Places on our 2024 summer school are filling fast. Don’t miss out. Enrol now to avoid disappointment

- 40 Useful Words and Phrases for Top-Notch Essays

To be truly brilliant, an essay needs to utilise the right language. You could make a great point, but if it’s not intelligently articulated, you almost needn’t have bothered.

Developing the language skills to build an argument and to write persuasively is crucial if you’re to write outstanding essays every time. In this article, we’re going to equip you with the words and phrases you need to write a top-notch essay, along with examples of how to utilise them.

It’s by no means an exhaustive list, and there will often be other ways of using the words and phrases we describe that we won’t have room to include, but there should be more than enough below to help you make an instant improvement to your essay-writing skills.

If you’re interested in developing your language and persuasive skills, Oxford Royale offers summer courses at its Oxford Summer School , Cambridge Summer School , London Summer School , San Francisco Summer School and Yale Summer School . You can study courses to learn english , prepare for careers in law , medicine , business , engineering and leadership.

General explaining

Let’s start by looking at language for general explanations of complex points.

1. In order to

Usage: “In order to” can be used to introduce an explanation for the purpose of an argument. Example: “In order to understand X, we need first to understand Y.”

2. In other words

Usage: Use “in other words” when you want to express something in a different way (more simply), to make it easier to understand, or to emphasise or expand on a point. Example: “Frogs are amphibians. In other words, they live on the land and in the water.”

3. To put it another way

Usage: This phrase is another way of saying “in other words”, and can be used in particularly complex points, when you feel that an alternative way of wording a problem may help the reader achieve a better understanding of its significance. Example: “Plants rely on photosynthesis. To put it another way, they will die without the sun.”

4. That is to say

Usage: “That is” and “that is to say” can be used to add further detail to your explanation, or to be more precise. Example: “Whales are mammals. That is to say, they must breathe air.”

5. To that end

Usage: Use “to that end” or “to this end” in a similar way to “in order to” or “so”. Example: “Zoologists have long sought to understand how animals communicate with each other. To that end, a new study has been launched that looks at elephant sounds and their possible meanings.”

Adding additional information to support a point

Students often make the mistake of using synonyms of “and” each time they want to add further information in support of a point they’re making, or to build an argument . Here are some cleverer ways of doing this.

6. Moreover

Usage: Employ “moreover” at the start of a sentence to add extra information in support of a point you’re making. Example: “Moreover, the results of a recent piece of research provide compelling evidence in support of…”

7. Furthermore

Usage:This is also generally used at the start of a sentence, to add extra information. Example: “Furthermore, there is evidence to suggest that…”

8. What’s more

Usage: This is used in the same way as “moreover” and “furthermore”. Example: “What’s more, this isn’t the only evidence that supports this hypothesis.”

9. Likewise

Usage: Use “likewise” when you want to talk about something that agrees with what you’ve just mentioned. Example: “Scholar A believes X. Likewise, Scholar B argues compellingly in favour of this point of view.”

10. Similarly

Usage: Use “similarly” in the same way as “likewise”. Example: “Audiences at the time reacted with shock to Beethoven’s new work, because it was very different to what they were used to. Similarly, we have a tendency to react with surprise to the unfamiliar.”

11. Another key thing to remember

Usage: Use the phrase “another key point to remember” or “another key fact to remember” to introduce additional facts without using the word “also”. Example: “As a Romantic, Blake was a proponent of a closer relationship between humans and nature. Another key point to remember is that Blake was writing during the Industrial Revolution, which had a major impact on the world around him.”

12. As well as

Usage: Use “as well as” instead of “also” or “and”. Example: “Scholar A argued that this was due to X, as well as Y.”

13. Not only… but also

Usage: This wording is used to add an extra piece of information, often something that’s in some way more surprising or unexpected than the first piece of information. Example: “Not only did Edmund Hillary have the honour of being the first to reach the summit of Everest, but he was also appointed Knight Commander of the Order of the British Empire.”

14. Coupled with

Usage: Used when considering two or more arguments at a time. Example: “Coupled with the literary evidence, the statistics paint a compelling view of…”

15. Firstly, secondly, thirdly…

Usage: This can be used to structure an argument, presenting facts clearly one after the other. Example: “There are many points in support of this view. Firstly, X. Secondly, Y. And thirdly, Z.

16. Not to mention/to say nothing of

Usage: “Not to mention” and “to say nothing of” can be used to add extra information with a bit of emphasis. Example: “The war caused unprecedented suffering to millions of people, not to mention its impact on the country’s economy.”

Words and phrases for demonstrating contrast

When you’re developing an argument, you will often need to present contrasting or opposing opinions or evidence – “it could show this, but it could also show this”, or “X says this, but Y disagrees”. This section covers words you can use instead of the “but” in these examples, to make your writing sound more intelligent and interesting.

17. However

Usage: Use “however” to introduce a point that disagrees with what you’ve just said. Example: “Scholar A thinks this. However, Scholar B reached a different conclusion.”

18. On the other hand

Usage: Usage of this phrase includes introducing a contrasting interpretation of the same piece of evidence, a different piece of evidence that suggests something else, or an opposing opinion. Example: “The historical evidence appears to suggest a clear-cut situation. On the other hand, the archaeological evidence presents a somewhat less straightforward picture of what happened that day.”

19. Having said that

Usage: Used in a similar manner to “on the other hand” or “but”. Example: “The historians are unanimous in telling us X, an agreement that suggests that this version of events must be an accurate account. Having said that, the archaeology tells a different story.”

20. By contrast/in comparison

Usage: Use “by contrast” or “in comparison” when you’re comparing and contrasting pieces of evidence. Example: “Scholar A’s opinion, then, is based on insufficient evidence. By contrast, Scholar B’s opinion seems more plausible.”

21. Then again

Usage: Use this to cast doubt on an assertion. Example: “Writer A asserts that this was the reason for what happened. Then again, it’s possible that he was being paid to say this.”

22. That said

Usage: This is used in the same way as “then again”. Example: “The evidence ostensibly appears to point to this conclusion. That said, much of the evidence is unreliable at best.”

Usage: Use this when you want to introduce a contrasting idea. Example: “Much of scholarship has focused on this evidence. Yet not everyone agrees that this is the most important aspect of the situation.”

Adding a proviso or acknowledging reservations

Sometimes, you may need to acknowledge a shortfalling in a piece of evidence, or add a proviso. Here are some ways of doing so.

24. Despite this

Usage: Use “despite this” or “in spite of this” when you want to outline a point that stands regardless of a shortfalling in the evidence. Example: “The sample size was small, but the results were important despite this.”

25. With this in mind

Usage: Use this when you want your reader to consider a point in the knowledge of something else. Example: “We’ve seen that the methods used in the 19th century study did not always live up to the rigorous standards expected in scientific research today, which makes it difficult to draw definite conclusions. With this in mind, let’s look at a more recent study to see how the results compare.”

26. Provided that

Usage: This means “on condition that”. You can also say “providing that” or just “providing” to mean the same thing. Example: “We may use this as evidence to support our argument, provided that we bear in mind the limitations of the methods used to obtain it.”

27. In view of/in light of

Usage: These phrases are used when something has shed light on something else. Example: “In light of the evidence from the 2013 study, we have a better understanding of…”

28. Nonetheless

Usage: This is similar to “despite this”. Example: “The study had its limitations, but it was nonetheless groundbreaking for its day.”

29. Nevertheless

Usage: This is the same as “nonetheless”. Example: “The study was flawed, but it was important nevertheless.”

30. Notwithstanding

Usage: This is another way of saying “nonetheless”. Example: “Notwithstanding the limitations of the methodology used, it was an important study in the development of how we view the workings of the human mind.”

Giving examples

Good essays always back up points with examples, but it’s going to get boring if you use the expression “for example” every time. Here are a couple of other ways of saying the same thing.

31. For instance

Example: “Some birds migrate to avoid harsher winter climates. Swallows, for instance, leave the UK in early winter and fly south…”

32. To give an illustration

Example: “To give an illustration of what I mean, let’s look at the case of…”

Signifying importance

When you want to demonstrate that a point is particularly important, there are several ways of highlighting it as such.

33. Significantly

Usage: Used to introduce a point that is loaded with meaning that might not be immediately apparent. Example: “Significantly, Tacitus omits to tell us the kind of gossip prevalent in Suetonius’ accounts of the same period.”

34. Notably

Usage: This can be used to mean “significantly” (as above), and it can also be used interchangeably with “in particular” (the example below demonstrates the first of these ways of using it). Example: “Actual figures are notably absent from Scholar A’s analysis.”

35. Importantly

Usage: Use “importantly” interchangeably with “significantly”. Example: “Importantly, Scholar A was being employed by X when he wrote this work, and was presumably therefore under pressure to portray the situation more favourably than he perhaps might otherwise have done.”

Summarising

You’ve almost made it to the end of the essay, but your work isn’t over yet. You need to end by wrapping up everything you’ve talked about, showing that you’ve considered the arguments on both sides and reached the most likely conclusion. Here are some words and phrases to help you.

36. In conclusion

Usage: Typically used to introduce the concluding paragraph or sentence of an essay, summarising what you’ve discussed in a broad overview. Example: “In conclusion, the evidence points almost exclusively to Argument A.”

37. Above all

Usage: Used to signify what you believe to be the most significant point, and the main takeaway from the essay. Example: “Above all, it seems pertinent to remember that…”

38. Persuasive

Usage: This is a useful word to use when summarising which argument you find most convincing. Example: “Scholar A’s point – that Constanze Mozart was motivated by financial gain – seems to me to be the most persuasive argument for her actions following Mozart’s death.”

39. Compelling

Usage: Use in the same way as “persuasive” above. Example: “The most compelling argument is presented by Scholar A.”

40. All things considered

Usage: This means “taking everything into account”. Example: “All things considered, it seems reasonable to assume that…”

How many of these words and phrases will you get into your next essay? And are any of your favourite essay terms missing from our list? Let us know in the comments below, or get in touch here to find out more about courses that can help you with your essays.

At Oxford Royale Academy, we offer a number of summer school courses for young people who are keen to improve their essay writing skills. Click here to apply for one of our courses today, including law , business , medicine and engineering .

Comments are closed.

Choose Your Test

Sat / act prep online guides and tips, 3 strong argumentative essay examples, analyzed.

General Education

Need to defend your opinion on an issue? Argumentative essays are one of the most popular types of essays you’ll write in school. They combine persuasive arguments with fact-based research, and, when done well, can be powerful tools for making someone agree with your point of view. If you’re struggling to write an argumentative essay or just want to learn more about them, seeing examples can be a big help.

After giving an overview of this type of essay, we provide three argumentative essay examples. After each essay, we explain in-depth how the essay was structured, what worked, and where the essay could be improved. We end with tips for making your own argumentative essay as strong as possible.

What Is an Argumentative Essay?

An argumentative essay is an essay that uses evidence and facts to support the claim it’s making. Its purpose is to persuade the reader to agree with the argument being made.

A good argumentative essay will use facts and evidence to support the argument, rather than just the author’s thoughts and opinions. For example, say you wanted to write an argumentative essay stating that Charleston, SC is a great destination for families. You couldn’t just say that it’s a great place because you took your family there and enjoyed it. For it to be an argumentative essay, you need to have facts and data to support your argument, such as the number of child-friendly attractions in Charleston, special deals you can get with kids, and surveys of people who visited Charleston as a family and enjoyed it. The first argument is based entirely on feelings, whereas the second is based on evidence that can be proven.

The standard five paragraph format is common, but not required, for argumentative essays. These essays typically follow one of two formats: the Toulmin model or the Rogerian model.

- The Toulmin model is the most common. It begins with an introduction, follows with a thesis/claim, and gives data and evidence to support that claim. This style of essay also includes rebuttals of counterarguments.

- The Rogerian model analyzes two sides of an argument and reaches a conclusion after weighing the strengths and weaknesses of each.

3 Good Argumentative Essay Examples + Analysis

Below are three examples of argumentative essays, written by yours truly in my school days, as well as analysis of what each did well and where it could be improved.

Argumentative Essay Example 1

Proponents of this idea state that it will save local cities and towns money because libraries are expensive to maintain. They also believe it will encourage more people to read because they won’t have to travel to a library to get a book; they can simply click on what they want to read and read it from wherever they are. They could also access more materials because libraries won’t have to buy physical copies of books; they can simply rent out as many digital copies as they need.

However, it would be a serious mistake to replace libraries with tablets. First, digital books and resources are associated with less learning and more problems than print resources. A study done on tablet vs book reading found that people read 20-30% slower on tablets, retain 20% less information, and understand 10% less of what they read compared to people who read the same information in print. Additionally, staring too long at a screen has been shown to cause numerous health problems, including blurred vision, dizziness, dry eyes, headaches, and eye strain, at much higher instances than reading print does. People who use tablets and mobile devices excessively also have a higher incidence of more serious health issues such as fibromyalgia, shoulder and back pain, carpal tunnel syndrome, and muscle strain. I know that whenever I read from my e-reader for too long, my eyes begin to feel tired and my neck hurts. We should not add to these problems by giving people, especially young people, more reasons to look at screens.

Second, it is incredibly narrow-minded to assume that the only service libraries offer is book lending. Libraries have a multitude of benefits, and many are only available if the library has a physical location. Some of these benefits include acting as a quiet study space, giving people a way to converse with their neighbors, holding classes on a variety of topics, providing jobs, answering patron questions, and keeping the community connected. One neighborhood found that, after a local library instituted community events such as play times for toddlers and parents, job fairs for teenagers, and meeting spaces for senior citizens, over a third of residents reported feeling more connected to their community. Similarly, a Pew survey conducted in 2015 found that nearly two-thirds of American adults feel that closing their local library would have a major impact on their community. People see libraries as a way to connect with others and get their questions answered, benefits tablets can’t offer nearly as well or as easily.

While replacing libraries with tablets may seem like a simple solution, it would encourage people to spend even more time looking at digital screens, despite the myriad issues surrounding them. It would also end access to many of the benefits of libraries that people have come to rely on. In many areas, libraries are such an important part of the community network that they could never be replaced by a simple object.

The author begins by giving an overview of the counter-argument, then the thesis appears as the first sentence in the third paragraph. The essay then spends the rest of the paper dismantling the counter argument and showing why readers should believe the other side.

What this essay does well:

- Although it’s a bit unusual to have the thesis appear fairly far into the essay, it works because, once the thesis is stated, the rest of the essay focuses on supporting it since the counter-argument has already been discussed earlier in the paper.

- This essay includes numerous facts and cites studies to support its case. By having specific data to rely on, the author’s argument is stronger and readers will be more inclined to agree with it.

- For every argument the other side makes, the author makes sure to refute it and follow up with why her opinion is the stronger one. In order to make a strong argument, it’s important to dismantle the other side, which this essay does this by making the author's view appear stronger.

- This is a shorter paper, and if it needed to be expanded to meet length requirements, it could include more examples and go more into depth with them, such as by explaining specific cases where people benefited from local libraries.

- Additionally, while the paper uses lots of data, the author also mentions their own experience with using tablets. This should be removed since argumentative essays focus on facts and data to support an argument, not the author’s own opinion or experiences. Replacing that with more data on health issues associated with screen time would strengthen the essay.

- Some of the points made aren't completely accurate , particularly the one about digital books being cheaper. It actually often costs a library more money to rent out numerous digital copies of a book compared to buying a single physical copy. Make sure in your own essay you thoroughly research each of the points and rebuttals you make, otherwise you'll look like you don't know the issue that well.

Argumentative Essay Example 2

There are multiple drugs available to treat malaria, and many of them work well and save lives, but malaria eradication programs that focus too much on them and not enough on prevention haven’t seen long-term success in Sub-Saharan Africa. A major program to combat malaria was WHO’s Global Malaria Eradication Programme. Started in 1955, it had a goal of eliminating malaria in Africa within the next ten years. Based upon previously successful programs in Brazil and the United States, the program focused mainly on vector control. This included widely distributing chloroquine and spraying large amounts of DDT. More than one billion dollars was spent trying to abolish malaria. However, the program suffered from many problems and in 1969, WHO was forced to admit that the program had not succeeded in eradicating malaria. The number of people in Sub-Saharan Africa who contracted malaria as well as the number of malaria deaths had actually increased over 10% during the time the program was active.

One of the major reasons for the failure of the project was that it set uniform strategies and policies. By failing to consider variations between governments, geography, and infrastructure, the program was not nearly as successful as it could have been. Sub-Saharan Africa has neither the money nor the infrastructure to support such an elaborate program, and it couldn’t be run the way it was meant to. Most African countries don't have the resources to send all their people to doctors and get shots, nor can they afford to clear wetlands or other malaria prone areas. The continent’s spending per person for eradicating malaria was just a quarter of what Brazil spent. Sub-Saharan Africa simply can’t rely on a plan that requires more money, infrastructure, and expertise than they have to spare.

Additionally, the widespread use of chloroquine has created drug resistant parasites which are now plaguing Sub-Saharan Africa. Because chloroquine was used widely but inconsistently, mosquitoes developed resistance, and chloroquine is now nearly completely ineffective in Sub-Saharan Africa, with over 95% of mosquitoes resistant to it. As a result, newer, more expensive drugs need to be used to prevent and treat malaria, which further drives up the cost of malaria treatment for a region that can ill afford it.

Instead of developing plans to treat malaria after the infection has incurred, programs should focus on preventing infection from occurring in the first place. Not only is this plan cheaper and more effective, reducing the number of people who contract malaria also reduces loss of work/school days which can further bring down the productivity of the region.

One of the cheapest and most effective ways of preventing malaria is to implement insecticide-treated bed nets (ITNs). These nets provide a protective barrier around the person or people using them. While untreated bed nets are still helpful, those treated with insecticides are much more useful because they stop mosquitoes from biting people through the nets, and they help reduce mosquito populations in a community, thus helping people who don’t even own bed nets. Bed nets are also very effective because most mosquito bites occur while the person is sleeping, so bed nets would be able to drastically reduce the number of transmissions during the night. In fact, transmission of malaria can be reduced by as much as 90% in areas where the use of ITNs is widespread. Because money is so scarce in Sub-Saharan Africa, the low cost is a great benefit and a major reason why the program is so successful. Bed nets cost roughly 2 USD to make, last several years, and can protect two adults. Studies have shown that, for every 100-1000 more nets are being used, one less child dies of malaria. With an estimated 300 million people in Africa not being protected by mosquito nets, there’s the potential to save three million lives by spending just a few dollars per person.

Reducing the number of people who contract malaria would also reduce poverty levels in Africa significantly, thus improving other aspects of society like education levels and the economy. Vector control is more effective than treatment strategies because it means fewer people are getting sick. When fewer people get sick, the working population is stronger as a whole because people are not put out of work from malaria, nor are they caring for sick relatives. Malaria-afflicted families can typically only harvest 40% of the crops that healthy families can harvest. Additionally, a family with members who have malaria spends roughly a quarter of its income treatment, not including the loss of work they also must deal with due to the illness. It’s estimated that malaria costs Africa 12 billion USD in lost income every year. A strong working population creates a stronger economy, which Sub-Saharan Africa is in desperate need of.

This essay begins with an introduction, which ends with the thesis (that malaria eradication plans in Sub-Saharan Africa should focus on prevention rather than treatment). The first part of the essay lays out why the counter argument (treatment rather than prevention) is not as effective, and the second part of the essay focuses on why prevention of malaria is the better path to take.

- The thesis appears early, is stated clearly, and is supported throughout the rest of the essay. This makes the argument clear for readers to understand and follow throughout the essay.

- There’s lots of solid research in this essay, including specific programs that were conducted and how successful they were, as well as specific data mentioned throughout. This evidence helps strengthen the author’s argument.

- The author makes a case for using expanding bed net use over waiting until malaria occurs and beginning treatment, but not much of a plan is given for how the bed nets would be distributed or how to ensure they’re being used properly. By going more into detail of what she believes should be done, the author would be making a stronger argument.

- The introduction of the essay does a good job of laying out the seriousness of the problem, but the conclusion is short and abrupt. Expanding it into its own paragraph would give the author a final way to convince readers of her side of the argument.

Argumentative Essay Example 3

There are many ways payments could work. They could be in the form of a free-market approach, where athletes are able to earn whatever the market is willing to pay them, it could be a set amount of money per athlete, or student athletes could earn income from endorsements, autographs, and control of their likeness, similar to the way top Olympians earn money.

Proponents of the idea believe that, because college athletes are the ones who are training, participating in games, and bringing in audiences, they should receive some sort of compensation for their work. If there were no college athletes, the NCAA wouldn’t exist, college coaches wouldn’t receive there (sometimes very high) salaries, and brands like Nike couldn’t profit from college sports. In fact, the NCAA brings in roughly $1 billion in revenue a year, but college athletes don’t receive any of that money in the form of a paycheck. Additionally, people who believe college athletes should be paid state that paying college athletes will actually encourage them to remain in college longer and not turn pro as quickly, either by giving them a way to begin earning money in college or requiring them to sign a contract stating they’ll stay at the university for a certain number of years while making an agreed-upon salary.

Supporters of this idea point to Zion Williamson, the Duke basketball superstar, who, during his freshman year, sustained a serious knee injury. Many argued that, even if he enjoyed playing for Duke, it wasn’t worth risking another injury and ending his professional career before it even began for a program that wasn’t paying him. Williamson seems to have agreed with them and declared his eligibility for the NCAA draft later that year. If he was being paid, he may have stayed at Duke longer. In fact, roughly a third of student athletes surveyed stated that receiving a salary while in college would make them “strongly consider” remaining collegiate athletes longer before turning pro.

Paying athletes could also stop the recruitment scandals that have plagued the NCAA. In 2018, the NCAA stripped the University of Louisville's men's basketball team of its 2013 national championship title because it was discovered coaches were using sex workers to entice recruits to join the team. There have been dozens of other recruitment scandals where college athletes and recruits have been bribed with anything from having their grades changed, to getting free cars, to being straight out bribed. By paying college athletes and putting their salaries out in the open, the NCAA could end the illegal and underhanded ways some schools and coaches try to entice athletes to join.

People who argue against the idea of paying college athletes believe the practice could be disastrous for college sports. By paying athletes, they argue, they’d turn college sports into a bidding war, where only the richest schools could afford top athletes, and the majority of schools would be shut out from developing a talented team (though some argue this already happens because the best players often go to the most established college sports programs, who typically pay their coaches millions of dollars per year). It could also ruin the tight camaraderie of many college teams if players become jealous that certain teammates are making more money than they are.

They also argue that paying college athletes actually means only a small fraction would make significant money. Out of the 350 Division I athletic departments, fewer than a dozen earn any money. Nearly all the money the NCAA makes comes from men’s football and basketball, so paying college athletes would make a small group of men--who likely will be signed to pro teams and begin making millions immediately out of college--rich at the expense of other players.

Those against paying college athletes also believe that the athletes are receiving enough benefits already. The top athletes already receive scholarships that are worth tens of thousands per year, they receive free food/housing/textbooks, have access to top medical care if they are injured, receive top coaching, get travel perks and free gear, and can use their time in college as a way to capture the attention of professional recruiters. No other college students receive anywhere near as much from their schools.

People on this side also point out that, while the NCAA brings in a massive amount of money each year, it is still a non-profit organization. How? Because over 95% of those profits are redistributed to its members’ institutions in the form of scholarships, grants, conferences, support for Division II and Division III teams, and educational programs. Taking away a significant part of that revenue would hurt smaller programs that rely on that money to keep running.

While both sides have good points, it’s clear that the negatives of paying college athletes far outweigh the positives. College athletes spend a significant amount of time and energy playing for their school, but they are compensated for it by the scholarships and perks they receive. Adding a salary to that would result in a college athletic system where only a small handful of athletes (those likely to become millionaires in the professional leagues) are paid by a handful of schools who enter bidding wars to recruit them, while the majority of student athletics and college athletic programs suffer or even shut down for lack of money. Continuing to offer the current level of benefits to student athletes makes it possible for as many people to benefit from and enjoy college sports as possible.

This argumentative essay follows the Rogerian model. It discusses each side, first laying out multiple reasons people believe student athletes should be paid, then discussing reasons why the athletes shouldn’t be paid. It ends by stating that college athletes shouldn’t be paid by arguing that paying them would destroy college athletics programs and cause them to have many of the issues professional sports leagues have.

- Both sides of the argument are well developed, with multiple reasons why people agree with each side. It allows readers to get a full view of the argument and its nuances.

- Certain statements on both sides are directly rebuffed in order to show where the strengths and weaknesses of each side lie and give a more complete and sophisticated look at the argument.

- Using the Rogerian model can be tricky because oftentimes you don’t explicitly state your argument until the end of the paper. Here, the thesis doesn’t appear until the first sentence of the final paragraph. That doesn’t give readers a lot of time to be convinced that your argument is the right one, compared to a paper where the thesis is stated in the beginning and then supported throughout the paper. This paper could be strengthened if the final paragraph was expanded to more fully explain why the author supports the view, or if the paper had made it clearer that paying athletes was the weaker argument throughout.

3 Tips for Writing a Good Argumentative Essay

Now that you’ve seen examples of what good argumentative essay samples look like, follow these three tips when crafting your own essay.

#1: Make Your Thesis Crystal Clear

The thesis is the key to your argumentative essay; if it isn’t clear or readers can’t find it easily, your entire essay will be weak as a result. Always make sure that your thesis statement is easy to find. The typical spot for it is the final sentence of the introduction paragraph, but if it doesn’t fit in that spot for your essay, try to at least put it as the first or last sentence of a different paragraph so it stands out more.

Also make sure that your thesis makes clear what side of the argument you’re on. After you’ve written it, it’s a great idea to show your thesis to a couple different people--classmates are great for this. Just by reading your thesis they should be able to understand what point you’ll be trying to make with the rest of your essay.

#2: Show Why the Other Side Is Weak

When writing your essay, you may be tempted to ignore the other side of the argument and just focus on your side, but don’t do this. The best argumentative essays really tear apart the other side to show why readers shouldn’t believe it. Before you begin writing your essay, research what the other side believes, and what their strongest points are. Then, in your essay, be sure to mention each of these and use evidence to explain why they’re incorrect/weak arguments. That’ll make your essay much more effective than if you only focused on your side of the argument.

#3: Use Evidence to Support Your Side

Remember, an essay can’t be an argumentative essay if it doesn’t support its argument with evidence. For every point you make, make sure you have facts to back it up. Some examples are previous studies done on the topic, surveys of large groups of people, data points, etc. There should be lots of numbers in your argumentative essay that support your side of the argument. This will make your essay much stronger compared to only relying on your own opinions to support your argument.

Summary: Argumentative Essay Sample

Argumentative essays are persuasive essays that use facts and evidence to support their side of the argument. Most argumentative essays follow either the Toulmin model or the Rogerian model. By reading good argumentative essay examples, you can learn how to develop your essay and provide enough support to make readers agree with your opinion. When writing your essay, remember to always make your thesis clear, show where the other side is weak, and back up your opinion with data and evidence.

What's Next?

Do you need to write an argumentative essay as well? Check out our guide on the best argumentative essay topics for ideas!

You'll probably also need to write research papers for school. We've got you covered with 113 potential topics for research papers.

Your college admissions essay may end up being one of the most important essays you write. Follow our step-by-step guide on writing a personal statement to have an essay that'll impress colleges.

Christine graduated from Michigan State University with degrees in Environmental Biology and Geography and received her Master's from Duke University. In high school she scored in the 99th percentile on the SAT and was named a National Merit Finalist. She has taught English and biology in several countries.

Student and Parent Forum

Our new student and parent forum, at ExpertHub.PrepScholar.com , allow you to interact with your peers and the PrepScholar staff. See how other students and parents are navigating high school, college, and the college admissions process. Ask questions; get answers.

Ask a Question Below

Have any questions about this article or other topics? Ask below and we'll reply!

Improve With Our Famous Guides

- For All Students

The 5 Strategies You Must Be Using to Improve 160+ SAT Points

How to Get a Perfect 1600, by a Perfect Scorer

Series: How to Get 800 on Each SAT Section:

Score 800 on SAT Math

Score 800 on SAT Reading

Score 800 on SAT Writing

Series: How to Get to 600 on Each SAT Section:

Score 600 on SAT Math

Score 600 on SAT Reading

Score 600 on SAT Writing

Free Complete Official SAT Practice Tests

What SAT Target Score Should You Be Aiming For?

15 Strategies to Improve Your SAT Essay

The 5 Strategies You Must Be Using to Improve 4+ ACT Points

How to Get a Perfect 36 ACT, by a Perfect Scorer

Series: How to Get 36 on Each ACT Section:

36 on ACT English

36 on ACT Math

36 on ACT Reading

36 on ACT Science

Series: How to Get to 24 on Each ACT Section:

24 on ACT English

24 on ACT Math

24 on ACT Reading

24 on ACT Science

What ACT target score should you be aiming for?

ACT Vocabulary You Must Know

ACT Writing: 15 Tips to Raise Your Essay Score

How to Get Into Harvard and the Ivy League

How to Get a Perfect 4.0 GPA

How to Write an Amazing College Essay

What Exactly Are Colleges Looking For?

Is the ACT easier than the SAT? A Comprehensive Guide

Should you retake your SAT or ACT?

When should you take the SAT or ACT?

Stay Informed

Get the latest articles and test prep tips!

Looking for Graduate School Test Prep?

Check out our top-rated graduate blogs here:

GRE Online Prep Blog

GMAT Online Prep Blog

TOEFL Online Prep Blog

Holly R. "I am absolutely overjoyed and cannot thank you enough for helping me!”

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

- How to write an argumentative essay | Examples & tips

How to Write an Argumentative Essay | Examples & Tips

Published on July 24, 2020 by Jack Caulfield . Revised on July 23, 2023.

An argumentative essay expresses an extended argument for a particular thesis statement . The author takes a clearly defined stance on their subject and builds up an evidence-based case for it.

Instantly correct all language mistakes in your text

Upload your document to correct all your mistakes in minutes

Table of contents

When do you write an argumentative essay, approaches to argumentative essays, introducing your argument, the body: developing your argument, concluding your argument, other interesting articles, frequently asked questions about argumentative essays.

You might be assigned an argumentative essay as a writing exercise in high school or in a composition class. The prompt will often ask you to argue for one of two positions, and may include terms like “argue” or “argument.” It will frequently take the form of a question.

The prompt may also be more open-ended in terms of the possible arguments you could make.

Argumentative writing at college level

At university, the vast majority of essays or papers you write will involve some form of argumentation. For example, both rhetorical analysis and literary analysis essays involve making arguments about texts.

In this context, you won’t necessarily be told to write an argumentative essay—but making an evidence-based argument is an essential goal of most academic writing, and this should be your default approach unless you’re told otherwise.

Examples of argumentative essay prompts

At a university level, all the prompts below imply an argumentative essay as the appropriate response.

Your research should lead you to develop a specific position on the topic. The essay then argues for that position and aims to convince the reader by presenting your evidence, evaluation and analysis.

- Don’t just list all the effects you can think of.

- Do develop a focused argument about the overall effect and why it matters, backed up by evidence from sources.

- Don’t just provide a selection of data on the measures’ effectiveness.

- Do build up your own argument about which kinds of measures have been most or least effective, and why.

- Don’t just analyze a random selection of doppelgänger characters.

- Do form an argument about specific texts, comparing and contrasting how they express their thematic concerns through doppelgänger characters.

Prevent plagiarism. Run a free check.

An argumentative essay should be objective in its approach; your arguments should rely on logic and evidence, not on exaggeration or appeals to emotion.

There are many possible approaches to argumentative essays, but there are two common models that can help you start outlining your arguments: The Toulmin model and the Rogerian model.

Toulmin arguments

The Toulmin model consists of four steps, which may be repeated as many times as necessary for the argument:

- Make a claim

- Provide the grounds (evidence) for the claim

- Explain the warrant (how the grounds support the claim)

- Discuss possible rebuttals to the claim, identifying the limits of the argument and showing that you have considered alternative perspectives

The Toulmin model is a common approach in academic essays. You don’t have to use these specific terms (grounds, warrants, rebuttals), but establishing a clear connection between your claims and the evidence supporting them is crucial in an argumentative essay.

Say you’re making an argument about the effectiveness of workplace anti-discrimination measures. You might:

- Claim that unconscious bias training does not have the desired results, and resources would be better spent on other approaches

- Cite data to support your claim

- Explain how the data indicates that the method is ineffective

- Anticipate objections to your claim based on other data, indicating whether these objections are valid, and if not, why not.

Rogerian arguments

The Rogerian model also consists of four steps you might repeat throughout your essay:

- Discuss what the opposing position gets right and why people might hold this position

- Highlight the problems with this position

- Present your own position , showing how it addresses these problems

- Suggest a possible compromise —what elements of your position would proponents of the opposing position benefit from adopting?

This model builds up a clear picture of both sides of an argument and seeks a compromise. It is particularly useful when people tend to disagree strongly on the issue discussed, allowing you to approach opposing arguments in good faith.

Say you want to argue that the internet has had a positive impact on education. You might:

- Acknowledge that students rely too much on websites like Wikipedia

- Argue that teachers view Wikipedia as more unreliable than it really is

- Suggest that Wikipedia’s system of citations can actually teach students about referencing

- Suggest critical engagement with Wikipedia as a possible assignment for teachers who are skeptical of its usefulness.

You don’t necessarily have to pick one of these models—you may even use elements of both in different parts of your essay—but it’s worth considering them if you struggle to structure your arguments.

Regardless of which approach you take, your essay should always be structured using an introduction , a body , and a conclusion .

Like other academic essays, an argumentative essay begins with an introduction . The introduction serves to capture the reader’s interest, provide background information, present your thesis statement , and (in longer essays) to summarize the structure of the body.

Hover over different parts of the example below to see how a typical introduction works.

The spread of the internet has had a world-changing effect, not least on the world of education. The use of the internet in academic contexts is on the rise, and its role in learning is hotly debated. For many teachers who did not grow up with this technology, its effects seem alarming and potentially harmful. This concern, while understandable, is misguided. The negatives of internet use are outweighed by its critical benefits for students and educators—as a uniquely comprehensive and accessible information source; a means of exposure to and engagement with different perspectives; and a highly flexible learning environment.

The body of an argumentative essay is where you develop your arguments in detail. Here you’ll present evidence, analysis, and reasoning to convince the reader that your thesis statement is true.

In the standard five-paragraph format for short essays, the body takes up three of your five paragraphs. In longer essays, it will be more paragraphs, and might be divided into sections with headings.

Each paragraph covers its own topic, introduced with a topic sentence . Each of these topics must contribute to your overall argument; don’t include irrelevant information.

This example paragraph takes a Rogerian approach: It first acknowledges the merits of the opposing position and then highlights problems with that position.

Hover over different parts of the example to see how a body paragraph is constructed.

A common frustration for teachers is students’ use of Wikipedia as a source in their writing. Its prevalence among students is not exaggerated; a survey found that the vast majority of the students surveyed used Wikipedia (Head & Eisenberg, 2010). An article in The Guardian stresses a common objection to its use: “a reliance on Wikipedia can discourage students from engaging with genuine academic writing” (Coomer, 2013). Teachers are clearly not mistaken in viewing Wikipedia usage as ubiquitous among their students; but the claim that it discourages engagement with academic sources requires further investigation. This point is treated as self-evident by many teachers, but Wikipedia itself explicitly encourages students to look into other sources. Its articles often provide references to academic publications and include warning notes where citations are missing; the site’s own guidelines for research make clear that it should be used as a starting point, emphasizing that users should always “read the references and check whether they really do support what the article says” (“Wikipedia:Researching with Wikipedia,” 2020). Indeed, for many students, Wikipedia is their first encounter with the concepts of citation and referencing. The use of Wikipedia therefore has a positive side that merits deeper consideration than it often receives.

Receive feedback on language, structure, and formatting

Professional editors proofread and edit your paper by focusing on:

- Academic style

- Vague sentences

- Style consistency

See an example

An argumentative essay ends with a conclusion that summarizes and reflects on the arguments made in the body.

No new arguments or evidence appear here, but in longer essays you may discuss the strengths and weaknesses of your argument and suggest topics for future research. In all conclusions, you should stress the relevance and importance of your argument.

Hover over the following example to see the typical elements of a conclusion.

The internet has had a major positive impact on the world of education; occasional pitfalls aside, its value is evident in numerous applications. The future of teaching lies in the possibilities the internet opens up for communication, research, and interactivity. As the popularity of distance learning shows, students value the flexibility and accessibility offered by digital education, and educators should fully embrace these advantages. The internet’s dangers, real and imaginary, have been documented exhaustively by skeptics, but the internet is here to stay; it is time to focus seriously on its potential for good.

If you want to know more about AI tools , college essays , or fallacies make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples or go directly to our tools!

- Ad hominem fallacy

- Post hoc fallacy

- Appeal to authority fallacy

- False cause fallacy

- Sunk cost fallacy

College essays

- Choosing Essay Topic

- Write a College Essay

- Write a Diversity Essay

- College Essay Format & Structure

- Comparing and Contrasting in an Essay

(AI) Tools

- Grammar Checker

- Paraphrasing Tool

- Text Summarizer

- AI Detector

- Plagiarism Checker

- Citation Generator

An argumentative essay tends to be a longer essay involving independent research, and aims to make an original argument about a topic. Its thesis statement makes a contentious claim that must be supported in an objective, evidence-based way.

An expository essay also aims to be objective, but it doesn’t have to make an original argument. Rather, it aims to explain something (e.g., a process or idea) in a clear, concise way. Expository essays are often shorter assignments and rely less on research.

At college level, you must properly cite your sources in all essays , research papers , and other academic texts (except exams and in-class exercises).

Add a citation whenever you quote , paraphrase , or summarize information or ideas from a source. You should also give full source details in a bibliography or reference list at the end of your text.

The exact format of your citations depends on which citation style you are instructed to use. The most common styles are APA , MLA , and Chicago .

The majority of the essays written at university are some sort of argumentative essay . Unless otherwise specified, you can assume that the goal of any essay you’re asked to write is argumentative: To convince the reader of your position using evidence and reasoning.

In composition classes you might be given assignments that specifically test your ability to write an argumentative essay. Look out for prompts including instructions like “argue,” “assess,” or “discuss” to see if this is the goal.

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

Caulfield, J. (2023, July 23). How to Write an Argumentative Essay | Examples & Tips. Scribbr. Retrieved April 9, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/academic-essay/argumentative-essay/

Is this article helpful?

Jack Caulfield

Other students also liked, how to write a thesis statement | 4 steps & examples, how to write topic sentences | 4 steps, examples & purpose, how to write an expository essay, "i thought ai proofreading was useless but..".

I've been using Scribbr for years now and I know it's a service that won't disappoint. It does a good job spotting mistakes”

What are your chances of acceptance?

Calculate for all schools, your chance of acceptance.

Your chancing factors

Extracurriculars.

52 Argumentative Essay Ideas that are Actually Interesting

What’s covered:, how to pick a good argumentative essay topic, elements of a strong argumentative essay, argumentative essay idea example topics.

Are you having writer’s block? Coming up with an essay topic can be the hardest part of the process. You have very likely encountered argumentative essay writing in high school and have been asked to write your own. If you’re having trouble finding a topic, we’ve created a list of 52 essay ideas to help jumpstart your brainstorming process! In addition, this post will cover strategies for picking a topic and how to make your argument a strong one. Ultimately, the goal is to convince your reader.

An argumentative essay tasks the writer with presenting an assertion and bolstering that assertion with proper research. You’ll present the claim’s authenticity. This means that whatever argument you’re making must be empirically true! Writing an argumentative essay without any evidence will leave you stranded without any facts to back up your claim. When choosing your essay topic, begin by thinking about themes that have been researched before. Readers will be more engaged with an argument that is supported by data.

This isn’t to say that your argumentative essay topic has to be as well-known, like “Gravity: Does it Exist?” but it shouldn’t be so obscure that there isn’t ample evidence. Finding a topic with multiple sources confirming its validity will help you support your thesis throughout your essay. If upon review of these articles you begin to doubt their worth due to small sample sizes, biased funding sources, or scientific disintegrity, don’t be afraid to move on to a different topic. Your ultimate goal should be proving to your audience that your argument is true because the data supports it.

The hardest essays to write are the ones that you don’t care about. If you don’t care about your topic, why should someone else? Topics that are more personal to the reader are immediately more thoughtful and meaningful because the author’s passion shines through. If you are free to choose an argumentative essay topic, find a topic where the papers you read and cite are fun to read. It’s much easier to write when the passion is already inside of you!

However, you won’t always have the choice to pick your topic. You may receive an assignment to write an argumentative essay that you feel is boring. There is still value in writing an argumentative essay on a topic that may not be of interest to you. It will push you to study a new topic, and broaden your ability to write on a variety of topics. Getting good at proving a point thoroughly and effectively will help you to both understand different fields more completely and increase your comfort with scientific writing.

Convincing Thesis Statement

It’s important to remember the general essay structure: an introduction paragraph with a thesis statement, body paragraphs, and a conclusion. A strong thesis statement will set your essay up for success. What is it? A succinct, concise, and pithy sentence found in your first paragraph that summarizes your main point. Pour over this statement to ensure that you can set up your reader to understand your essay. You should also restate your thesis throughout your essay to keep your reader focused on your point.

Ample Research

A typical argumentative essay prompt may look like this: “What has been the most important invention of the 21st century? Support your claim with evidence.” This question is open-ended and gives you flexibility. But that also means it requires research to prove your point convincingly. The strongest essays weave scientific quotes and results into your writing. You can use recent articles, primary sources, or news sources. Maybe you even cite your own research. Remember, this process takes time, so be sure you set aside enough time to dive deep into your topic.

Clear Structure

If the reader can’t follow your argument, all your research could be for nothing! Structure is key to persuading your audience. Below are two common argumentative essay structures that you can use to organize your essays.

The Toulmin argument and the Rogerian argument each contain the four sections mentioned above but executes them in different ways. Be sure to familiarize yourself with both essay structures so that your essay is the most effective it can be.

The Toulmin argument has a straightforward presentation. You begin with your assertion, your thesis statement. You then list the evidence that supports your point and why these are valid sources. The bulk of your essay should be explaining how your sources support your claim. You then end your essay by acknowledging and discussing the problems or flaws that readers may find in your presentation. Then, you should list the solutions to these and alternative perspectives and prove your argument is stronger.

The Rogerian argument has a more complex structure. You begin with a discussion of what opposing sides do right and the validity of their arguments. This is effective because it allows you to piece apart your opponent’s argument. The next section contains your position on the questions. In this section, it is important to list problems with your opponent’s argument that your argument fixes. This way, your position feels much stronger. Your essay ends with suggesting a possible compromise between the two sides. A combination of the two sides could be the most effective solution.

- Is the death penalty effective?

- Is our election process fair?

- Is the electoral college outdated?

- Should we have lower taxes?

- How many Supreme Court Justices should there be?

- Should there be different term limits for elected officials?

- Should the drinking age be lowered?

- Does religion cause war?

- Should the country legalize marijuana?

- Should the country have tighter gun control laws?

- Should men get paternity leave?

- Should maternity leave be longer?

- Should smoking be banned?

- Should the government have a say in our diet?

- Should birth control be free?

- Should we increase access to condoms for teens?

- Should abortion be legal?

- Do school uniforms help educational attainment?

- Are kids better or worse students than they were ten years ago?

- Should students be allowed to cheat?

- Is school too long?

- Does school start too early?

- Are there benefits to attending a single-sex school?

- Is summer break still relevant?

- Is college too expensive?

Art / Culture

- How can you reform copyright law?

- What was the best decade for music?

- Do video games cause students to be more violent?

- Should content online be more harshly regulated?

- Should graffiti be considered art or vandalism?

- Should schools ban books?

- How important is art education?

- Should music be taught in school?

- Are music-sharing services helpful to artists?

- What is the best way to teach science in a religious school?

- Should fracking be legal?

- Should parents be allowed to modify their unborn children?

- Should vaccinations be required for attending school?

- Are GMOs helpful or harmful?

- Are we too dependent on our phones?

- Should everyone have internet access?

- Should internet access be free?

- Should the police force be required to wear body cams?

- Should social media companies be allowed to collect data from their users?

- How has the internet impacted human society?

- Should self-driving cars be allowed on the streets?

- Should athletes be held to high moral standards?

- Are professional athletes paid too much?

- Should the U.S. have more professional sports teams?

- Should sports be separated by gender?

- Should college athletes be paid?

- What are the best ways to increase safety in sports?

Where to Get More Argumentative Essay Topic Ideas

If you need more help brainstorming topics, especially those that are personalized to your interests, you can use CollegeVine’s free AI tutor, Ivy . Ivy can help you come up with original argumentative essay ideas, and she can also help with the rest of your homework, from math to languages.

Related CollegeVine Blog Posts

Argumentative Essay Examples to Inspire You (+ Free Formula)

.webp)

Table of contents

Meredith Sell

Have you ever been asked to explain your opinion on a controversial issue?

- Maybe your family got into a discussion about chemical pesticides

- Someone at work argues against investing resources into your project

- Your partner thinks intermittent fasting is the best way to lose weight and you disagree

Proving your point in an argumentative essay can be challenging, unless you are using a proven formula.

Argumentative essay formula & example

In the image below, you can see a recommended structure for argumentative essays. It starts with the topic sentence, which establishes the main idea of the essay. Next, this hypothesis is developed in the development stage. Then, the rebuttal, or the refutal of the main counter argument or arguments. Then, again, development of the rebuttal. This is followed by an example, and ends with a summary. This is a very basic structure, but it gives you a bird-eye-view of how a proper argumentative essay can be built.

Writing an argumentative essay (for a class, a news outlet, or just for fun) can help you improve your understanding of an issue and sharpen your thinking on the matter. Using researched facts and data, you can explain why you or others think the way you do, even while other reasonable people disagree.

Free AI argumentative essay generator > Free AI argumentative essay generator >

What Is an Argumentative Essay?

An argumentative essay is an explanatory essay that takes a side.

Instead of appealing to emotion and personal experience to change the reader’s mind, an argumentative essay uses logic and well-researched factual information to explain why the thesis in question is the most reasonable opinion on the matter.

Over several paragraphs or pages, the author systematically walks through:

- The opposition (and supporting evidence)

- The chosen thesis (and its supporting evidence)

At the end, the author leaves the decision up to the reader, trusting that the case they’ve made will do the work of changing the reader’s mind. Even if the reader’s opinion doesn’t change, they come away from the essay with a greater understanding of the perspective presented — and perhaps a better understanding of their original opinion.

All of that might make it seem like writing an argumentative essay is way harder than an emotionally-driven persuasive essay — but if you’re like me and much more comfortable spouting facts and figures than making impassioned pleas, you may find that an argumentative essay is easier to write.

Plus, the process of researching an argumentative essay means you can check your assumptions and develop an opinion that’s more based in reality than what you originally thought. I know for sure that my opinions need to be fact checked — don’t yours?

So how exactly do we write the argumentative essay?

How do you start an argumentative essay

First, gain a clear understanding of what exactly an argumentative essay is. To formulate a proper topic sentence, you have to be clear on your topic, and to explore it through research.

Students have difficulty starting an essay because the whole task seems intimidating, and they are afraid of spending too much time on the topic sentence. Experienced writers, however, know that there is no set time to spend on figuring out your topic. It's a real exploration that is based to a large extent on intuition.

6 Steps to Write an Argumentative Essay (Persuasion Formula)

Use this checklist to tackle your essay one step at a time:

1. Research an issue with an arguable question

To start, you need to identify an issue that well-informed people have varying opinions on. Here, it’s helpful to think of one core topic and how it intersects with another (or several other) issues. That intersection is where hot takes and reasonable (or unreasonable) opinions abound.

I find it helpful to stage the issue as a question.

For example:

Is it better to legislate the minimum size of chicken enclosures or to outlaw the sale of eggs from chickens who don’t have enough space?

Should snow removal policies focus more on effectively keeping roads clear for traffic or the environmental impacts of snow removal methods?

Once you have your arguable question ready, start researching the basic facts and specific opinions and arguments on the issue. Do your best to stay focused on gathering information that is directly relevant to your topic. Depending on what your essay is for, you may reference academic studies, government reports, or newspaper articles.

Research your opposition and the facts that support their viewpoint as much as you research your own position . You’ll need to address your opposition in your essay, so you’ll want to know their argument from the inside out.

2. Choose a side based on your research

You likely started with an inclination toward one side or the other, but your research should ultimately shape your perspective. So once you’ve completed the research, nail down your opinion and start articulating the what and why of your take.

What: I think it’s better to outlaw selling eggs from chickens whose enclosures are too small.

Why: Because if you regulate the enclosure size directly, egg producers outside of the government’s jurisdiction could ship eggs into your territory and put nearby egg producers out of business by offering better prices because they don’t have the added cost of larger enclosures.

This is an early form of your thesis and the basic logic of your argument. You’ll want to iterate on this a few times and develop a one-sentence statement that sums up the thesis of your essay.

Thesis: Outlawing the sale of eggs from chickens with cramped living spaces is better for business than regulating the size of chicken enclosures.

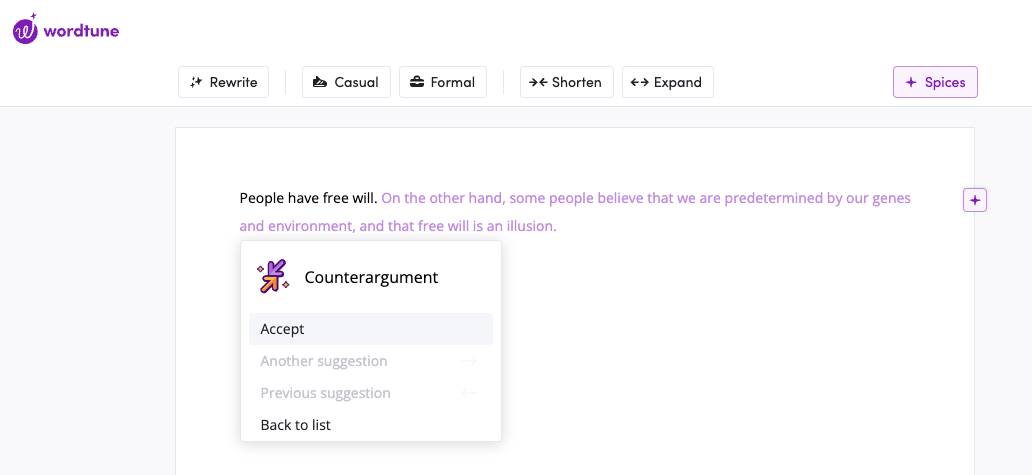

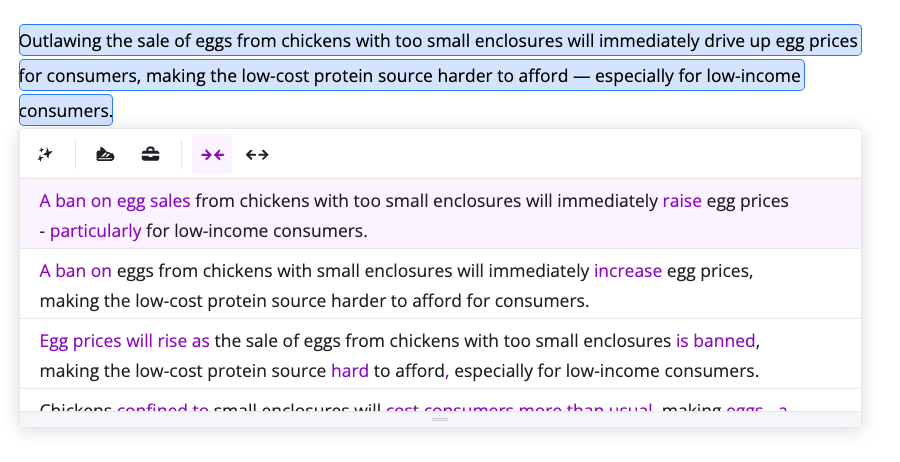

Now that you’ve articulated your thesis , spell out the counterargument(s) as well. Putting your opposition’s take into words will help you throughout the rest of the essay-writing process. (You can start by choosing the counter argument option with Wordtune Spices .)

Counterargument: Outlawing the sale of eggs from chickens with too small enclosures will immediately drive up egg prices for consumers, making the low-cost protein source harder to afford — especially for low-income consumers.

There may be one main counterargument to articulate, or several. Write them all out and start thinking about how you’ll use evidence to address each of them or show why your argument is still the best option.

3. Organize the evidence — for your side and the opposition

You did all of that research for a reason. Now’s the time to use it.

Hopefully, you kept detailed notes in a document, complete with links and titles of all your source material. Go through your research document and copy the evidence for your argument and your opposition’s into another document.

List the main points of your argument. Then, below each point, paste the evidence that backs them up.

If you’re writing about chicken enclosures, maybe you found evidence that shows the spread of disease among birds kept in close quarters is worse than among birds who have more space. Or maybe you found information that says eggs from free-range chickens are more flavorful or nutritious. Put that information next to the appropriate part of your argument.

Repeat the process with your opposition’s argument: What information did you find that supports your opposition? Paste it beside your opposition’s argument.

You could also put information here that refutes your opposition, but organize it in a way that clearly tells you — at a glance — that the information disproves their point.

Counterargument: Outlawing the sale of eggs from chickens with too small enclosures will immediately drive up egg prices for consumers.

BUT: Sicknesses like avian flu spread more easily through small enclosures and could cause a shortage that would drive up egg prices naturally, so ensuring larger enclosures is still a better policy for consumers over the long term.

As you organize your research and see the evidence all together, start thinking through the best way to order your points.

Will it be better to present your argument all at once or to break it up with opposition claims you can quickly refute? Would some points set up other points well? Does a more complicated point require that the reader understands a simpler point first?

Play around and rearrange your notes to see how your essay might flow one way or another.

4. Freewrite or outline to think through your argument

Is your brain buzzing yet? At this point in the process, it can be helpful to take out a notebook or open a fresh document and dump whatever you’re thinking on the page.

Where should your essay start? What ground-level information do you need to provide your readers before you can dive into the issue?

Use your organized evidence document from step 3 to think through your argument from beginning to end, and determine the structure of your essay.

There are three typical structures for argumentative essays:

- Make your argument and tackle opposition claims one by one, as they come up in relation to the points of your argument - In this approach, the whole essay — from beginning to end — focuses on your argument, but as you make each point, you address the relevant opposition claims individually. This approach works well if your opposition’s views can be quickly explained and refuted and if they directly relate to specific points in your argument.

- Make the bulk of your argument, and then address the opposition all at once in a paragraph (or a few) - This approach puts the opposition in its own section, separate from your main argument. After you’ve made your case, with ample evidence to convince your readers, you write about the opposition, explaining their viewpoint and supporting evidence — and showing readers why the opposition’s argument is unconvincing. Once you’ve addressed the opposition, you write a conclusion that sums up why your argument is the better one.

- Open your essay by talking about the opposition and where it falls short. Build your entire argument to show how it is superior to that opposition - With this structure, you’re showing your readers “a better way” to address the issue. After opening your piece by showing how your opposition’s approaches fail, you launch into your argument, providing readers with ample evidence that backs you up.

As you think through your argument and examine your evidence document, consider which structure will serve your argument best. Sketch out an outline to give yourself a map to follow in the writing process. You could also rearrange your evidence document again to match your outline, so it will be easy to find what you need when you start writing.

5. Write your first draft

You have an outline and an organized document with all your points and evidence lined up and ready. Now you just have to write your essay.

In your first draft, focus on getting your ideas on the page. Your wording may not be perfect (whose is?), but you know what you’re trying to say — so even if you’re overly wordy and taking too much space to say what you need to say, put those words on the page.

Follow your outline, and draw from that evidence document to flesh out each point of your argument. Explain what the evidence means for your argument and your opposition. Connect the dots for your readers so they can follow you, point by point, and understand what you’re trying to say.

As you write, be sure to include:

1. Any background information your reader needs in order to understand the issue in question.

2. Evidence for both your argument and the counterargument(s). This shows that you’ve done your homework and builds trust with your reader, while also setting you up to make a more convincing argument. (If you find gaps in your research while you’re writing, Wordtune Spices can source statistics or historical facts on the fly!)

Get Wordtune for free > Get Wordtune for free >

3. A conclusion that sums up your overall argument and evidence — and leaves the reader with an understanding of the issue and its significance. This sort of conclusion brings your essay to a strong ending that doesn’t waste readers’ time, but actually adds value to your case.

6. Revise (with Wordtune)

The hard work is done: you have a first draft. Now, let’s fine tune your writing.

I like to step away from what I’ve written for a day (or at least a night of sleep) before attempting to revise. It helps me approach clunky phrases and rough transitions with fresh eyes. If you don’t have that luxury, just get away from your computer for a few minutes — use the bathroom, do some jumping jacks, eat an apple — and then come back and read through your piece.

As you revise, make sure you …

- Get the facts right. An argument with false evidence falls apart pretty quickly, so check your facts to make yours rock solid.

- Don’t misrepresent the opposition or their evidence. If someone who holds the opposing view reads your essay, they should affirm how you explain their side — even if they disagree with your rebuttal.

- Present a case that builds over the course of your essay, makes sense, and ends on a strong note. One point should naturally lead to the next. Your readers shouldn’t feel like you’re constantly changing subjects. You’re making a variety of points, but your argument should feel like a cohesive whole.

- Paraphrase sources and cite them appropriately. Did you skip citations when writing your first draft? No worries — you can add them now. And check that you don’t overly rely on quotations. (Need help paraphrasing? Wordtune can help. Simply highlight the sentence or phrase you want to adjust and sort through Wordtune’s suggestions.)

- Tighten up overly wordy explanations and sharpen any convoluted ideas. Wordtune makes a great sidekick for this too 😉

Words to start an argumentative essay

The best way to introduce a convincing argument is to provide a strong thesis statement . These are the words I usually use to start an argumentative essay:

- It is indisputable that the world today is facing a multitude of issues

- With the rise of ____, the potential to make a positive difference has never been more accessible

- It is essential that we take action now and tackle these issues head-on

- it is critical to understand the underlying causes of the problems standing before us

- Opponents of this idea claim

- Those who are against these ideas may say

- Some people may disagree with this idea

- Some people may say that ____, however

When refuting an opposing concept, use:

- These researchers have a point in thinking

- To a certain extent they are right

- After seeing this evidence, there is no way one can agree with this idea

- This argument is irrelevant to the topic

Are you convinced by your own argument yet? Ready to brave the next get-together where everyone’s talking like they know something about intermittent fasting , chicken enclosures , or snow removal policies?

Now if someone asks you to explain your evidence-based but controversial opinion, you can hand them your essay and ask them to report back after they’ve read it.

Share This Article:

How to Master Concise Writing: 9 Tips to Write Clear and Crisp Content

Title Case vs. Sentence Case: How to Capitalize Your Titles

How to Properly Conduct Research with AI: Tools, Process, and Approach

Looking for fresh content, thank you your submission has been received.

- SAT BootCamp

- SAT MasterClass

- SAT Private Tutoring

- SAT Proctored Practice Test

- ACT Private Tutoring

- Academic Subjects

- College Essay Workshop

- Academic Writing Workshop

- AP English FRQ BootCamp

- 1:1 College Essay Help

- Online Instruction

- Free Resources

12 Essential Steps for Writing an Argumentative Essay (with 10 example essays)

Bonus Material: 10 complete example essays

Writing an essay can often feel like a Herculean task. How do you go from a prompt… to pages of beautifully-written and clearly-supported writing?

This 12-step method is for students who want to write a great essay that makes a clear argument.

In fact, using the strategies from this post, in just 88 minutes, one of our students revised her C+ draft to an A.

If you’re interested in learning how to write awesome argumentative essays and improve your writing grades, this post will teach you exactly how to do it.

First, grab our download so you can follow along with the complete examples.

Then keep reading to see all 12 essential steps to writing a great essay.

Download 10 example essays

Why you need to have a plan

One of the most common mistakes that students make when writing is to just dive in haphazardly without a plan.