Ecological Literacy: Teaching the Next Generation About Sustainable Development

Bioneers Environmental Education Article

As societies search for ways to become more sustainable, Fritjof Capra suggests incorporating the same principles on which nature’s ecosystems operate. In his essay, “Speaking Nature’s Language: Principles for Sustainability” from the book Ecological Literacy , he leaves a blueprint for building a more resilient world on the foundation of natural concepts, such as interdependence and diversity. This essay advocates a shift in thinking to a more holistic view of living systems: taking into account the collective interactions between the parts of the whole, instead of just the parts themselves.

Following is an excerpt from Ecological Literacy by Fritjof Capra, David Orr, Michael Stone and Zenobia Barlow, including an introduction and Capra’s essay.

If anyone has learned to speak nature’s language, it is Fritjof Capra. A founding director of the Center for Ecoliteracy and currently chair of its board, he has distinguished himself over the past forty years as a scientist, systems theorist, and explorer of the philosophical and social ramifications of contemporary science.

Introducing him to an overflow audience at a Bioneers Conference plenary, Kenny Ausubel said, “One of Fritjof Capra’s greatest gifts is his ability to digest enormous amounts of information from highly complex, wide-ranging fields of inquiry. Not only does he explain them elegantly and clearly, but he distills their essence and sees their implications. Because he’s a credentialed scientist who did his time with particle accelerators all over Europe and the United States, Fritjof never overstates his case or lapses into wishful thinking.”

After receiving his Ph.D. in theoretical physics from the University of Vienna in 1966, Capra did research in particle physics at the University of Paris, the University of California at Santa Cruz, the Stanford Linear Accelerator Center, Imperial College of the University of London, and the Lawrence Berkeley Laboratory at the University of California. He also taught at UC Santa Cruz, UC Berkeley, and San Francisco State University.

He is the author of five international bestsellers: The Tao of Physics (1975), The Turning Point (1982), Uncommon Wisdom (1988), The Web of Life (1996), and The Hidden Connections (2002). He coauthored Green Politics (1984), Belonging to the Universe (1991), and EcoManagement (1993), and coedited Steering Business Toward Sustainability (1995).

He is on the faculty of Schumacher College, an international center for ecological studies in England, frequently gives management seminars for top executives, and lectures widely to lay and professional audiences in Europe, Asia, and North and South America. He is an enormously popular speaker, addressing audiences of thousands, switching easily between German, French, English, Italian, and Spanish. The Center for Ecoliteracy’s single greatest source of inquiries is people from as far away as Brazil and India who find the CEL website by linking from Capra’s.

This essay distills thinking that has inspired the Center for Ecoliteracy and served as its intellectual touchstone for a decade.

AS I DISCUSSED IN THE PREFACE to this book, we can design sustainable societies by modeling them after nature’s ecosystems. To understand ecosystems’ principles of organization, which have evolved over billions of years, we need to learn the basic principles of ecology—the language of nature, if you will. The most useful framework for understanding ecology today is the theory of living systems, which is still emerging and whose roots include organismic biology, gestalt psychology, general system theory, and complexity theory (or nonlinear dynamics). For more discussion of the theory of living systems and its implications, please see my book The Hidden Connections .

What is a living system? When we walk out into nature, living systems are what we see. First, every living organism , from the smallest bacterium to all the varieties of plants and animals, including humans, is a living system. Second, the parts of living systems are themselves living systems. A leaf is a living system. A muscle is a living system. Every cell in our bodies is a living system. Third, communities of organisms , including both ecosystems and human social systems such as families, schools, and other human communities, are living systems.

Thinking in terms of complex systems is now at the very forefront of science. It is also very like the ancient thinking that enabled traditional peoples to sustain themselves for thousands of years. But although the modern version of this intellectual tradition is almost a hundred years old, it has still not taken hold in our mainstream culture. I’ve thought quite a lot about why people find systems thinking so difficult and have concluded that there are two main reasons. One is that living systems are nonlinear—they’re networks—while our whole scientific tradition is based on linear thinking—chains of cause and effect.

In linear thinking, when something works, more of the same will always be better. For instance, a “healthy” economy will show strong, indefinite economic growth. But successful living systems are highly nonlinear. They don’t maximize their variables; they optimize them. When something is good, more of the same will not necessarily be better, because things go in cycles, not along straight lines. The point is not to be efficient, but to be sustainable. Quality, not quantity, counts.

We also find systems thinking difficult because we live in a culture that is materialist in both its values and its fundamental worldview. For example, most biologists will tell you that the essence of life lies in the macromolecules— the DNA, proteins, enzymes, and other material structures in living cells. Systems theory tells us that knowledge of these molecules is, of course, very important, but the essence of life does not lie in the molecules. It lies in the patterns and processes through which those molecules interact. You can’t take a photograph of the web of life because it is nonmaterial—a network of relationships.

Perceptual Shifts

Because living systems are nonlinear and rooted in patterns of relationships, understanding the principles of ecology requires a new way of seeing the world and of thinking—in terms of relationships, connectedness, and context —that goes against the grain of traditional Western science and education. Such “contextual” or “systemic” thinking involves several shifts of perception:

From the parts to the whole. Living systems are integrated wholes whose properties cannot be reduced to those of their smaller parts. Their “systemic” properties are properties of the whole that none of the parts has.

From objects to relationships. An ecosystem is not just a collection of species, but is a community. Communities, whether ecosystems or human systems, are characterized by sets, or networks, of relationships. In the systems view, the “objects” of study are networks of relationships, embedded in larger networks. In practice, organizations designed according to this ecological principle are more likely than other organizations to feature relationship-based processes such as cooperation and decision-making by consensus.

From objective knowledge to contextual knowledge. The shift of focus from the parts to the whole implies a shift from analytical thinking to contextual thinking. The properties of the parts are not intrinsic, but can be understood only within the context of the whole. Since explaining things in terms of their contexts means explaining them in terms of their environments, all systems thinking is environmental thinking.

From quantity to quality. Understanding relationships is not easy, especially for those of us educated within a scientific framework, because Western science has always maintained that only the things that can be measured and quantified can be expressed in scientific models. It’s often been implied that phenomena that can be measured and quantified are more important—and maybe even that what cannot be measured and quantified doesn’t exist at all. Relationships and context, however, cannot be put on a scale or measured with a ruler.

From structure to process. Systems develop and evolve. Thus the understanding of living structures is inextricably linked to understanding renewal, change, and transformation.

From contents to patterns. When we draw maps of relationships, we discover certain configurations of relationships that appear again and again. We call these configurations “patterns.” Instead of focusing on what a living system is made of, we study its patterns.

Here we discover a tension between two approaches to the study of nature that has characterized Western science and philosophy throughout the ages. One approach begins with the question: What is it made of? Traditionally, this has been called the study of matter. The other approach begins with the question: What is the pattern? And this, since Greek times, has been called the study of form.

In the West, most of the time, the study of matter has dominated in science. But late in the twentieth century, the study of form came to the fore again, with the emergence of systems thinking. Chaos and complexity theory are essentially theories of patterns. The so-called strange attractors of chaos theory are visual patterns that represent the dynamics of a certain chaotic system. The fractals of fractal geometry are visual patterns. In fact, the whole new mathematics of complexity is essentially the mathematics of patterns.

Some Implications for Education

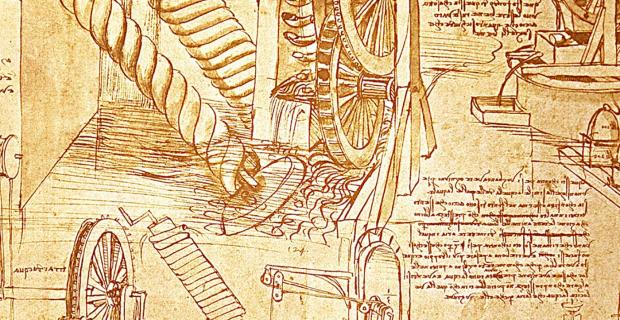

Because the study of patterns requires visualizing and mapping, every time that the study of pattern has been in the forefront, artists have contributed significantly to the advancement of science. In Western science the two most famous examples are Leonardo da Vinci, whose whole scientific work during the Renaissance could be seen as a study of patterns, and the eighteenth-century German poet Goethe, who made significant contributions to biology through his study of patterns.

This opens the door for educators’ integrating the arts into the curriculum. Whether we talk about literature and poetry, the visual arts, music, or the performing arts, there’s hardly anything more effective than art for developing and refining a child’s natural ability to recognize and express patterns.

Because all living systems share sets of common properties and principles of organization, systems thinking can be applied to integrate heretofore fragmented academic disciplines. Biologists, psychologists, economists, anthropologists, and other specialists all deal with living systems. Because they share a set of common principles, these disciplines can share a common framework.

We can also apply the shifts to human communities, where these principles could be called principles of community. Of course there are many differences between ecosystems and human communities. Not everything we need to teach can be learned from ecosystems. Ecosystems do not manifest the level of human consciousness and culture that emerged with language among primates and then came to flourish in evolution with the human species.

Sustainability in the Language of Nature

By applying systems thinking to the multiple relationships interlinking the members of the earth household, we can identify core concepts that describe the patterns and processes by which nature sustains life. These concepts, the starting point for designing sustainable communities, may be called principles of ecology, principles of sustainability, principles of community, or even the basic facts of life. We need curricula that teach our children these fundamental facts of life.

These closely related concepts are different aspects of a single fundamental pattern of organization: nature sustains life by creating and nurturing communities. Among the most important of these concepts, recognized from observing hundreds of ecosystems, are “networks,” “nested systems,” “interdependence,” “diversity,” “cycles,” “flows,” “development,” and “dynamic balance.”

Because members of an ecological community derive their essential properties, and in fact their very existence, from their relationships, sustainability is not an individual property, but a property of an entire network.

At the Center for Ecoliteracy, we understand that solving problems in an enduring way requires bringing the people addressing parts of the problem together in networks of support and conversation. Our watershed restoration work, for example (see “‘It Changed Everything We Thought We Could Do’” in Part III), began with one class of fourth-graders concerned about an endangered species of shrimp, but the work continues today because it evolved into a network that includes students, teachers, parents, funders, ranchers, design and construction professionals, NGOs, and government bodies. Each part of the network makes its own contribution to the project, the efforts of each are enhanced by the work of all, and the network has the resilience to keep the project alive even when individual members leave or move on.

Nested Systems

At all scales of nature, we find living systems nesting within other living systems—networks within networks. Although the same basic principles of organization operate at each scale, the different systems represent levels of differing complexity.

Students working on the Shrimp Project, for example, discovered that the shrimp inhabit pools that are part of a creek within a larger watershed. The creek flows into an estuary that is part of a national marine sanctuary, which is included in a larger bioregion. Events at one level of the system affect the sustainability of the systems embedded in the other levels.

Within social systems such as schools, the individual child’s learning experiences are shaped by what happens in the classroom, which is nested within the school, which is embedded in the school district and then in the surrounding school systems, ecosystems, and political systems. At each level phenomena exhibit properties that do not exist at lower levels. Choosing strategies to affect those systems requires simultaneously addressing the multiple levels and recognizing which strategies are appropriate for different levels. For instance (see “Sustainability—A New Item on the Lunch Menu” in Part IV), the Center recognized that changing schools’ food systems required moving from working with individual schools to working at the district level and then to the larger educational and economic systems in which districts are nested.

Interdependence

The sustainability of individual populations and the sustainability of the entire ecosystem are interdependent. No individual organism can exist in isolation. Animals depend on the photosynthesis of plants for their energy needs; plants depend on the carbon dioxide produced by animals and on the nitrogen fixed by bacteria at their roots. Together, plants, animals, and microorganisms regulate the entire biosphere and maintain the conditions conducive to life.

Sustainability always involves a whole community. This is the profound lesson we need to learn from nature. The exchanges of energy and resources in an ecosystem are sustained by pervasive cooperation. Life did not take over the planet by combat but by cooperation, partnership, and networking. The Center for Ecoliteracy has supported schools such as Mary E. Silveira (see “Leadership and the Learning Community” in Part III) that recognize and celebrate interdependence.

The role of diversity is closely connected with systems’ network structures. A diverse ecosystem will be resilient because it contains many species with overlapping ecological functions that can partially replace one another. When a particular species is destroyed by a severe disturbance so that a link in the network is broken, a diverse community will be able to survive and reorganize itself because other links can at least partially fulfill the function of the destroyed species. The more complex the network’s patterns of interconnections are, the more resilient it will be.

On the other hand, in communities lacking diversity, such as monocrop agriculture devoted to a single species of corn or wheat, a pest to which that species is vulnerable can threaten the entire ecosystem.

In human communities ethnic and cultural diversity may play the same role as does biodiversity in an ecosystem. Diversity means many different relationships, many different approaches to the same problem. At the Center for Ecoliteracy, we have discovered that there is no “one-size-fits-all” sustainability curriculum. We encourage and support multiple approaches to any issue, with different people in different places adapting the teaching of principles of ecology to differing and changing situations.

Matter cycles continually through the web of life. Water, the oxygen in the air, and all the nutrients are continually recycled. Communities of organisms have evolved over billions of years, using and recycling the same molecules of minerals, water, and air. Mutual dependence is much more existential in ecosystems than in social systems because the members of an ecosystem actually eat one another. Ecologists recognized this from the very beginning of ecology. They focused on feeding relations and discovered the concept of the food chain that we still use today. But then they realized that those are not linear chains but cycles, because the bigger organisms are eaten eventually by the decomposer organisms, the insects and bacteria, and so matter cycles through an ecosystem. An ecosystem generates no waste. One species’ waste becomes another species’ food. As I noted in the preface, one reason for the Center’s enthusiasm for school gardens is the opportunity that gardens afford for even very young children to experience nature’s cycles.

The lesson for human communities is obvious. A conflict between economics and ecology arises because nature is cyclical, while industrial processes are linear. Businesses transform resources into products plus waste, and sell the products to consumers, who discard more waste after consuming the products. The ecological principle “waste equals food” means that— if an industrial system is to be sustainable—all manufactured products and materials, as well as the wastes generated in the manufacturing processes, must eventually provide nourishment for something new. In such a sustainable industrial system, the total outflow of each organization—its products and wastes—would be perceived and treated as resources cycling through the system.

All living systems, from organisms through ecosystems, are open systems. Solar energy, transformed into chemical energy by the photosynthesis of green plants, drives most ecological cycles, but energy itself does not cycle. As it is converted from one form of energy to another (for instance, as the chemical energy stored in petroleum is converted into mechanical energy to drive the pistons of an automobile), some of it—often much of it—inevitably flows out and is dispersed as heat. We are therefore dependent on a constant inflow of energy.

A sustainable society would use only as much energy as it could capture from the sun—by reducing its energy demands, using energy more efficiently, and capturing the flow of solar energy more effectively through solar heating, photovoltaic electricity, wind, hydropower, biomass, and other forms of energy that are renewable, efficient, and environmentally benign. Among the complex reasons that the Center for Ecoliteracy promotes farm-to-school food programs (see “Rethinking School Lunch” in Part IV) is that buying food grown close by reduces the unrenewable energy that is required to ship tons of food over thousands of miles to supply school lunches.

Development

All living systems develop, and all development invokes learning. During its development, an ecosystem passes through a series of successive stages, from a rapidly growing, changing, and expanding pioneer community to slower ecological cycles and a more stable fully exploited ecosystem. Each stage in this ecological succession represents a distinctive community in its own right.

At the species level, development and learning are manifested as the creative unfolding of life through evolution. In an ecosystem, evolution is not limited to the gradual adaptation of organisms to their environment, because the environment is itself a network of living organisms capable of adaptation and creativity.

Individuals and environment adapt to one another—they coevolve in an ongoing dance. Because development and coevolution are nonlinear, we can never fully predict or control how the processes that we start will turn out. Small changes can have profound effects. For instance, growing their own food in a school garden can open students to the delight of tasting fresh healthy food, which can create an opportunity to change school menus, which can create a systemwide market for fresh food, which can help sustain local family farms.

On the other hand, nonlinear processes can lead to unanticipated disasters, as occurred with DDT and the development of “superorganisms” resistant to antibiotics, and as some scientists fear could happen with genetic modification of organisms. A sustainable society will exercise caution about committing itself to practices with unknown outcomes. In “The Slow School” (in Part I), Maurice Holt describes the unforeseen consequences of schools’ wholesale commitment to standards-measurement techniques derived from manufacturing and industry.

Dynamic Balance

All ecological cycles act as feedback loops, so that the ecological community continually regulates and organizes itself. When one link in an ecological cycle is disturbed, the entire cycle brings the situation back into balance, and since environmental changes and disturbances happen all the time, ecological cycles continually fluctuate.

These ecological fluctuations take place between tolerance limits, so there is always the danger that the whole system will collapse when a fluctuation goes beyond those limits and the system can no longer compensate for it. The same is true of human communities. Lack of flexibility manifests itself as stress. Temporary stress is essential to life, but prolonged stress is harmful and destructive to the system. These considerations lead to the important realization that managing a social system—a company, a city, or an economy—means finding the optimal values for the system’s variables. Trying to maximize any single variable instead of optimizing it will invariably lead to the destruction of the system as a whole.

Every living system also occasionally encounters points of instability (in human terms, points of crisis or of confusion), out of which new structures, forms, and patterns spontaneously emerge. This spontaneous emergence of order is one of life’s hallmarks and is where we see that creativity is inherent in life at all levels.

One of the most valuable skills for utilizing ecological understanding is the ability to recognize when the time is right for the emergence of new forms and patterns. For example, out of frustration with the failure of piecemeal hunger intervention to have much long-term impact, “community food security” programs are emerging across the country. This movement addresses the overall systems—from energy and transportation to government commodities purchasing to the effect of media on children’s food preferences—that permit communities to meet (or prevent them from meeting) their needs for nutritious, safe, acceptable food.

It is no exaggeration to say that the survival of humanity will depend on our ability in the coming decades to understand these principles of ecology and to live accordingly. Nature demonstrates that sustainable systems are possible. The best of modern science is teaching us to recognize the processes by which these systems maintain themselves. It is up to us to learn to apply these principles and to create systems of education through which coming generations can learn the principles and learn to design societies that honor and complement them.

Excerpted from Ecological Literacy by Fritjof Capra, David Orr, Michael Stone and Zenobia Barlow.

Learn more from Fritjof Capra here. Explore more Bioneers content on environmental education here.

- What Can I Do About the Climate Emergency?

- The Complex Landscape of Education in 2023

- The World Is Drowning in Plastic. Here’s How It All Started

Keep Your Finger on the Pulse

Our bi-weekly newsletter provides insights into the people, projects, and organizations creating lasting change in the world.

- Privacy Overview

- 3rd Party Cookies

- Bioneers Privacy Policy

This website uses cookies so that we can provide you with the best user experience possible. Cookie information is stored in your browser and performs functions such as recognizing you when you return to our website and helping our team to understand which sections of the website you find most interesting and useful.

This website uses Google Analytics and Meta (Facebook) Pixel to collect anonymous information such as the number of visitors to the site, and the most popular pages.

Keeping this cookie enabled helps us to improve our website.

Please enable Strictly Necessary Cookies first so that we can save your preferences!

More information about our Privacy Policy can be found here.

Greater Good Science Center • Magazine • In Action • In Education

Education Articles & More

Five ways to develop “ecoliteracy”, daniel goleman , lisa bennett , and zenobia barlow explain how we can teach kids to care deeply about the environment..

The following is adapted from Ecoliterate: How Educators Are Cultivating Emotional, Social, and Ecological Intelligence . Ecoliterate shows how educators can extend the principles of social and emotional intelligence to include knowledge of and empathy for all living systems.

For students in a first-grade class at Park Day School in Oakland, California, the most in-depth project of their young academic careers involved several months spent transforming their classroom into an ocean habitat, ripe with coral, jellyfish, leopard sharks, octopi, and deep-sea divers (or, at least, paper facsimiles of them). Their work culminated in one special night when, suited with goggles and homemade air tanks, the boys and girls shared what they had learned with their parents. It was such a successful end to their project that several children had to be gently dragged away as bedtime approached.

By the next morning, however, something unexpected had occurred: When the students arrived at their classroom at 8:55 a.m., they found yellow caution tape blocking the entrance. Looking inside, they saw the shades drawn, the lights out, and some kind of black substance covering the birds and otters. Meeting them outside the door, their teacher, Joan Wright-Albertini, explained: “There’s been an oil spill.”

“Oh, it’s just plastic bags,” challenged a few kids, who realized that the “oil” was actually stretched-out black lawn bags. But most of the students were transfixed for several long minutes. Then, deciding that they were unsure if it was safe to enter, they went into another classroom, where Wright-Albertini read from a picture book about oil spills.

The children already knew a little bit about oil spills because of the 2010 accident in the Gulf of Mexico—but having one impact “their ocean” made it suddenly personal. They leaned forward, a few with mouths open, listening to every word. When she finished, several students asked how they could clean up their habitat. Wright-Albertini, who had anticipated the question, showed them footage of an actual cleanup—and, suddenly, they were propelled into action. Wearing gardening gloves, at one boy’s suggestion, they worked to clean up the habitat they had worked so hard to create.

Later, they joined their teacher in a circle to discuss what they learned: why it was important to take care of nature, what they could do to help, and how the experience made them feel. “It broke my heart in two,” said one girl. Wright-Albertini felt the same way. “I could have cried,” she said later. “But it was so rich a life lesson, so deeply felt.” Indeed, through the mock disaster, Wright-Albertini said she saw her students progress from loving the ocean creatures they had created to loving the ocean itself. She also observed them understand a little bit about their connection to nature and gain the knowledge that, even as six and seven year olds, they could make a difference.

It was a tender, and exquisitely planned, teachable moment that reflected what a growing number of educators have begun to identify as a deeply felt imperative: To foster learning that genuinely prepares young people for the ecological challenges presented by this entirely unprecedented time in human history.

“Ecoliterate” is our shorthand for the end goal of this kind of learning, and raising ecoliterate students requires a process that we call “socially and emotionally engaged ecoliteracy”—a process that, we believe, offers an antidote to the fear, anger, and hopelessness that can result from inaction. As we saw in Wright-Albertini’s classroom, the very act of engaging in some of today’s great ecological challenges—on whatever scale is possible or appropriate—develops strength, hope, and resiliency in young people.

Ecoliteracy is founded on a new integration of emotional, social, and ecological intelligence—forms of intelligence popularized by Daniel Goleman . While social and emotional intelligence extend students’ abilities to see from another’s perspective, empathize, and show concern, ecological intelligence applies these capacities to an understanding of natural systems and melds cognitive skills with empathy for all of life. By weaving these forms of intelligence together, ecoliteracy builds on the successes—from reduced behavioral problems to increased academic achievement—of the movement in education to foster social and emotional learning. And it cultivates the knowledge, empathy, and action required for practicing sustainable living.

To help educators foster socially and emotionally engaged ecoliteracy, we have identified the following five practices. These are, of course, not the only ways to do so. But we believe that educators who cultivate these practices offer a strong foundation for becoming ecoliterate, helping themselves and their students build healthier relationships with other people and the planet. Each can be nurtured in age-appropriate ways for students, ranging from pre-kindergarten through adulthood, and help promote the cognitive and affective abilities central to the integration of emotional, social, and ecological intelligence.

1. Develop empathy for all forms of life

At a basic level, all organisms—including humans—need food, water, space, and conditions that support dynamic equilibrium to survive. By recognizing the common needs we share with all organisms, we can begin to shift our perspective from a view of humans as separate and superior to a more authentic view of humans as members of the natural world. From that perspective, we can expand our circles of empathy to consider the quality of life of other life forms, feel genuine concern about their well-being, and act on that concern.

Most young children exhibit care and compassion toward other living beings. This is one of several indicators that human brains are wired to feel empathy and concern for other living things. Teachers can nurture this capacity to care by creating class lessons that emphasize the important roles that plants and animals play in sustaining the web of life. Empathy also can be developed through direct contact with other living things, such as by keeping live plants and animals in the classroom; taking field trips to nature areas, zoos, botanical gardens, and animal rescue centers; and involving students in field projects such as habitat restoration.

Another way teachers can help develop empathy for other forms of life is by studying indigenous cultures. From early Australian Aboriginal culture to the Gwich’in First Nation in the Arctic Circle, traditional societies have viewed themselves as intimately connected to plants, animals, the land, and the cycles of life. This worldview of interdependence guides daily living and has helped these societies survive, frequently in delicate ecosystems, for thousands of years. By focusing on their relationship with their surroundings, students learn how a society lives when it values other forms of life.

2. Embrace sustainability as a community practice

Organisms do not survive in isolation. Instead, the web of relationships within any living community determines its collective ability to survive and thrive.

By learning about the wondrous ways that plants, animals, and other living things are interdependent, students are inspired to consider the role of interconnectedness within their communities and see the value in strengthening those relationships by thinking and acting cooperatively.

The notion of sustainability as a community practice, however, embodies some characteristics that fall outside most schools’ definitions of themselves as a “com- munity,” yet these elements are essential to building ecoliteracy. For example, by examining how their community provisions itself—from school food to energy use—students can contemplate whether their everyday practices value the common good.

Other students might follow the approach taken by a group of high school students in New Orleans known as the “Rethinkers,” who gathered data about the sources of their energy and the amount they used and then surveyed their peers by asking, “How might we change the way we use energy so that we are more resilient and reduce the negative impacts on people, other living beings, and the planet?” As the Rethinkers have shown, these projects can give students the opportunity to start building a community that values diverse perspectives, the common good, a strong network of relationships, and resiliency.

3. Make the invisible visible

Historically—and for some cultures still in existence today—the path between a decision and its consequences was short and visible. If a homesteading family cleared their land of trees, for example, they might soon experience flooding, soil erosion, a lack of shade, and a huge decrease in biodiversity.

But the global economy has created blinders that shield many of us from experiencing the far-reaching implications of our actions. As we have increased our use of fossil fuels, for instance, it has been difficult (and remains difficult for many people) to believe that we are disrupting something on the magnitude of the Earth’s climate. Although some places on the planet are beginning to see evidence of climate change, most of us experience no changes. We may notice unusual weather, but daily weather is not the same as climate disruption over time.

If we strive to develop ways of living that are more life-affirming, we must find ways to make visible the things that seem invisible.

Educators can help through a number of strategies. They can use phenomenal web-based tools, such as Google Earth, to enable students to “travel” virtually and view the landscape in other regions and countries. They can also introduce students to technological applications such as GoodGuide and Fooducate, which cull from a great deal of research and “package” it in easy-to-understand formats that reveal the impact of certain household products on our health, the environment, and social justice. Through social networking websites, students can also communicate directly with citizens of distant areas and learn firsthand what the others are experiencing that is invisible to most students. Finally, in some cases, teachers can organize field trips to directly observe places that have been quietly devastated as part of the system that provides most of us with energy.

4. Anticipate unintended consequences

Many of the environmental crises that we face today are the unintended consequences of human behavior. For example, we have experienced many unintended but grave consequences of developing the technological ability to access, produce, and use fossil fuels. These new technological capacities have been largely viewed as progress for our society. Only recently has the public become aware of the downsides of our dependency on fossil fuels, such as pollution, suburban sprawl, international conflicts, and climate change.

Teachers can teach students a couple of noteworthy strategies for anticipating unintended consequences. One strategy—the precautionary principle—can be boiled down to this basic message: When an activity threatens to have a damaging impact on the environment or human health, precautionary actions should be taken regardless of whether a cause-and-effect relationship has been scientifically confirmed. Historically, to impose restrictions on new products, technologies, or practices, the people concerned about possible negative impacts were expected to prove scientifically that harm would result from them. By contrast, the precautionary principle (which is now in effect in many countries and in some places in the United States) places the burden of proof on the producers to demonstrate harmlessness and accept responsibility should harm occur.

Another strategy is to shift from analyzing a problem by reducing it to its isolated components, to adopting a systems thinking perspective that examines the connections and relationships among the various components of the problem. Students who can apply systems thinking are usually better at predicting possible consequences of a seemingly small change to one part of the system that can potentially affect the entire system. One easy method for looking at a problem systemically is by mapping it and all of its components and interconnections. It is then easier to grasp the complexity of our decisions and foresee possible implications.

Finally, no matter how adept we are at applying the precautionary principle and systems thinking, we will still encounter unanticipated consequences of our actions. Building resiliency—for example, by moving away from mono-crop agriculture or by creating local, less centralized food systems or energy networks—is another important strategy for survival in these circumstances. We can turn to nature and find that the capacity of natural communities to rebound from unintended consequences is vital to survival.

5. Understand how nature sustains life

Ecoliterate people recognize that nature has sustained life for eons; as a result, they have turned to nature as their teacher and learned several crucial tenets. Three of those tenets are particularly imperative to ecoliterate living.

First of all, ecoliterate people have learned from nature that all living organisms are members of a complex, interconnected web of life and that those members inhabiting a particular place depend upon their interconnectedness for survival. Teachers can foster an understanding of the diverse web of relationships within a location by having students study that location as a system.

Second, ecoliterate people tend to be more aware that systems exist on various levels of scale. In nature, organisms are members of systems nested within other systems, from the micro-level to the macro-level. Each level supports the others to sustain life. When students begin to understand the intricate interplay of relation- ships that sustain an ecosystem, they can better appreciate the implications for survival that even a small disturbance may have, or the importance of strengthening relationships that help a system respond to disturbances.

Finally, ecoliterate people collectively practice a way of life that fulfills the needs of the present generation while simultaneously supporting nature’s inherent ability to sustain life into the future. They have learned from nature that members of a healthy ecosystem do not abuse the resources they need in order to survive. They have also learned from nature to take only what they need and to adjust their behavior in times of boom or bust. This requires that students learn to take a long view when making decisions about how to live.

These five practices, developed by the Berkeley-based Center for Ecoliteracy , offer guideposts to exciting, meaningful, and deeply relevant education that builds on social and emotional learning skills. They can also plant the seeds for a positive relationship with the natural world that can sustain a young person’s interest and involvement for a lifetime.

About the Authors

Daniel Goleman

Daniel Goleman, Ph.D., is the author of the bestsellers Emotional Intelligence , Social Intelligence , and Focus: The Hidden Driver of Excellence . He has been awarded the American Psychological Association’s Lifetime Achievement Award and is a Fellow of the American Association for the Advancement of Science. You can learn more about Goleman and his work at www.danielgoleman.info .

Zenobia Barlow

Lisa bennett.

Lisa Bennett is a Bay Area writer focused on solutions to climate change. She is the coauthor of Ecoliterate: How Educators Are Cultivating Emotional, Social, and Ecological Intelligence . Follow her on Twitter @LisaPBennett

You May Also Enjoy

This article — and everything on this site — is funded by readers like you.

Become a subscribing member today. Help us continue to bring “the science of a meaningful life” to you and to millions around the globe.

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Springer Nature - PMC COVID-19 Collection

Assessing ecological literacy and its application based on linguistic ecology: a case study of Guiyang City, China

Changchen ha.

1 School of Foreign Studies, South China Agricultural University, No. 483 Wushan Road, Guangzhou, 510640 Guangdong China

Guowen Huang

2 Center for Ecolinguistics, South China Agricultural University, No. 483 Wushan Road, Guangzhou, 510640 Guangdong China

Jiaen Zhang

3 College of Natural Resources and Environment, South China Agricultural University, No. 483 Wushan Road, Guangzhou, 510640 Guangdong China

4 Guangdong Provincial Key Laboratory of Eco-Circular Agriculture, No. 483 Wushan Road, Guangzhou, 510640 Guangdong China

Shumin Dong

5 School of Chinese Ethnic Minority Languages and Literature, Minzu University of China, No. 27 Zhongguancun South Avenue, Beijing, 100081 China

Associated Data

The datasets and materials used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding authors on reasonable request.

To address the frequent emergence of ecological problems, ecology has intersected with various disciplines. From the perspective of linguistic ecology, ecological literacy is an important concept that combines the subjects of ecology and linguistics. It not only discusses ecological issues, but also establishes a linguistic framework. Here, we constructed a quantitative method of assessing ecological literacy from the perspective of linguistic ecology. Ecological literacy was divided into five parts: ecological knowledge literacy, ecological awareness literacy, ecological ethics literacy, ecological emotional literacy, and ecological behavioral literacy. Each of these was set with four quantitative indicators that were evaluated through eight questions. A case study was conducted to investigate the ecological literacy of the inhabitants of Guiyang City, one of China’s top ten ecologically advanced cities. The results showed that the proposed assessment method was an effective way to evaluate the level of ecological literacy comprehensively. In the case analysis, the overall ecological literacy level of Guiyang inhabitants was relatively good, and the levels of the five specific dimensions of them in descending order were as follows: ecological ethics literacy, ecological emotional literacy, ecological awareness literacy, ecological knowledge literacy, and ecological behavioral literacy. The results of this study are conducive to the production of targeted ways to improve the level of ecological literacy for sustainable development.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s11356-021-16753-7.

Introduction

Since the 1900s, with the accelerated development of the economy, science, and technology, human life has greatly improved. Meanwhile, it has also brought about many global ecological problems pertaining to population, resources, and the environment. In particular, the outbreak of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), which began at the end of 2019, has once again sounded the alarm regarding human attitudes and behavior toward nature. In the context of the tense relationship between humans and the natural environment, researchers in many countries and different fields have started looking at the surrounding world from an ecological perspective, re-examining the thoughts and behavior of humankind, and working hard to solve environmental problems. Thus, the phenomenon of so-called ecologicalization in contemporary science has formed many emerging interdisciplinary subjects related to ecology (Li and Yuan 1988 ), including environmental ecology (Jin 1992 ), human ecology (Wang 1998 ), urban ecology (Wu et al. 2014 ), and linguistic ecology (Alexander and Stibbe 2014 ; Huang 2016 ). The key point is to study many problems in human production and life from the perspective of ecology or by using the principles of ecology.

It is crucial to our survival and development to establish integrity in the relationship between humans and nature. Therefore, we must understand life-sustaining ecosystems and their operating methods, while gaining ecological knowledge. This is the basis for ecological literacy, which plays an important role in the sustainable development of society. With the emergence of multiple negative factors, such as industrialization, urbanization, population growth, resource consumption, and the endangerment and extinction of species, the current epoch has been named the Anthropocene (Crutzen and Stoermer 2000 ; Steffen et al. 2007 ; Scholz 2011 ; Huang and Xiao 2017 ), signaling a series of changes to the relationship between humans and nature. People are generally worried that the overall level of ecological literacy in many countries and regions is insufficient to make effective decisions for an ecologically sustainable lifestyle. Although ecological knowledge and ecological literacy are only contributing factors to sustainable development, they are fundamental and cannot be replaced by other factors. This has prompted various countries and regions to assess the level of ecological literacy and promote research in this area.

Ecological literacy involves many factors, making its assessment especially complicated. In recent years, many researchers have developed ecological literacy assessment tools and applied them to research on middle school and secondary education (NAAEE 2011a , 2011b ; Shen et al. 2020 ). At the same time, some researchers have focused on the ecological literacy of adults (Arcury 1990 ; McDaniel and Alley 2005 ; Davidson 2010 ; Pitman and Daniels 2016 ; Pitman et al. 2016 , 2017 ). Other studies on ecological literacy have covered a more comprehensive age range, by including both adolescents and adults (Wang et al. 2017 ; Lin and Cai 2019 ). But because such studies cover a wider range of ages, the scope of other factors, such as regional selection, is usually relatively small.

In China, research on ecological literacy and the related characteristics of inhabitants in ecologically advanced cities is important because it is conducive to the generation and optimization of sustainable decisions. Here, we concentrated on ecological literacy in Guiyang City, China. We proposed an assessment method based on linguistic ecology. We applied the proposed method to a case study of the inhabitants in Guiyang. We asked three questions: (1) What does the term “ecological literacy” mean in the perspective of linguistic ecology? (2) How can ecological literacy be assessed in an efficient and meaningful way in China? (3) What can we learn from the case study of Guiyang City about the inhabitants’ ecological literacy level? These research questions are answered in the next two sections.

Concepts and methods

Linguistic ecology.

In the expansion of ecology to the humanities, the combination of ecology and linguistics has formed an emerging discipline, called linguistic ecology or the ecology of language. From the perspective of ecology, the roots of linguistic ecology can be traced back to research on human ecology. Human ecology advocates the use of ecological methods to explore the relationship between humans and nature. Rusong Wang ( 1998 ), a well-known ecologist in China, described human ecology as the combination of ecology, sociology, economics, and other disciplines at different levels. Although these disciplines have different origins, they all involve the subject of the relationship between humans and nature, and they require the application of systematic, comprehensive, and evolutionary ecological methods.

Linguistic ecology emphasizes the influence of language on the sustainable relationship of life, including the relationships between language and humans, humans and other species, and humans and the physical environment. Linguistic ecology aims to reveal the interaction between language and the environment, mainly through the study of the ecological factors of language and the relationship between language and the ecological environment (Alexander and Stibbe 2014 ; Huang 2016 ), with the ultimate aim of enhancing ecological awareness and ecological literacy. This means that ecological philosophy is an important guiding factor. Linguistic ecology also refers to the problem of ecological thought. Such practices can serve as a guide to achieve agreement between knowledge and action, solving the ecological problems, and changing the ecological status quo.

Ecological literacy

Literacy and environmental literacy.

The term “literacy” first appeared in the late nineteenth century. It was originally exclusive to the fields of reading and writing and referred to the ability to read and write (Stibbe 2009 ). It was thus terminology that first pertained to linguistics. Since the Industrial Revolution, usage of the term “literacy” has gradually expanded. In the 1960s, a literate citizen was thought to have knowledge and capability in a particular field or fields, and to be able to take effective action on many complex issues facing society (McBridge et al. 2013 ). Therefore, the term “literacy” has expanded to include knowledge of specific disciplines or problems, and it can now refer to one’s level of knowledge and capability in such fields. The terms “environmental literacy” and “ecological literacy” have since appeared in ecological research. Ecological literacy evolved from environmental literacy, and these two concepts are inseparable.

The term “environmental literacy” was first used by Charles Roth in research on the topic of understanding environmentally literate citizens (Roth 1968 ; Roth 1992 ; Morrone et al. 2001 ; O’ Brien 2007 ). But attention to the issue began in the early 1960s. Rachel Carson questioned the abnormal phenomena of the natural environment in America in her book, "Silent Spring" (Carson 1962 ). At present, the most widely used definition of environmental literacy is the one proposed by the NAAEE, which indicated that environmental literacy includes awareness and concern about the environment and environmental issues, as well as knowledge, skills, and the motivation to solve current related problems and prevent new problems (NAAEE 2000/2004 , 2011a , 2011b ; Scholz 2011 ). Although this research does not discuss the content and framework of environmental literacy directly, environmental literacy is a broader concept. Ecological literacy is a secondary concept, and it is also the development of the connotation of environmental literacy. Ecological literacy provides the necessary ecological foundation for environmental literacy.

Concepts and framework of ecological literacy in linguistic ecology

Ecological literacy is a relatively abstract concept, and scholars differ in understanding the concept and framework of ecological literacy. After Paul Risser pointed out in 1986 that America had certain shortcomings in scientific literacy, especially ecology-based literacy, many researchers began discussing the concept of ecological literacy (Risser 1986 ; Orr 1992 ; Berkowitz et al. 2005 ; Coyle 2005 ; Bruyere 2008 ; McBride et al. 2013 ; Pitman and Daniels 2016 ; Huang and Zhao 2019 ; Huang and Ha 2021 ). Coyle ( 2005 ) proposed a visual pyramid to discuss personal ecological literacy. The pyramid is composed of three levels from bottom to top: environmental knowledge, environmental attitudes, and ecological literacy. Ecological literacy is at the top of the pyramid because it is developed through personal environmental knowledge, values, and actions taken in response to environmental problems. Other researchers have divided ecological literacy into different categories: ecological knowledge, ecological attitudes, and ecological behavior (Bruyere 2008 ); or ecological knowledge literacy, ecological ethics literacy, ecological emotional literacy, and ecological behavioral literacy (Huang and Zhao 2019 ).

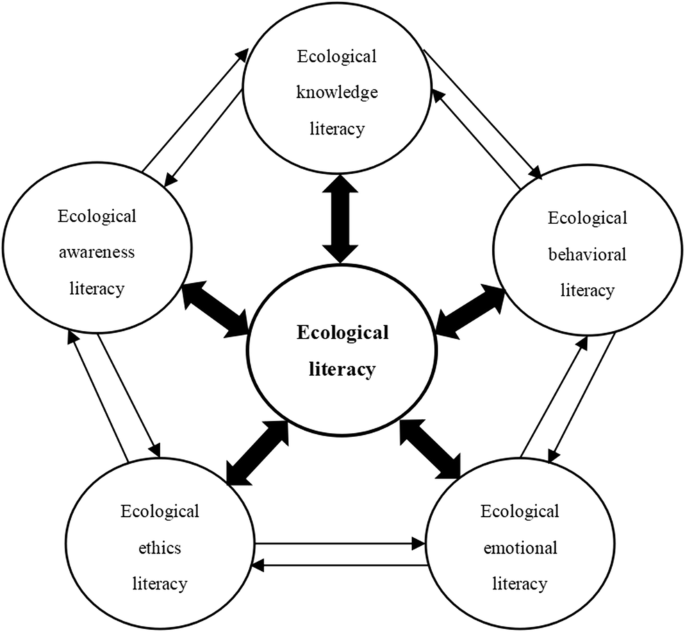

We submit that ecological awareness is another important part of the framework of ecological literacy in linguistic ecology. Thus, we propose the following five factors: (1) ecological knowledge literacy; (2) ecological awareness literacy; (3) ecological ethics literacy; (4) ecological emotional literacy; and (5) ecological behavioral literacy. In essence, ecological literacy refers to the acquisition and dissemination of ecological knowledge, enhancing awareness of ecological protection, and ultimately guiding the sustainable development of ecological behavior to achieve a higher level of ecological literacy. In other words, the five dimensions of ecological literacy comprise a unified whole, and each of them is almost equally important theoretically (Figure (Figure1). 1 ). They influence each other interactively. Of these, ecological knowledge literacy is foundational, ecological awareness literacy indicates the direction of action, ecological ethics literacy emphasizes moral standards, ecological emotional literacy is the internal driving force, and ecological behavioral literacy is the ultimate goal.

Formation process of ecological literacy

People acquire ecological knowledge through various channels such as national or local policies, social-level publicity and education, family guidance, and gradually formed ecological knowledge literacy. As ecological problems become more and more serious, ecosystems continue to be destroyed, and natural disasters frequently occur, people will have a sense of crisis and indirectly realize the importance of harmonious coexistence between humans and the natural environment. Through their own ecological knowledge, they will enhance their awareness and emotions regarding environmental protection. With strong ecological awareness, people will also be restricted by ecological ethics and morals, and their ecological awareness literacy will be regulated. Moreover, people affected by ecological ethics will continue to judge their own psychological direction based on their own emotional attitudes or ecological philosophy. Positive emotional factors will form a certain ability for ecological emotional literacy, which will provide a strong motivation for ecological behavior. Under the comprehensive effects of various national and regional regulations, as well as their own ecological knowledge, ecological awareness, ecological ethics, and ecological emotional literacy, people will carry out their own ecological protection behavior and form their own ecological behavioral literacy. Ecological literacy levels will thus be improved. After ecological literacy levels improve, further self-reflection is needed to continue to strengthen the acquisition of ecological knowledge, the enhancement of ecological awareness, the consolidation of ecological ethics, and the improvement of ecological emotion and ecological behavior. This will be more conducive to the development of ecological society, and it will produce a higher level of ecological literacy to realize the effect of ecological literacy on ecological knowledge literacy.

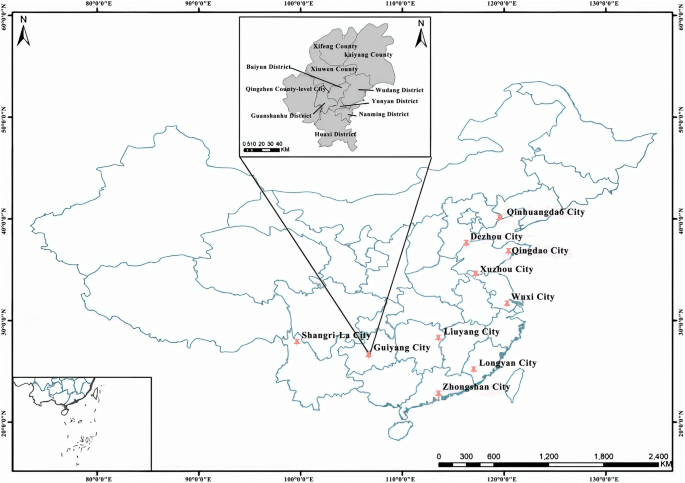

In July 2015, the first National Ecological Civilization Construction Summit Forum and the City and Scenic Area Ecological Civilization Achievement Conference was held in Beijing, China. The theme of the meeting was “Promoting the Construction of Ecological Civilization and Building a Beautiful Green Home”. The following cities in China were named the most ecologically advanced (i.e., “ecologically civilized”): Longyan City, Zhongshan City, Guiyang City, Qinhuangdao City, Liuyang City, Wuxi City, Xuzhou City, Dezhou City, Qingdao City, Shangri-La City (Figure (Figure2 2 ).

Distribution of China’s top ten ecologically advanced cities and administrative district division of Guiyang City

Combining the actual situation of the surveyed cities and the feasibility of the survey process, we selected Guiyang City as a case study. The participants were local inhabitants, and according to the overall sampling statistics method, an effective sample size of inhabitants was randomly selected for the research.

Guiyang City is the capital of Guizhou Province. It is located in the southwestern region of China and in the center of Guizhou Province, at 106°07′–107°17′ E, 26°11′–26°55′ N (Figure (Figure2). 2 ). It is the political, economic, cultural, scientific, educational, and transportation center of Guizhou Province. The construction of ecological civilization in Guiyang City started early, beginning with the completion of two forest belts around the city in the 1980s. In 2002, it was designated by the State Environmental Protection Administration as the country’s first pilot unit for an ecological city with a circular economy. In 2009, there was an ecological civilization conference held in Guiyang City, and this was upgraded to the Guiyang International Forum on Ecological Civilization in 2013, the only national-level international forum on ecological civilization in China at that time. In 2018, Guiyang City was listed among the “2018 Top Ten Cities for Green Development and Ecological Civilization Construction”.

As of the end of 2018, Guiyang City has a land area of 8043.37 km 2 and a forest coverage rate of 39.19%, including six districts, three counties, and one county-level city (Figure (Figure2). 2 ). The permanent population (i.e., inhabitants for 6 months or longer) is 4,881,900, including an urban population of 3,682,400 and a rural population of 1,199,500, covering more than 30 ethnic minorities. We conducted a sample survey of the inhabitants of Guiyang City, taking six districts, three counties, and one county-level city in Guiyang City as the sampling level, and stratifying the inhabitants of each district (city, county) according to a certain proportion. Random sampling was used to reflect the overall level of the ecological literacy of the inhabitants in Guiyang City. One issue that needs special attention here is the definition of the research object “inhabitants”. In the survey process, combined with the statistics of the permanent population in the "Guiyang Statistical Yearbook 2019", the “inhabitants” involved in this study refer to the permanent inhabitants of Guiyang City, that is, the people who had lived in Guiyang City for 6 months or longer before the start of the survey (i.e., before September 30th, 2020) and who lived in Guiyang City throughout the survey. Other populations were not within the scope of the study.

Questionnaire design

Design steps.

To design the questionnaire, we proceeded as follows. The first step was to determine the conceptual framework and dimensions of “ecological literacy,” including ecological knowledge literacy, ecological awareness literacy, ecological ethics literacy, ecological emotional literacy, and ecological behavioral literacy as the first-level indicators of ecological literacy. An analytic hierarchy process in statistics requires that the indicators considered can be investigated and measured in actual situations; this required us to construct a series of decomposition content reflecting the force and influence of the elements, and to analyze the decomposition content. This content is described in detail (Xiao and Fan 2011 ). Therefore, within the scope of each first-level indicator, after discussions with five Chinese experts and scholars in the field of ecology, especially in the field of linguistic ecology, we formulated second-level indicators under the five first-level indicators of the concept of ecological literacy in this study (Table (Table1). 1 ). The weight of each first-level indicator and second-level indicator was the same, and they were regarded as equally important. It means the number of second-level indicators in each dimension has to be equal. In a similar way, the number of survey questions in each second-level indicator has also to be equal. Taking into account the actual situation of the questionnaire survey, too many or too few survey questions may affect the effectiveness of the survey results. There are four second-level indicators under each first-level indicator finally. For this study, such a number (four second-level indicators with eight questions) not only guarantees the comprehensiveness of the survey contents, but also does not reduce the effectiveness of the participants’ answers due to too many survey questions.

Second-level indicators of ecological literacy

During the second step, we devised specific questions in the questionnaire under each second-level indicator. The topics were selected with reference to the “China Urban Public Environmental Awareness Questionnaire” developed by the Public Environmental Awareness Research Group of the State Environmental Protection Administration and the Public Environmental Awareness Research Group of the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences in 2005, and an effective survey developed by Pitman and Daniels ( 2016 ) of the University of South Australia on ecological literacy level assessment scale and questionnaire questions. At the same time, combined with China’s ecologically advanced cities and current heated issues regarding the environment, as well as the specific situation in Guiyang City, the first draft of the research questionnaire was formed. Although part of the questionnaire design draws on preliminary research results, due to the quantitative assessment of the ecological literacy level, there is currently no unified assessment scale. Therefore, we designed most of the content in this step.

The third step was to revise and improve the first draft of the questionnaire to form the final version of the questionnaire. This step involved two statistical forecast stages. After the second forecast stage, we tested the reliability of the questionnaire within an acceptable range before proceeding to the actual measurement stage. Subsequently, the forecast respondents’ opinions and suggestions on the content of the questionnaire were collected, and the content of the questionnaire was carefully analyzed and improved. Finally, after issuing the questionnaire and collecting responses during the actual measurement phase, we examined the total reliability of the questionnaire in detail, as well as the validity of the scale, to ensure the authentic validity of the survey data for data analysis.

Topic structure

The final version of the questionnaire contained 60 survey questions. Of these, there were 40 questions on ecological literacy. In what follows, we focus on discussing this part. The ecological literacy survey was designed to assess the level of ecological literacy of the inhabitants in Guiyang City, and the scores needed to be measured quantitatively. The measurement part of the ecological literacy level score of this study was designed in the form of a five-point Likert scale (five-point scoring). There were 40 survey questions, and each question had five options ( Appendix ). The options were sorted in ascending or descending order. This could better distinguish the nuances of the respondent’s ecological literacy level and thus produce more accurate measurement results. The minimum score that a respondent could get in this part was 40 points, and the maximum score was 200 points. Specifically, there were five topics: ecological knowledge, ecological awareness, ecological ethics, ecological emotion, and ecological behavior. Each topic included eight sub-topics to examine the corresponding second-level indicators of ecological literacy.

Reliability and validity

The reliability of the questionnaire, that is, whether the results of the questionnaire were internally consistent, was evaluated by Cronbach’s Alpha reliability coefficient. Normally, a Cronbach’s Alpha above 0.70 ( α ≥0.70) indicates that the questionnaire has a certain degree of credibility (Cortina 1993 ; Gleim and Gliem 2003 ), and the higher the value, the more reliable the data results, and the greater the confidence. But if the Cronbach’s Alpha is between 0.60 and 0.70 (0.60≤ α <0.70), the result of reliability is also acceptable to the study (Zhou 2017 : 44). Two reliability tests were carried out in this study. The reliability of 97 samples in the prediction phase was tested, and the Cronbach’s Alpha was 0.872 (overall ecological literacy level). Then, we tested all 494 samples used for the analysis. The Cronbach’s Alpha was 0.888 (overall ecological literacy level), and the reliability coefficients of all five dimensions were also above 0.60. Its internal consistency (the questionnaire) was thus within an acceptable range, indicating high credibility suitable for further statistical analysis of data.

The validity of a questionnaire mainly refers to the degree of validity of the questionnaire measurement results. The higher the validity of the questionnaire, the closer the collected data are to the actual purpose of the survey. Generally, the validity of a questionnaire includes content validity and structural validity (Chai 2010 ). Specifically, the content validity of a questionnaire is combined with expert judgments, and structural validity refers to the construction validity, which mainly detects the structure of a questionnaire by the factors of the Estimate, CR, and AVE. The evaluation criteria for these factors were set as Estimate above 0.45, CR above 0.60, AVE above 0.36 (Wu 2010 , 2013 ; Wan et al. 2015 ). Because the dimensions of our questionnaire are discussed in detail in the previous sections, that is, because the dimensions of the questionnaire are known, the structural validity of the questionnaire was evaluated by confirmatory factor analysis using AMOS 23.0 software, to ensure that the questionnaire had explanatory power. After testing this, the content validity and structural validity (Estimate: 0.67; CR: 0.95; AVE: 0.49) of our questionnaire were found to be within the acceptable range.

Data collection

We adopted a combination of network distribution and paper distribution; network distribution was the main method, and paper distribution was supplementary. Online distribution involved a questionnaire network platform, with the questionnaire sent and received by e-mail; paper distribution involved using centralized fixed-point distribution and mailing. We combined the total permanent population of Guiyang City and the population of each district (city, county) in the survey area and decided to use the 10 districts (cities, counties) of Guiyang City as a benchmark, with random stratification according to a ratio of 1:10,000 sampling.

Therefore, at least 494 copies of the questionnaire needed to be distributed during the survey process of this study. The survey of participants was completely based on the principle of voluntary participation, and the survey results were anonymous. However, a minimum of 494 questionnaires were needed to guarantee the validity. In order to ensure that the minimum effective sample size drawn met the needs of the survey, we increased the number of questionnaire surveys by 10% on the basis of the minimum sample size. Thus, we needed to distribute at least 494 × (1 + 10%) = 543.4 (take 544) questionnaires. Hopkins et al. ( 1990 ) pointed out in related research that subjects who fill out questionnaires faster do not necessarily answer interview questions better, and the evaluation process should not consider speed. Thus, the speed of answering has a negligible relationship with the understanding of knowledge. Therefore, we did not have strict requirements on the answering speed of the questionnaire, although it usually took about 10–15 min to complete. The duration of the entire survey was about 6 weeks in October and November of 2020.

In this study, a total of 600 questionnaires were distributed and 591 were collected, of which 539 were valid questionnaires. Then, in accordance with the above-mentioned standard of 494 samples and the number of samples drawn in each administrative region, questionnaires that exceeded the sample size were randomly eliminated. Thus, 494 valid questionnaires were summarized, numbered, and entered into a Microsoft Excel table one-by-one.

Data analysis

We analyzed the collected data using SPSS 25.0. To do so, we analyzed the overall ecological literacy level of the inhabitants in Guiyang City. The data from this part were mainly obtained from the score statistics of the 40 questions in the questionnaire, including the normality test of the questionnaire, descriptive statistics of the overall level analysis, and descriptive statistical analysis and correlation analysis of the five dimensions of ecological literacy. Then, we conducted descriptive statistical analysis and a brief analysis of the second-level indicators in the five dimensions of ecological knowledge literacy, ecological awareness literacy, ecological ethics literacy, ecological emotional literacy, and ecological behavioral literacy. This was done to understand the ecological literacy of the inhabitants of Guiyang at a micro-level so that we could propose targeted strategies to improve the level of ecological literacy.

Results and discussion

Overall ecological literacy level.

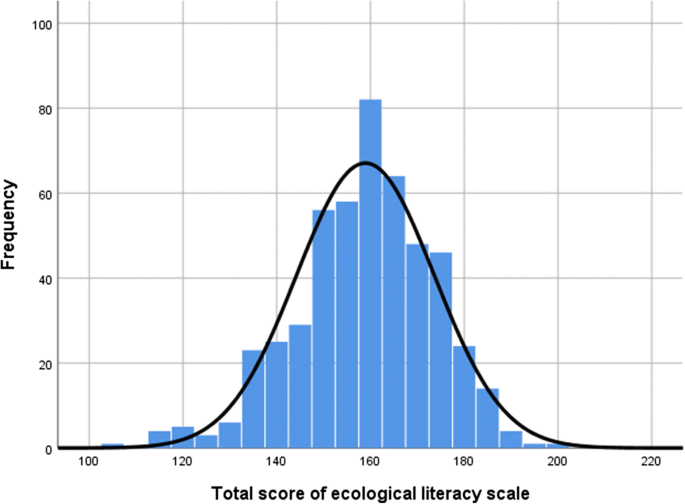

The overall ecological literacy level of the participants is the total score from the 40 questions in the questionnaire. The descriptive statistics of SPSS 25.0 show that the total ecological literacy measurement scores of the 494 Guiyang inhabitants surveyed were normally distributed on the whole. The average score was 158.91 points (158.91 ± 14.693, 79.46%), with a minimum of 105 points, and a maximum of 199 points (Figure (Figure3). 3 ). From the score rate of the scale here, it can be seen that the overall ecological literacy level of the inhabitants of Guiyang City was relatively good. The average score rate of the questionnaire was close to 80%, which was at the middle and upper levels.

Total score histogram of ecological literacy in Guiyang City

In the descriptive statistical analysis of the five first-level indicators of the ecological literacy level of Guiyang inhabitants, we found that there were developments in the internal structure of the five dimensions of ecological knowledge literacy, ecological awareness literacy, ecological ethics literacy, ecological emotional literacy, and ecological behavioral literacy. For the problem of imbalance, there were big differences between different dimensions (Table (Table2), 2 ), but the overall average score rate was higher. Each dimension consisted of eight scale questions. That is, the range of scores that the respondent could obtain was [8, 40] in each dimension.

Descriptive statistical analysis of five dimensions of the ecological literacy levels of Guiyang inhabitants

From Table Table2, 2 , it can be seen that, among the ecological literacy levels of Guiyang inhabitants, the level of ecological ethics literacy was the highest (36.41 ± 4.010), and their average scoring rate reached 91.03%; the level of ecological emotional literacy was slightly lower than that of ecological ethics (35.35 ± 3.758), and ecological awareness literacy was lower (33.21 ± 3.918). The average scores of the interviewees were relatively low in terms of ecological knowledge literacy (29.11 ± 5.191) and ecological behavioral literacy (24.83 ± 4.775), but their average score rates were still higher than 60% (72.78% and 62.08%, respectively). The average score of these two dimensions was significantly lower than that of the other three dimensions, but from a macro point of view, the levels of these two dimensions were still within a good range. This showed that the inhabitants of Guiyang City had a high level of ecological literacy, especially in terms of ecological ethics, ecological emotion, and ecological awareness. However, there is room for improvement in the possessing of ecological knowledge and the ability and level of implementing ecological literacy in specific actions.

Subsequently, we conducted a bi-variate correlation analysis of the relationship among each dimension of ecological literacy (Table (Table3), 3 ), with the purpose of exploring the correlation between each dimension and the other four dimensions. Owing to the uneven levels of all five dimensions of ecological literacy, the correlation analysis between each two dimensions can help to improve a certain specific dimension level, relying on whether they are related, whether the relationship is positive or negative, and the strength of the correlation with other dimensions. Based on a variety of statistical data, the overall situation was coordinated, and solutions were proposed in many aspects.

Correlation analysis of the five dimensions of ecological literacy levels of Guiyang inhabitants

Note: The number of cases is 494

"**" means it is at the 0.01 level (two-tailed) and that the correlation is significant

Table Table3 3 shows that there was no direct correlation between ecological ethics literacy and ecological behavioral literacy ( P = 0.500 > 0.05). There was a significant correlation between the other four dimensions ( P < 0.05), and it was a significant correlation at the 0.01 level. A closer look at the Pearson’s correlation coefficients shows that they were all positive numbers, so that all dimensions with correlation were positive correlations. First, the correlation coefficient between ecological ethics literacy and ecological emotional literacy was the largest ( R = 0.617**, 0.6 < R ≤ 0.8), indicating that there was a significant positive and strong correlation between ecological ethics literacy and ecological emotional literacy. Second, the correlation coefficient between ecological awareness literacy and ecological ethics literacy ( R = 0.597**, 0.4 < R ≤ 0.6), and between ecological awareness literacy and ecological emotional literacy ( R = 0.514**, 0.4 < R ≤ 0.6) was only lower than the correlation coefficient between ecological ethics literacy and ecological emotional literacy. In particular, the correlation coefficient between ecological awareness literacy and ecological ethics literacy was very close to 0.6. Therefore, ecological awareness literacy and ecological ethics literacy had a significant moderate correlation, and ecological awareness literacy and ecological emotional literacy had a significant moderate correlation, too. Third, there was a significant positively weak correlation between each dimension of ecological literacy. The correlation coefficient (0.2 < R ≤ 0.4) from high to low was as follows: ecological emotional literacy and ecological behavioral literacy ( R = 0.365**), ecological knowledge literacy and ecological behavioral literacy ( R = 0.338**), ecological knowledge literacy and ecological emotional literacy ( R = 0.296**), ecological knowledge literacy and ecological awareness literacy ( R = 0.288**), and ecological knowledge literacy and ecological ethics literacy ( R = 0.209**). Finally, there was a significant but very low positive correlation between a group of dimensions (0 ≤ R ≤ 0.2), namely, the correlation coefficient between ecological awareness literacy and ecological behavioral literacy ( R = 0.138**).

During the development of ecologically advanced cities, we should focus on acquiring ecological theory and the practice of ecological actions for the ecological literacy level of the inhabitants of Guiyang City. From the correlation coefficients related to the two dimensions of ecological knowledge literacy and ecological behavioral literacy in Table Table3, 3 , it can be seen that the coefficients related to them in the five dimensions are in the range of weak to very low correlation. This implies that, in the process of improving ecological knowledge literacy and ecological behavioral literacy, while taking other dimensions into account to improve both literacy indirectly, we must consciously focus on themselves. The inhabitants, who have strong ecological awareness and social responsibility, are able to strengthen their ecological knowledge, so that they can improve their ecological knowledge level. Finally, they can transform their strong ecological knowledge and ecological awareness into practice, and practice ecological literacy in their actions. Moreover, they can influence other inhabitants to become more ecologically literate.

Specific analysis of the five dimensions

Ecological knowledge literacy level.