigrate. Improvements in technology may have helped some of them set out for new territory. Or cold snaps may have lowered sea level and opened new land bridges.

Whatever the reason, the ancient Africans reached a watershed. They were ready to leave, and they did.

DNA evidence suggests the original exodus involved anywhere from 1,000 to 50,000 people. Scientists do not agree on the time of the departure—sometime more recently than 80,000 years ago—or the departure point, but most now appear to be leaning away from the Sinai, once the favored location, and toward a land bridge crossing what today is the Bab el Mandeb Strait separating Djibouti from the Arabian Peninsula at the southern end of the Red Sea. From there, the thinking goes, migrants could have followed a southern route eastward along the coast of the Indian Ocean. "It could have been almost accidental," Henshilwood says, a path of least resistance that did not require adaptations to different climates, topographies or diet. The migrants' path never veered far from the sea, departed from warm weather or failed to provide familiar food, such as shellfish and tropical fruit.

Tools found at Jwalapuram, a 74,000-year-old site in southern India, match those used in Africa from the same period. Anthropologist Michael Petraglia of the University of Cambridge, who led the dig, says that although no human fossils have been found to confirm the presence of modern humans at Jwalapuram, the tools suggest it is the earliest known settlement of modern humans outside of Africa except for the dead enders at Israel's Qafzeh and Skhul sites.

And that's about all the physical evidence there is for tracking the migrants' early progress across Asia. To the south, the fossil and archaeological record is clearer and shows that modern humans reached Australia and Papua New Guinea—then part of the same landmass—at least 45,000 years ago, and maybe much earlier.

But curiously, the early down under colonists apparently did not make sophisticated tools, relying instead on simple Neanderthal-style flaked stones and scrapers. They had few ornaments and little long-distance trade, and left scant evidence that they hunted large marsupial mammals in their new homeland. Of course, they may have used sophisticated wood or bamboo tools that have decayed. But University of Utah anthropologist James F. O'Connell offers another explanation: the early settlers did not bother with sophisticated technologies because they did not need them. That these people were "modern" and innovative is clear: getting to New Guinea-Australia from the mainland required at least one sea voyage of more than 45 miles, an astounding achievement. But once in place, the colonists faced few pressures to innovate or adapt new technologies. In particular, O'Connell notes, there were few people, no shortage of food and no need to compete with an indigenous population like Europe's Neanderthals.

Modern humans eventually made their first forays into Europe only about 40,000 years ago, presumably delayed by relatively cold and inhospitable weather and a less than welcoming Neanderthal population. The conquest of the continent—if that is what it was—is thought to have lasted about 15,000 years, as the last pockets of Neanderthals dwindled to extinction. The European penetration is widely regarded as the decisive event of the great migration, eliminating as it did our last rivals and enabling the moderns to survive there uncontested.

Did modern humans wipe out the competition, absorb them through interbreeding, outthink them or simply stand by while climate, dwindling resources, an epidemic or some other natural phenomenon did the job? Perhaps all of the above. Archaeologists have found little direct evidence of confrontation between the two peoples. Skeletal evidence of possible interbreeding is sparse, contentious and inconclusive. And while interbreeding may well have taken place, recent DNA studies have failed to show any consistent genetic relationship between modern humans and Neanderthals.

"You are always looking for a neat answer, but my feeling is that you should use your imagination," says Harvard University archaeologist Ofer Bar-Yosef. "There may have been positive interaction with the diffusion of technology from one group to the other. Or the modern humans could have killed off the Neanderthals. Or the Neanderthals could have just died out. Instead of subscribing to one hypothesis or two, I see a composite."

Modern humans' next conquest was the New World, which they reached by the Bering Land Bridge—or possibly by boat—at least 15,000 years ago. Some of the oldest unambiguous evidence of humans in the New World is human DNA extracted from coprolites—fossilized feces—found in Oregon and recently carbon dated to 14,300 years ago.

For many years paleontologists still had one gap in their story of how humans conquered the world. They had no human fossils from sub-Saharan Africa from between 15,000 and 70,000 years ago. Because the epoch of the great migration was a blank slate, they could not say for sure that the modern humans who invaded Europe were functionally identical to those who stayed behind in Africa. But one day in 1999, anthropologist Alan Morris of South Africa's University of Cape Town showed Frederick Grine, a visiting colleague from Stony Brook University, an unusual-looking skull on his bookcase. Morris told Grine that the skull had been discovered in the 1950s at Hofmeyr, in South Africa. No other bones had been found near it, and its original resting place had been befouled by river sediment. Any archaeological evidence from the site had been destroyed—the skull was a seemingly useless artifact.

But Grine noticed that the braincase was filled with a carbonate sand matrix. Using a technique unavailable in the 1950s, Grine, Morris and an Oxford University-led team of analysts measured radioactive particles in the matrix. The skull, they learned, was 36,000 years old. Comparing it with skulls from Neanderthals, early modern Europeans and contemporary humans, they discovered it had nothing in common with Neanderthal skulls and only peripheral similarities with any of today's populations. But it matched the early Europeans elegantly. The evidence was clear. Thirty-six thousand years ago, says Morris, before the world's human population differentiated into the mishmash of races and ethnicities that exist today, "We were all Africans."

Get the latest History stories in your inbox?

Click to visit our Privacy Statement .

MA in American History : Apply now and enroll in graduate courses with top historians this summer!

- AP US History Study Guide

- History U: Courses for High School Students

- History School: Summer Enrichment

- Lesson Plans

- Classroom Resources

- Spotlights on Primary Sources

- Professional Development (Academic Year)

- Professional Development (Summer)

- Book Breaks

- Inside the Vault

- Self-Paced Courses

- Browse All Resources

- Search by Issue

- Search by Essay

- Become a Member (Free)

- Monthly Offer (Free for Members)

- Program Information

- Scholarships and Financial Aid

- Applying and Enrolling

- Eligibility (In-Person)

- EduHam Online

- Hamilton Cast Read Alongs

- Official Website

- Press Coverage

- Veterans Legacy Program

- The Declaration at 250

- Black Lives in the Founding Era

- Celebrating American Historical Holidays

- Browse All Programs

- Donate Items to the Collection

- Search Our Catalog

- Research Guides

- Rights and Reproductions

- See Our Documents on Display

- Bring an Exhibition to Your Organization

- Interactive Exhibitions Online

- About the Transcription Program

- Civil War Letters

- Founding Era Newspapers

- College Fellowships in American History

- Scholarly Fellowship Program

- Richard Gilder History Prize

- David McCullough Essay Prize

- Affiliate School Scholarships

- Nominate a Teacher

- Eligibility

- State Winners

- National Winners

- Gilder Lehrman Lincoln Prize

- Gilder Lehrman Military History Prize

- George Washington Prize

- Frederick Douglass Book Prize

- Our Mission and History

- Annual Report

- Contact Information

- Student Advisory Council

- Teacher Advisory Council

- Board of Trustees

- Remembering Richard Gilder

- President's Council

- Scholarly Advisory Board

- Internships

- Our Partners

- Press Releases

History Resources

- Immigration and Migration

by Hasia Diner

- The Development of the West

- Populism and Agrarian Discontent

- The Gilded Age

- Empire Building

The United States emerged in the last third of the nineteenth century as an industrial powerhouse, producing goods that then circulated around the world. People in distant countries used American-made clothes, shoes, textiles, machines, steel, oil, rubber, and tools, among other finished products. They also ate foods grown in American soil and relied upon America’s iron ore, coal, and lumber, all transported from the hinterlands to the great shipping ports by American-built railroads. This frenzy of production transformed the United States in the decades following the Civil War, making it the most dynamic economic engine in the world.

None of this could have happened without a work force that sewed the clothing, dug the coal, forged the steel, operated the railroads, and stoked the fires of the many thousands of factories, mills, mines, and workshops that spread over the United States. The industrialization of America stimulated the vast expansion of its own domestic business and agricultural sectors as well. Workers in factories and mines needed food, housing, and a range of consumer goods. As factory employment grew and the population expanded, businesses responded by selling their wares to the workers, enabling them to then go out and work and keep the economy on its course. Not limited to the Northeast, which had been the center of industry earlier in the nineteenth century, industrialization transformed America, in no small measure as a result of massive immigration.

Those newcomers came primarily from Europe and constituted the bulk of the laborers who made industrialization possible. Statistics tell part of the story. In the decade from 1871 until 1880 more than 2,800,000 arrived, while the following ten-year period brought in over 5,000,000. In the subsequent two decades well over thirteen million arrived, with the period from 1901 to 1910 being the single largest decade of immigration. Clearly with numbers like this immigration was a serious issue in American life and became the focus of much political debate and contention. These numbers have to be thought of in percentage terms as well. As a point of contrast, in 1850, the foreign born made up 9.7 percent of the American population; by 1890 that figure stood at 14.7 percent.

The story of immigration to the United States in the industrial era also should be thought of in terms of where the immigrants came from. In the 1870s migration tended to come primarily from central and northern Europe, the countries of Scandinavia, Germany, England, Ireland (which although part of Great Britain had a unique and separate immigration history), and the Austro-Hungarian Empire. By 1900 migration gradually shifted to the east and the south and most immigrants hailed from Italy, the Czarist empire, Roumania, and other places in southern and eastern Europe. Catholics predominated, with a significant influx of Eastern Orthodox also adding to America’s religious diversity. Immigration of the industrial era also saw the size of America’s Jewish population grow exponentially. In 1870 about 250,000 Jews lived in the United States, but the new migration that extended into the 1920s brought in an additional 3,000,000 Jews.

Not only Europeans made their way to the United States in these decades. Immigrants from Mexico, even from its more remote regions, began to arrive in the late nineteenth century, primarily to work on the railroads, and they created small enclaves as far north as Chicago before the beginning of the twentieth century. Women and men from Syria and Lebanon, mostly Christians, also arrived in the latter part of the nineteenth century. Few of them flocked to industrial work, but as peddlers and small shopkeepers they provided consumer goods to industrial workers and farmers, both native born and immigrant. Immigrants from the Punjab region, primarily Sikhs, arrived in the Pacific Northwest in the late 1800s as well, and they joined railroad crews and logging camps. Some became farmers. Small numbers of immigrants also came from the Philippines, Japan, and various islands of the Caribbean.

The two largest non-European immigrant groups in this period included French Canadians, streaming south into New England from Quebec and the Maritime Provinces, and the Chinese. The two groups resembled each other in some ways. They each gravitated to a specific geographic region in the United States, the former to New England with its textile industry and the latter to California, and formed visible ethnic enclaves. But they had very different histories in the United States. French Canadian immigration was never restricted and even after the imposition of quotas in the 1920s, they could come and go as they chose across a largely porous border.

The Chinese story followed a very different course. The Chinese in fact were the only immigrants to ever be excluded specifically by nationality. When Congress enacted across-the-board immigration restriction in the 1920s, it did not exclude any one group. When Japanese immigration came to an end in 1908, it happened through a diplomatic agreement known as the Gentlemen’s Agreement.

The history of the Chinese stands in a class of its own. Between the end of the Civil War and 1882, about 300,000 Chinese immigrants had entered the United States. Anti-Chinese sentiment had been running high in California since the 1850s, and in 1882 the United States Congress passed the first piece of immigration restriction, of any kind, in the history of the nation. The Chinese Exclusion Act barred Chinese immigrants from coming to the United States, although there were a few exempted categories, including students, merchants, and the children of naturalized citizens. The imposition of such a restriction ushered in a new era in American history, one in which the federal government moved, slowly, toward curtailing the uncapped flood of newcomers from abroad.

To many native-born Americans the influx of so many millions of foreigners, mostly Catholics and Jews, and most relatively poor and speakers of myriad languages, seemed threatening to the way of life they considered authentically American. A quick summary of the major developments of the years from the middle of the 1870s until 1900 shows how much the concern over immigration came to dominate national politics.

The trend toward government action vis-à-vis immigration may be said to have started with a US Supreme Court case in 1875, Henderson v. the Mayor of New York , as the opening salvo in a debate that raged in America over immigration. In that case the Court ruled that the various states could not regulate immigration individually from abroad as they chose, but that this power lay in the hands of Congress. Thus, the long-established practice of leaving immigration to the states it was overturned. Congress soon passed the first act of restriction, banning convicts and prostitutes from entering the United States. The first, and only, restriction of a specific group on the basis or national origin or race came in 1882 with the passage of a temporary Chinese Exclusion Act, which became permanent in 1900 by congressional act. In 1885 Congress passed the Foran Act, which prohibited the migration of contract labor, that is, women and men hired abroad and whose fare had been paid by an American employer. In order for these restrictions and regulations to work Congress had to create a bureaucracy and in 1891, under the aegis of the Treasury Department, it founded the Bureau of Immigration. So, too, in 1892 the immigrant-receiving station at Ellis Island opened its doors (with smaller stations in Boston, Philadelphia, Baltimore, New Orleans, Galveston, and San Francisco) making visible the regulatory process.

The 1890s saw not only the march toward regulation coordinated by the government, but also the emergence of organized citizen action against immigration. In 1895 a group of elite women and men in Boston founded the Immigration Restriction League with the goal of preserving the historic ethnic make-up of America—as defined by this group. They pushed for a literacy test, which passed in Congress in 1896, although President Grover Cleveland vetoed the measure. In the early twentieth century during the presidency of Theodore Roosevelt, a few more categories of potential immigrants got added to the list of the undesirables, including the "feeble-minded," "imbeciles," carriers of various diseases, and anarchists.

This last category, anarchists, had a very specific origin, and tells us much about the rise of industrial America. In 1901 Leon Czolgosz, the son of immigrants and an anarchist, assassinated President William McKinley. This shocking event stoked American fears about political turbulence and radicalism, which they saw as a threat to the basic stability of the nation, and one associated with foreigners. As more and more Americans worked for industrial employers who could force their employees to endure whatever conditions the boss wanted, at whatever rate of pay the market could bear, more and more workers sought forms of action and organization to address their plight.

One event from each decade of this era can demonstrate the escalation of labor and radical action. In 1877—dubbed "the year of violence"—tens of thousands of workers in Pennsylvania, Ohio, Maryland, West Virginia, and elsewhere shut down the rail system for more than forty days in the Great Railway Strike. Local police across the strike regions used force to quell the strikes, and President Rutherford B. Hayes called in the Army to assist in this effort. A decade later, on May 4, 1886, a gathering in Haymarket Square in Chicago ended when a bomb was tossed into a group of police officers trying to break up the crowd. The police fired into the crowd and in the process created a group of martyrs to the cause of labor. In 1892 a strike at the Homestead, Pennsylvania, steel mills of Carnegie Steel pitted the police and armed Pinkerton detectives against workers who had taken over the plant.

While immigrants alone did not participate in these strikes and in the labor and radical movements, many Americans in fact equated the two, and growing numbers of them and their political representatives were convinced that continued immigration harmed the country, threatening the coherence and stability of the nation.

Not all Americans, however, put the blame on the immigrants; some saw unbridled capitalism as the source of the social unrest. While some in the Progressive movement harbored anti-immigrant sentiment, many in the movement believed that the fault lay with the system and not with the women and men who had come to the United States to make a living and who fueled the nation’s industrial output and made its wealth possible.

In 1890 a New York journalist, himself an immigrant from Denmark, Jacob Riis, castigated the greed of landlords and employers for immiserating the lives of the city’s cigar workers, garment shop employees, and other laborers. His expose How the Other Half Lives , on conditions among the poor in New York City, complete with photographs, was widely read and led to legislative action in New York . A year earlier two women in Chicago, Jane Addams and Ellen Gates Starr, had opened up a settlement house, Hull House, in the packinghouse district where large numbers of Polish, Italian, and eastern European Jews lived and labored. Starr and Addams experimented with various ways to both improve the lives of the immigrant poor and advocate for them. Settlement houses like Hull House sprang up in Boston, Baltimore, New York, Buffalo, Milwaukee, and in all the large cities to which immigrants had gone, drawn by the magnet of the jobs available in American industry. Those immigrant workers and the others across the country played a pivotal role in providing the labor necessary to create industrial America.

Hasia Diner is the Paul S. and Sylvia Steinberg Professor of American Jewish History and director of the Goldstein-Goren Center for American Jewish History at New York University. Among her publications are From Arrival to Incorporation: Migrants to the US in a Global Age (2007) and We Remember with Reverence and Love: American Jews and the Myth of Silence after the Holocaust, 1945–1962 (2009).

Stay up to date, and subscribe to our quarterly newsletter.

Learn how the Institute impacts history education through our work guiding teachers, energizing students, and supporting research.

An Introduction to Migration Studies: The Rise and Coming of Age of a Research Field

- Open Access

- First Online: 04 June 2022

Cite this chapter

You have full access to this open access chapter

- Peter Scholten 2 ,

- Asya Pisarevskaya 3 &

- Nathan Levy 3

Part of the book series: IMISCOE Research Series ((IMIS))

29k Accesses

5 Citations

1 Altmetric

Migration studies has contributed significantly to our understanding of mobilities and migration-related diversities. It has developed a distinct body of knowledge on why people migrate, how migration takes place, and what the consequences are of migration in a broad sense, both for migrants themselves and for societies involved in migration. As a broadly-based research field, migration studies has evolved at the crossroads of a variety of disciplines. This includes disciplines such as sociology, political science, anthropology, geography, law and economics, but increasingly it expands to a broader pool of disciplines also including health studies, development studies, governance studies and many more, building on insights from these disciplines.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Changing Perspectives on Migration History and Research in Switzerland: An Introduction

15 Internal Migration

Introduction: Contemporary Insights on Migration and Population Distribution

Migration is itself in no way a new phenomenon; but the specific and interdisciplinary study of migration is relatively recent. Although the genesis of migration studies goes back to studies in the early twentieth century, it was only by the end of the twentieth and the beginning of the twenty-first century that the number of specialised master programmes in migration studies increased, that the number of journal outlets grew significantly, that numerous specialised research groups and institutes emerged all over the world, and that in broader academia migration studies was recognised as a distinct research field in its own right. By 2018 there were at least 45 specialised journals in migration studies (Pisarevskaya et al., 2019 , p. 462). The field has developed its own international research networks, such as IMISCOE (International Migration, Integration and Social Cohesion in Europe), NOMRA (Network of Migration Research on Africa), and the global more policy-oriented network Metropolis. Students at an increasingly broad range of universities can study dedicated programs as well as courses on migration studies. Slowly but gradually the field is also globalising beyond its European and North American roots.

Migration studies is a research field, which means that it is not a discipline in itself with a core body of knowledge that applies to various topics, but an area of studies that focus on a specific topic while building on insights from across various disciplines. It has clear roots in particular in economics, geography, anthropology and sociology. However, when looking at migration publications and conferences today, the disciplinary diversity of the field has increased significantly, for instancing bringing important contributions from and to political sciences, law, demography, cultural studies, languages, history, health studies and many more. It is hard to imagine a discipline to which migration studies is not relevant; for instance, even for engineering studies, migration has become a topic of importance when focusing on the role that social media play as migration infrastructures. Beyond being multidisciplinary (combining insights from various disciplines), the field has become increasing interdisciplinary (with its own approach that combines aspects from various disciplines) or even transdisciplinary (with an approach that systematically integrates knowledge and methods from various disciplines).

1 A Pluralist Perspective on Migration Studies

Migration studies is a broad and diverse research field that covers many different topics, ranging from the economics of migration to studies of race and ethnicity. As with many research fields, the boundaries of the field cannot be demarcated very clearly. However, this diversity does also involve a fair degree of fragmentation in the field. For instance, the field features numerous sub-fields of study, such as refugee studies, multicultural studies, race studies, diversity studies, etc. In fact, there are many networks and conferences within the field with a specific focus, for instance, on migration and development. So, the field of migration studies also encompasses, in itself, a broad range of subfields.

This diversity is not only reflected in the topics covered by migration studies, but also in theoretical and methodological approaches. It is an inherently pluralistic field, bringing often fundamentally different theoretical perspectives on key topics such as the root causes of integration. It brings very different methods, for instance ranging from ethnographic fieldwork with specific migrant communities to large-n quantitative analyses of the relation between economics and migration.

Therefore, this book is an effort to capture and reflect on this pluralistic character of field. It resists the temptation to bring together a ‘state of the art’ of knowledge on topics, raising the illusion that there is perhaps a high degree of knowledge consensus. Rather, we aim to bring to the foreground the key theoretical and methodological discussions within the field, and let the reader appreciate the diversity and richness of the field.

However, the book will also discuss how this pluralism can complicate discussions within the field based on very basic concepts. Migration studies stands out from most other research fields in terms of a relatively high degree of contestation of some of its most basic concepts. Examples include terms as ‘integration’, ‘multiculturalism’, ‘cohesion’ but perhaps most pertinent also the basic concept of ‘migration.’ Many of the field’s basic concepts can be defined as essentially contested concepts. Without presuming to bring these conceptual discussions to a close, this book does bring an effort to map and understand these discussions, aiming to prevent conceptual divides from leading to fragmentation in the field.

This conceptual contestation reflects broader points on how the field has evolved. Various studies have shown that the field’s development in various countries and at various moments has been spurred by a policy context in which migration was problematised. Many governments revealed a clear interest in research that could help governments control migration and promote the ‘integration’ of migrants into their nation-states (DeWind, 2000 ). The field’s strong policy relevance also led to a powerful dynamic of coproduction in specific concepts such as ‘integration’ or ‘migrant.’ At the same time, there is also clear critical self-reflection in the field on such developments, and on how to promote more systematic theory building in migration studies. This increase of reflexivity can be taken as a sign of the coming of age of migration studies as a self-critical and self-conscious research field.

An introduction to migration studies will need to combine a systematic approach to mapping the field with a strong historical awareness of how the field has developed and how specific topics, concepts and methods have emerged. Therefore, in this chapter, we will do just that. We will start with a historical analysis of how the field emerged and evolved, in an effort to show how the field became so diverse and what may have been critical junctures in the development of the field. Subsequently, we will try to define what is migration studies, by a systematic approach towards mapping the pluralism of the field without losing grip of what keeps together the field of migration studies. Therefore, rather than providing one sharp definition of migration studies, we will map that parts that together are considered to constitute migration studies. Finally, we will map the current state of the research field.

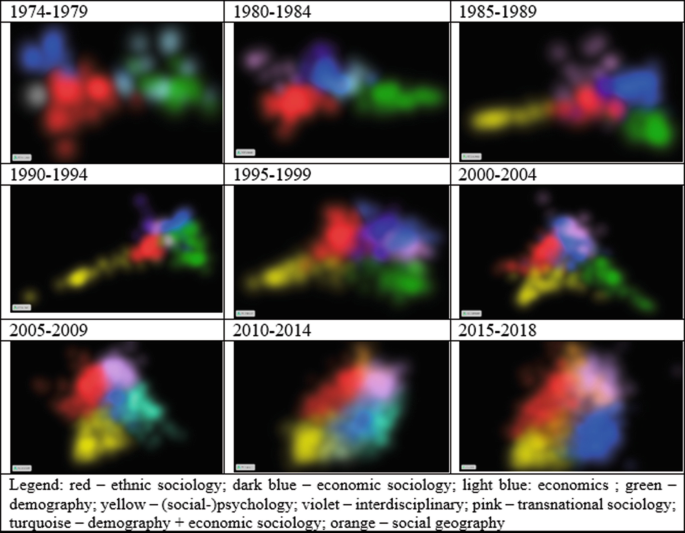

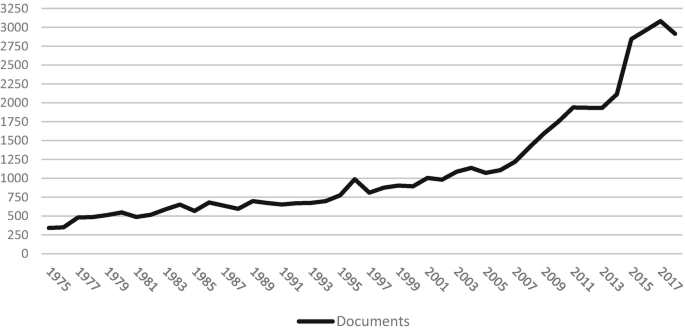

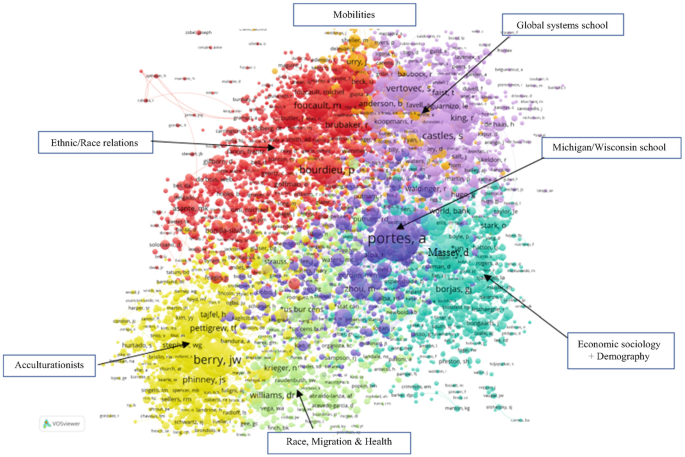

To provide a comprehensive overview of such a pluralist and complex field of study, we employ a variety of methods. Qualitative historical analysis of key works that shaped the formation and development of the field over the years is combined with novel bibliometric methods to give a birds-eye view of the structure of the field in terms of volume of publications, internationalisation and epistemic communities of scholarship on migration. The bibliometric analysis presented in this chapter is based on our previous articles, in which we either, used Scopus data from 40 key journals (Pisarevskaya et al., 2019 , or a complex key-word query to harvest meta-data of relevant publications from Web of Science (Levy et al., 2020 ). Both these approaches to meta-data collection were created and reviewed with the help of multiple experts of migration studies. You can consult the original publications for more details. Our meta-data contained information on authors, years of publication, journals, titles, and abstracts of articles and books, as well as reference lists, i.e. works that were cited by each document in the dataset.

In this chapter you will see the findings from these analyses, revealing the growth trends of migration specific journals, and yearly numbers of articles published on migration-related topics, number and geographical distribution of international co-authorships, as well as referencing patterns of books and articles – the “co-citation analysis”. The colourful network graphs you will see later in the chapter, reveal links between scholars, whose writings are mentioned together in one reference list. When authors are often mentioned together in the publications of other scientists, it means that their ideas are part of a common conversation. The works of the most-cited authors in different parts of the co-citation networks give us an understanding of which topics they specialise in, which methods they use in their research, and also within which disciplinary traditions they work. All in all, co-citation analysis provides an insight on the conceptual development of epistemic communities with their distinct paradigms, methods and thematic foci.

In addition, we bring in some findings from the Migration Research Hub, which hosts an unprecedented number of articles, book chapters, reports, dissertation relevant to the field. All these items are brought together with the help of IT technologies, integration with different databases such as Dimensions, ORCID, Crossref, and Web of Science, as well as submitted by the authors themselves. At the end of 2020, this database contains around 90,000 of items categorised into the taxonomy of migration studies, which will be presented below.

2 What Is Migration Studies?

The historical development of migration studies, as described in the next section, reveals the plurality of the research field. Various efforts to come up with a definition of the field therefore also reflect this plurality. For instance, King ( 2012 ) speaks of migration studies as encompassing ‘all types of international and internal migration, migrants, and migration-related diversities’. This builds on Cohen’s ( 1996 , p. xi–xii) nine conceptual ‘dyads’ in the field. Many of these have since been problematised – answering Cohen’s own call for critical and systematic considerations – but they nonetheless provide a skeletal overview of the field as it is broadly understood and unfolded in this book and in the taxonomy on which it is based:

Individual vs. contextual reasons to migrate

Rate vs. incidence

Internal vs. international migration

Temporary vs. permanent migration

Settler vs. labour migration

Planned vs. flight migration

Economic migrants vs. political refugees

Illegal vs. legal migration

Push vs. pull factors

Therefore, the taxonomy provides the topical structure—elaborated below—by which we approach this book. We do not aim to provide a be-all and end-all definition of migration studies but rather seek to capture its inherent plurality by bringing together chapters which provide a state-of-the-art of different meta-topics within the field.

The taxonomy of migration studies was developed as part of a broader research project, led by IMISCOE, from 2018 to 2020 aimed at comprehensively taking stock of and providing an index for the field (see the Migration Research Hub on www.migrationresearch.com ). It was a community endeavour, involving contributors from multiple methodological, disciplinary, and geographical backgrounds at several stages from beginning to end.

It was built through a combination of two methods. First, the taxonomy is based on a large-scale computer-based inductive analysis of a vast number—over 23,000—of journal articles, chapters, and books from the field of migration studies. This led to an empirical clustering of topics addressed within the dataset, as identified empirically in terms of keywords that tend to go together within specific publications.

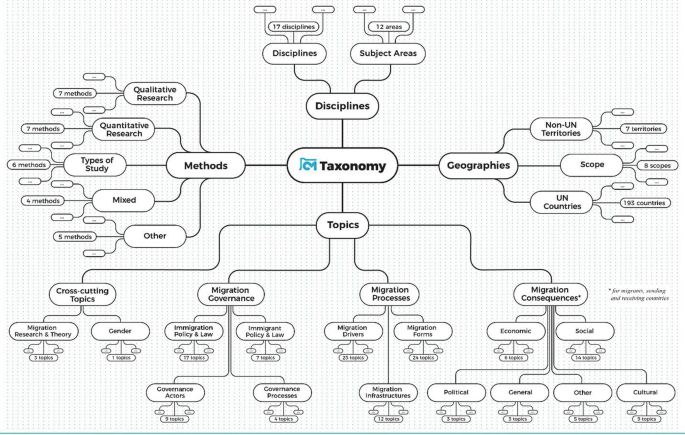

Secondly, this empirical clustering was combined with a deductive approach with the aim of giving logical structure to the inductively developed topics. Engaging, at this stage, with several migration scholars with specific expertise facilitated a theory-driven expansion of the taxonomy towards what it is today, with its hierarchical categorisation not only of topics and sub-categories of topics, but also of methods, disciplines, and geographical focuses (see Fig. 1.1 below).

The structure of the taxonomy of migration studies

In terms of its content, the taxonomy that has been developed distinguishes various meta-topics within migration studies. These include:

Why do people migrate ? This involves a variety of root causes of migration, or migration drivers.

How do people migrate ? This includes a discussion of migration trajectories but also infrastructures of migration.

What forms of migration can be distinguished ? This involves an analytical distinction of a variety of migration forms

What are major consequences of migration , and whom do these consequences concern? This includes a variety of contributions on the broader consequences of migration, including migration-related diversities, ethnicity, race, the relation between migration and the city, the relation between migration and cities, gendered aspects of migration, and migration and development.

How can migration be governed ? This part will cover research on migration policies and broader policies on migration-related diversities, as well as the relation between migration and citizenship.

What methods are used in migration studies ?

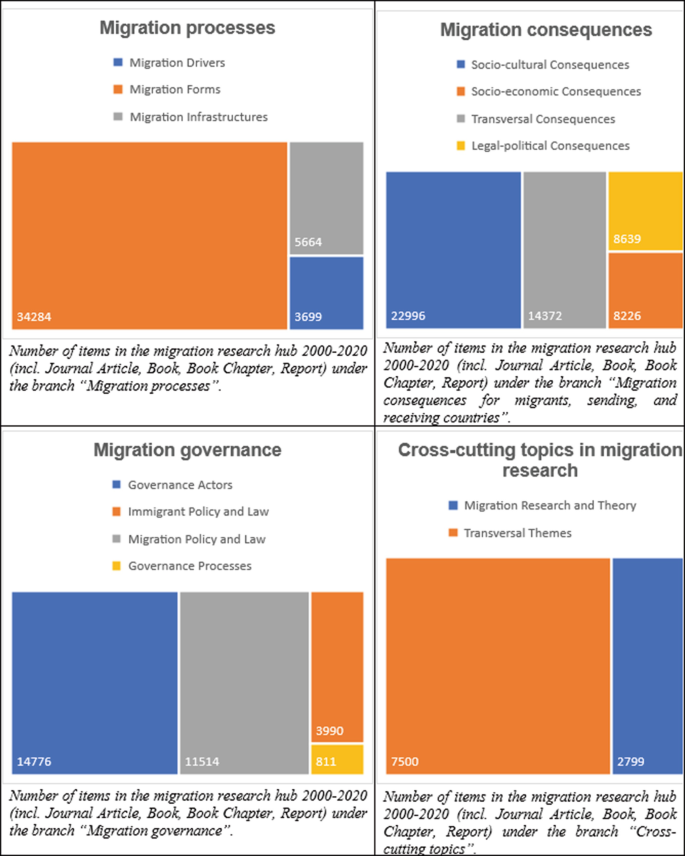

All the topics in the taxonomy are grouped into several branches: Migration processes, Migration Consequences, Migration governance and Cross-cutting. In Fig. 1.2 below you can see how many journal articles, books, book chapters and reports can be found in the migration research hub just for the period of the last 20 years. The number of items belonging to each theme can vary significantly, because some of them are broader than others. Broader themes can be related to larger numbers of items, for instance ‘migration forms’ is very broad, because it includes many types and forms of migration on which scientific research in this field chooses to focus on. On the contrary, the theme of ‘governance processes’ is narrower because less studies are concerned with specific processes of migration management, such as criminalisation, externalisation or implementation.

Distribution of taxonomy branches in the Migration Research Hub

The various chapters in this book can of course never fully represent the full scope of the field. Therefore, the chapters will include various interactive links with the broader literature. This literature is made accessible via the Migration Research Hub, which aims to represent the full scope of migration studies. The Hub is based on the taxonomy and provides a full overview of relevant literature (articles, chapters, books, reports, policy briefs) per taxonomy item. This not only includes works published in migration journals or migration books, but also a broader range of publications, such as disciplinary journals.

Because the Hub is being constantly updated, the taxonomy—along with how we approach the question of ‘what is migration studies?’ in this book—is interactive; it is not dogmatic, but reflexive. As theory develops, new topics and nomenclature emerge. In fact, several topics have been added and some topics have been renamed since “Taxonomy 1.0” was launched in 2018. In this way, the taxonomy is not a fixed entity, but constantly evolving, as a reflection of the field itself.

3 The Historical Development of Migration Studies

3.1 an historical perspective on “migration studies”.

A pluralist perspective on an evolving research field, therefore, cannot rely on one single definition of what constitutes that research field. Instead, a historical perspective can shed light on how “migration studies” has developed. Therefore, we use this introductory chapter to outline the genesis and emergence of what is nowadays considered to be the field of migration studies. This historical perspective will also rely on various earlier efforts to map the development of the field, which have often had a significant influence on what came to be considered “ migration studies ”.

3.2 Genesis of Migration Studies

Migration studies is often recognised as having originated in the work of geographer Ernst Ravenstein in the 1880s, and his 11 Laws of Migration ( 1885 ). These laws were the first effort towards theorising why (internal) migration takes place and what different dynamics of mobility look like, related, for instance, to what happens to the sending context after migrants leave, or differing tendencies between men and women to migrate. Ravenstein’s work provided the foundation for early, primarily economic, approaches to the study of migration, or, more specifically, internal or domestic migration (see Greenwood & Hunt, 2003 ; Massey et al., 1998 ).

The study of international migration and migrants can perhaps be traced back to Znaniecki and Thomas’ ( 1927 ) work on Polish migration to Europe and America. Along with Ravenstein’s Laws , most scholars consider these volumes to mark the genesis of migration studies.

The Polish Peasant and the Chicago School

The Polish Peasant in Europe and America —written by Florian Znaniecki & William Thomas, and first published between 1918 and 1920—contains an in-depth analysis of the lives of Polish migrant families. Poles formed the biggest immigrant group in America at this time. Thomas and Znaniecki’s work was not only seminal for migration research, but for the wider discipline of sociology. Indeed, their colleagues in the Department of Sociology at the University of Chicago, such as Robert Park, had a profound impact on the discipline with their groundbreaking empirical studies of race and ethnic relations (Bulmer, 1986 ; Bommes & Morawska, 2005 ).

Greenwood and Hunt ( 2003 ) provide a helpful overview of the early decades of migration research, albeit through a primarily economic disciplinary lens, with particular focus on America and the UK. According to them, migration research “took off” in the 1930s, catalysed by two societal forces—urbanisation and the Great Depression—and the increased diversity those forces generated. To illustrate this point, they cite the bibliographies collated by Dorothy Thomas ( 1938 ) which listed nearly 200 publications (119 from the USA and UK, 72 from Germany), many of which focused on migration in relation to those two societal forces, in what was already regarded as a “broadly based field of study” (Greenwood & Hunt, 2003 , p. 4).

Prior to Thomas’ bibliography, early indications of the institutionalisation of migration research came in the US, with the establishment of the Social Science Research Council’s Committee on Scientific Aspects of Human Migration (see DeWind, 2000 ). This led to the publication of Thornthwaite’s overview of Internal Migration in the United States ( 1934 ) and one of the first efforts to study migration policymaking, Goodrich et al’s Migration and Economic Opportunity ( 1936 ).

In the case of the UK in the 1930s, Greenwood and Hunt observe an emphasis on establishing formal causal models, inspired by Ravenstein’s Laws . The work of Makower et al. ( 1938 , 1939 , 1940 ), which, like Goodrich, focused on the relationship of migration and unemployment, is highlighted by Greenwood and Hunt as seminal in this regard. The New Palgrave Dictionary of Economics regards Makower and Marschak as having made a “pioneering contribution” to our understanding of labour mobility (see also the several taxonomy topics dealing with labour).

3.3 The Establishment of a Plural Field of Migration Studies (1950s–1980s)

Migration research began to formalise and expand in the 1950s and 1960s (Greenwood & Hunt, 2003 ; Pedraza-Bailey, 1990 ). A noteworthy turning point for the field was the debate around assimilation which gathered pace throughout the 1950s and is perhaps most notably exemplified by Gordon’s ( 1964 ) typology of this concept.

Gordon’s Assimilation Typology and the Problematisation of Integration

Assimilation, integration, acculturation, and the question of how migrants adapt and are incorporated into a host society (and vice versa), has long been a prominent topic in migration studies.

Gordon ( 1964 ) argued that assimilation was composed of seven aspects of identification with the host society: cultural, structural, martial, identificational, behavioural, attitudinal, and civic. His research marked the beginning of hundreds of publications on this question of how migrants and host societies adapt. The broader discussions with which Gordon interacted evolved into one of the major debates in migration studies.

By the 1990s, understandings of assimilation evolved in several ways. Some argued that process was context- or group-dependent (see Shibutani & Kwan, 1965 ; Alba & Nee, 1997 ). Others recognised that there was not merely one type nor indeed one direction of integration (Berry, 1997 ).

The concept itself has been increasingly problematised since the turn of the century. One prominent example of this is Favell ( 2003 ). Favell’s main argument was that integration as a normative policy goal structured research on migration in Western Europe. Up until then, migration research had reproduced what he saw as nation-state-centred power structures. It is worth reading this alongside Wimmer and Glick Schiller (2003) to situate it in broader contemporary debates, but there is plenty more to read on this topic.

For more on literature around this topic, see Chaps. 19 , 20 , and 21 of this book.

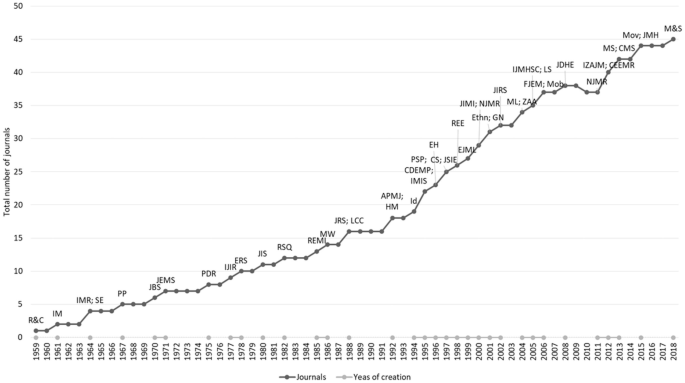

Indeed, these debates and discussions were emblematic of wider shifts in approaches to the study of migration. The first of these was towards the study of international (as opposed to internal) migration in the light of post-War economic dynamics, which also established a split in approaches to migration research that has lasted several decades (see King & Skeldon, 2010 ). The second shift was towards the study of ethnic and race relations, which continued into the 1970s, and was induced by the civil rights movements of these decades (Pedraza-Bailey, 1990 ). These two shifts are reflected in the establishment of some of the earliest journals with a migration and diversity focus in the 1960s—the establishment of journals being an indicator of institutionalisation—as represented in Fig. 1.3 . Among these are journals that continue to be prominent in the field, such as International Migration (1961-), International Migration Review (1964-), and, later, the Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies (1970-) and Ethnic & Racial Studies (1978-).

Number of journals focused on migration and migration-related diversity (1959–2018). (Source: Pisarevskaya et al., 2019 , p. 462) ( R&C Race & Class, IM International Migration, IMR International Migration Review, SE Studi Emigrazione, PP Patterns of Prejudice, JBS Journal of Black Studies, JEMS Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, PDR Population and Development Review, IJIR International Journal of Intercultural Relations, ERS Ethnic & Racial Studies, JIS Journal of Intercultural Studies, RSQ Refugee Survey Quarterly, REMI Revue Européenne des Migrations Internationales, MW Migration World, JRS Journal of Refugee Studies, LCC Language, Culture, and Curriculum, APMJ Asian and Pacific Migration Journal, HM Hommes et Migrations, Id . Identities, PSP Population, Space, and Place, CDEMP Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology, IMIS IMIS-Beitrage, EH Ethnicity & Health, CS Citizenship Studies, JSIE Journal of Studies in International Education, REE Race, Ethnicity, and Education, EJML European Journal of Migration and Law, JIMI Journal of International Migration and Integration, NJMR Norwegian Journal of Migration Research, Ethn . Ethnicities, GN Global Networks, JIRS Journal of Immigrant & Refugee Studies, ML Migration Letters, ZAA Zeitschrift für Ausländerrecht und Ausländerpolitik, IJMHSC International Journal of Migration, Health, and Social Care, LS Latino Studies, FJEM Finnish Journal of Ethnicity and Migration, Mob . Mobilities, JDHE Journal of Diversity in Higher Education, NJMR Nordic Journal of Migration Research (merger of NJMR and FJEM), IZAJM IZA Journal of Migration, CEEMR Central and Eastern European Migration Review, MS Migration Studies, CMS Comparative Migration Studies, Mov . Movements, JMH Journal of Migration History, M&S Migration & Society. For more journals publishing in migration studies, see migrationresearch.com )