Along with Stanford news and stories, show me:

- Student information

- Faculty/Staff information

We want to provide announcements, events, leadership messages and resources that are relevant to you. Your selection is stored in a browser cookie which you can remove at any time using “Clear all personalization” below.

Speaking, writing and reading are integral to everyday life, where language is the primary tool for expression and communication. Studying how people use language – what words and phrases they unconsciously choose and combine – can help us better understand ourselves and why we behave the way we do.

Linguistics scholars seek to determine what is unique and universal about the language we use, how it is acquired and the ways it changes over time. They consider language as a cultural, social and psychological phenomenon.

“Understanding why and how languages differ tells about the range of what is human,” said Dan Jurafsky , the Jackson Eli Reynolds Professor in Humanities and chair of the Department of Linguistics in the School of Humanities and Sciences at Stanford . “Discovering what’s universal about languages can help us understand the core of our humanity.”

The stories below represent some of the ways linguists have investigated many aspects of language, including its semantics and syntax, phonetics and phonology, and its social, psychological and computational aspects.

Understanding stereotypes

Stanford linguists and psychologists study how language is interpreted by people. Even the slightest differences in language use can correspond with biased beliefs of the speakers, according to research.

One study showed that a relatively harmless sentence, such as “girls are as good as boys at math,” can subtly perpetuate sexist stereotypes. Because of the statement’s grammatical structure, it implies that being good at math is more common or natural for boys than girls, the researchers said.

Language can play a big role in how we and others perceive the world, and linguists work to discover what words and phrases can influence us, unknowingly.

How well-meaning statements can spread stereotypes unintentionally

New Stanford research shows that sentences that frame one gender as the standard for the other can unintentionally perpetuate biases.

Algorithms reveal changes in stereotypes

New Stanford research shows that, over the past century, linguistic changes in gender and ethnic stereotypes correlated with major social movements and demographic changes in the U.S. Census data.

Exploring what an interruption is in conversation

Stanford doctoral candidate Katherine Hilton found that people perceive interruptions in conversation differently, and those perceptions differ depending on the listener’s own conversational style as well as gender.

Cops speak less respectfully to black community members

Professors Jennifer Eberhardt and Dan Jurafsky, along with other Stanford researchers, detected racial disparities in police officers’ speech after analyzing more than 100 hours of body camera footage from Oakland Police.

How other languages inform our own

People speak roughly 7,000 languages worldwide. Although there is a lot in common among languages, each one is unique, both in its structure and in the way it reflects the culture of the people who speak it.

Jurafsky said it’s important to study languages other than our own and how they develop over time because it can help scholars understand what lies at the foundation of humans’ unique way of communicating with one another.

“All this research can help us discover what it means to be human,” Jurafsky said.

Stanford PhD student documents indigenous language of Papua New Guinea

Fifth-year PhD student Kate Lindsey recently returned to the United States after a year of documenting an obscure language indigenous to the South Pacific nation.

Students explore Esperanto across Europe

In a research project spanning eight countries, two Stanford students search for Esperanto, a constructed language, against the backdrop of European populism.

Chris Manning: How computers are learning to understand language

A computer scientist discusses the evolution of computational linguistics and where it’s headed next.

Stanford research explores novel perspectives on the evolution of Spanish

Using digital tools and literature to explore the evolution of the Spanish language, Stanford researcher Cuauhtémoc García-García reveals a new historical perspective on linguistic changes in Latin America and Spain.

Language as a lens into behavior

Linguists analyze how certain speech patterns correspond to particular behaviors, including how language can impact people’s buying decisions or influence their social media use.

For example, in one research paper, a group of Stanford researchers examined the differences in how Republicans and Democrats express themselves online to better understand how a polarization of beliefs can occur on social media.

“We live in a very polarized time,” Jurafsky said. “Understanding what different groups of people say and why is the first step in determining how we can help bring people together.”

Analyzing the tweets of Republicans and Democrats

New research by Dora Demszky and colleagues examined how Republicans and Democrats express themselves online in an attempt to understand how polarization of beliefs occurs on social media.

Examining bilingual behavior of children at Texas preschool

A Stanford senior studied a group of bilingual children at a Spanish immersion preschool in Texas to understand how they distinguished between their two languages.

Predicting sales of online products from advertising language

Stanford linguist Dan Jurafsky and colleagues have found that products in Japan sell better if their advertising includes polite language and words that invoke cultural traditions or authority.

Language can help the elderly cope with the challenges of aging, says Stanford professor

By examining conversations of elderly Japanese women, linguist Yoshiko Matsumoto uncovers language techniques that help people move past traumatic events and regain a sense of normalcy.

The power of language: we translate our thoughts into words, but words also affect the way we think

Professor of Cognitive Neuroscience, Bangor University

Disclosure statement

Guillaume Thierry has received funding from the European Research Council, the Economic and Social Research Council, the British Academy, the Arts and Humanities Research Council, the Biotechnology and Biological Research Council, and the Arts Council of Wales.

Bangor University provides funding as a member of The Conversation UK.

View all partners

- Bahasa Indonesia

Have you ever worried in your student years or later in life that time may be starting to run out to achieve your goals? If so, would it be easier conveying this feeling to others if there was a word meaning just that? In German, there is. That feeling of panic associated with one’s opportunities appearing to run out is called Torschlusspanik .

German has a rich collection of such terms, made up of often two, three or more words connected to form a superword or compound word. Compound words are particularly powerful because they are (much) more than the sum of their parts. Torschlusspanik, for instance, is literally made of “gate”-“closing”-“panic”.

If you get to the train station a little late and see your train’s doors still open, you may have experienced a concrete form of Torschlusspanik, prompted by the characteristic beeps as the train doors are about to close. But this compound word of German is associated with more than the literal meaning. It evokes something more abstract, referring to the feeling that life is progressively shutting the door of opportunities as time goes by.

English too has many compound words. Some combine rather concrete words like “seahorse”, “butterfly”, or “turtleneck”. Others are more abstract, such as “backwards” or “whatsoever”. And of course in English too, compounds are superwords, as in German or French, since their meaning is often distinct from the meaning of its parts. A seahorse is not a horse, a butterfly is not a fly, turtles don’t wear turtlenecks, etc.

One remarkable feature of compound words is that they don’t translate well at all from one language to another, at least when it comes to translating their constituent parts literally. Who would have thought that a “carry-sheets” is a wallet – porte-feuille –, or that a “support-throat” is a bra – soutien-gorge – in French?

This begs the question of what happens when words don’t readily translate from one language to another. For instance, what happens when a native speaker of German tries to convey in English that they just had a spurt of Torschlusspanik? Naturally, they will resort to paraphrasing, that is, they will make up a narrative with examples to make their interlocutor understand what they are trying to say.

But then, this begs another, bigger question: Do people who have words that simply do not translate in another language have access to different concepts? Take the case of hiraeth for instance, a beautiful word of Welsh famous for being essentially untranslatable. Hiraeth is meant to convey the feeling associated with the bittersweet memory of missing something or someone, while being grateful of their existence.

Hiraeth is not nostalgia, it is not anguish, or frustration, or melancholy, or regret. And no, it is not homesickness, as Google translate may lead you to believe, since hiraeth also conveys the feeling one experiences when they ask someone to marry them and they are turned down, hardly a case of homesickness.

Different words, different minds?

The existence of a word in Welsh to convey this particular feeling poses a fundamental question on language–thought relationships. Asked in ancient Greece by philosophers such as Herodotus (450 BC), this question has resurfaced in the middle of the last century, under the impetus of Edward Sapir and his student Benjamin Lee Whorf , and has become known as the linguistic relativity hypothesis.

Linguistic relativity is the idea that language, which most people agree originates in and expresses human thought, can feedback to thinking, influencing thought in return. So, could different words or different grammatical constructs “shape” thinking differently in speakers of different languages? Being quite intuitive, this idea has enjoyed quite of bit of success in popular culture, lately appearing in a rather provocative form in the science fiction movie Arrival.

Although the idea is intuitive for some, exaggerated claims have been made about the extent of vocabulary diversity in some languages. Exaggerations have enticed illustrious linguists to write satirical essays such as “ the great Eskimo vocabulary hoax ”, where Geoff Pullum denounces the fantasy about the number of words used by Eskimos to refer to snow. However, whatever the actual number of words for snow in Eskimo, Pullum’s pamphlet fails to address an important question: what do we actually know about Eskimos’ perception of snow?

No matter how vitriolic critics of the linguistic relativity hypothesis may be, experimental research seeking scientific evidence for the existence of differences between speakers of different languages has started accumulating at a steady pace. For instance, Panos Athanasopoulos at Lancaster University, has made striking observations that having particular words to distinguish colour categories goes hand-in-hand with appreciating colour contrasts . So, he points out, native speakers of Greek, who have distinct basic colour terms for light and dark blue ( ghalazio and ble respectively) tend to consider corresponding shades of blue as more dissimilar than native speaker of English, who use the same basic term “blue” to describe them.

But scholars including Steven Pinker at Harvard are unimpressed, arguing that such effects are trivial and uninteresting, because individuals engaged in experiments are likely to use language in their head when making judgements about colours – so their behaviour is superficially influenced by language, while everyone sees the world in the same way.

To progress in this debate , I believe we need to get closer to the human brain, by measuring perception more directly, preferably within the small fraction of time preceding mental access to language. This is now possible, thanks to neuroscientific methods and – incredibly – early results lean in favour of Sapir and Whorf’s intuition.

So, yes, like it or not, it may well be that having different words means having differently structured minds. But then, given that every mind on earth is unique and distinct, this is not really a game changer.

- Linguistics

- Neurolinguistics

Case Management Specialist

Lecturer / Senior Lecturer - Marketing

Assistant Editor - 1 year cadetship

Executive Dean, Faculty of Health

Lecturer/Senior Lecturer, Earth System Science (School of Science)

A Summary and Analysis of George Orwell’s ‘Politics and the English Language’

By Dr Oliver Tearle (Loughborough University)

‘Politics and the English Language’ (1946) is one of the best-known essays by George Orwell (1903-50). As its title suggests, Orwell identifies a link between the (degraded) English language of his time and the degraded political situation: Orwell sees modern discourse (especially political discourse) as being less a matter of words chosen for their clear meanings than a series of stock phrases slung together.

You can read ‘Politics and the English Language’ here before proceeding to our summary and analysis of Orwell’s essay below.

‘Politics and the English Language’: summary

Orwell begins by drawing attention to the strong link between the language writers use and the quality of political thought in the current age (i.e. the 1940s). He argues that if we use language that is slovenly and decadent, it makes it easier for us to fall into bad habits of thought, because language and thought are so closely linked.

Orwell then gives five examples of what he considers bad political writing. He draws attention to two faults which all five passages share: staleness of imagery and lack of precision . Either the writers of these passages had a clear meaning to convey but couldn’t express it clearly, or they didn’t care whether they communicated any particular meaning at all, and were simply saying things for the sake of it.

Orwell writes that this is a common problem in current political writing: ‘prose consists less and less of words chosen for the sake of their meaning, and more and more of phrases tacked together like the sections of a prefabricated hen-house.’

Next, Orwell elaborates on the key faults of modern English prose, namely:

Dying Metaphors : these are figures of speech which writers lazily reach for, even though such phrases are worn-out and can no longer convey a vivid image. Orwell cites a number of examples, including toe the line , no axe to grind , Achilles’ heel , and swansong . Orwell’s objection to such dying metaphors is that writers use them without even thinking about what the phrases actually mean, such as when people misuse toe the line by writing it as tow the line , or when they mix their metaphors, again, because they’re not interested in what those images evoke.

Operators or Verbal False Limbs : this is when a longer and rather vague phrase is used in place of a single-word (and more direct) verb, e.g. make contact with someone, which essentially means ‘contact’ someone. The passive voice is also common, and writing phrases like by examination of instead of the more direct by examining . Sentences are saved from fizzling out (because the thought or idea being conveyed is not particularly striking) by largely meaningless closing platitudes such as greatly to be desired or brought to a satisfactory conclusion .

Pretentious Diction : Orwell draws attention to several areas here. He states that words like objective , basis , and eliminate are used by writers to dress up simple statements, making subjective opinion sound like scientific fact. Adjectives like epic , historic , and inevitable are used about international politics, while writing that glorifies war is full of old-fashioned words like realm , throne , and sword .

Foreign words and phrases like deus ex machina and mutatis mutandis are used to convey an air of culture and elegance. Indeed, many modern English writers are guilty of using Latin or Greek words in the belief that they are ‘grander’ than home-grown Anglo-Saxon ones: Orwell mentions Latinate words like expedite and ameliorate here. All of these examples are further proof of the ‘slovenliness and vagueness’ which Orwell detects in modern political prose.

Meaningless Words : Orwell argues that much art criticism and literary criticism in particular is full of words which don’t really mean anything at all, e.g. human , living , or romantic . ‘Fascism’, too, has lost all meaning in current political writing, effectively meaning ‘something not desirable’ (one wonders what Orwell would make of the word’s misuse in our current time!).

To prove his point, Orwell ‘translates’ a well-known passage from the Biblical Book of Ecclesiastes into modern English, with all its vagueness of language. ‘The whole tendency of modern prose’, he argues, ‘is away from concreteness.’ He draws attention to the concrete and everyday images (e.g. references to bread and riches) in the Bible passage, and the lack of any such images in his own fabricated rewriting of this passage.

The problem, Orwell says, is that it is too easy (and too tempting) to reach for these off-the-peg phrases than to be more direct or more original and precise in one’s speech or writing.

Orwell advises every writer to ask themselves four questions (at least): 1) what am I trying to say? 2) what words will express it? 3) what image or idiom will make it clearer? and 4) is this image fresh enough to have an effect? He proposes two further optional questions: could I put it more shortly? and have I said anything that is avoidably ugly?

Orthodoxy, Orwell goes on to observe, tends to encourage this ‘lifeless, imitative style’, whereas rebels who are not parroting the ‘party line’ will normally write in a more clear and direct style.

But Orwell also argues that such obfuscating language serves a purpose: much political writing is an attempt to defend the indefensible, such as the dropping of the atomic bomb on Japan (just one year before Orwell wrote ‘Politics and the English Language’), in such a euphemistic way that the ordinary reader will find it more palatable.

When your aim is to make such atrocities excusable, language which doesn’t evoke any clear mental image (e.g. of burning bodies in Hiroshima) is actually desirable.

Orwell argues that just as thought corrupts language, language can corrupt thought, with these ready-made phrases preventing writers from expressing anything meaningful or original. He believes that we should get rid of any word which has outworn its usefulness and should aim to use ‘the fewest and shortest words that will cover one’s meaning’.

Writers should let the meaning choose the word, rather than vice versa. We should think carefully about what we want to say until we have the right mental pictures to convey that thought in the clearest language.

Orwell concludes ‘Politics and the English Language’ with six rules for the writer to follow:

i) Never use a metaphor, simile or other figure of speech which you are used to seeing in print.

ii) Never use a long word where a short one will do.

iii) If it is possible to cut a word out, always cut it out.

iv) Never use the passive where you can use the active.

v) Never use a foreign phrase, a scientific word or a jargon word if you can think of an everyday English equivalent.

vi) Break any of these rules sooner than say anything outright barbarous.

‘Politics and the English Language’: analysis

In some respects, ‘Politics and the English Language’ advances an argument about good prose language which is close to what the modernist poet and thinker T. E. Hulme (1883-1917) argued for poetry in his ‘ A Lecture on Modern Poetry ’ and ‘Notes on Language and Style’ almost forty years earlier.

Although Hulme and Orwell came from opposite ends of the political spectrum, their objections to lazy and worn-out language stem are in many ways the same.

Hulme argued that poetry should be a forge where fresh metaphors are made: images which make us see the world in a slightly new way. But poetic language decays into common prose language before dying a lingering death in journalists’ English. The first time a poet described a hill as being ‘clad [i.e. clothed] with trees’, the reader would probably have mentally pictured such an image, but in time it loses its power to make us see anything.

Hulme calls these worn-out expressions ‘counters’, because they are like discs being moved around on a chessboard: an image which is itself not unlike Orwell’s prefabricated hen-house in ‘Politics and the English Language’.

Of course, Orwell’s focus is English prose rather than poetry, and his objections to sloppy writing are not principally literary (although that is undoubtedly a factor) but, above all, political. And he is keen to emphasise that his criticism of bad language, and suggestions for how to improve political writing, are both, to an extent, hopelessly idealistic: as he observes towards the end of ‘Politics and the English Language’, ‘Look back through this essay, and for certain you will find that I have again and again committed the very faults I am protesting against.’

But what Orwell advises is that the writer be on their guard against such phrases, the better to avoid them where possible. This is why he encourages writers to be more self-questioning (‘What am I trying to say? What words will express it? What image or idiom will make it clearer? Is this image fresh enough to have an effect?’) when writing political prose.

Nevertheless, the link between the standard of language and the kind of politics a particular country, regime, or historical era has is an important one. As Orwell writes: ‘I should expect to find – this is a guess which I have not sufficient knowledge to verify – that the German, Russian and Italian languages have all deteriorated in the last ten or fifteen years, as a result of dictatorship.’

Those writing under a dictatorship cannot write or speak freely, of course, but more importantly, those defending totalitarian rule must bend and abuse language in order to make ugly truths sound more attractive to the general populace, and perhaps to other nations.

In more recent times, the phrase ‘collateral damage’ is one of the more objectionable phrases used about war, hiding the often ugly reality (innocent civilians who are unfortunate victims of violence, but who are somehow viewed as a justifiable price to pay for the greater good).

Although Orwell’s essay has been criticised for being too idealistic, in many ways ‘Politics and the English Language’ remains as relevant now as it was in 1946 when it was first published.

Indeed, to return to Orwell’s opening point about decadence, it is unavoidable that the standard of political discourse has further declined since Orwell’s day. Perhaps it’s time a few more influential writers started heeding his argument?

Discover more from Interesting Literature

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.

Type your email…

9 thoughts on “A Summary and Analysis of George Orwell’s ‘Politics and the English Language’”

- Pingback: 10 of the Best Works by George Orwell – Interesting Literature

- Pingback: The Best George Orwell Essays Everyone Should Read – Interesting Literature

YES! Thank you!

A great and useful post. As a writer, I have been seriously offended by the politicization of the language in the past 50 years. Much of this is supposedly to sanitize, de-genderize, or diversity-fie language – exactly as it’s done in Orwell’s “1984.” How did a wonderfully useful word like gay – cheerful or lively – come to mean homosexual? And is optics not a branch of physics? Ironically, when the liberal but sensible JK Rowling criticized the replacement of “woman” with “person who menstruates” SHE was the one attacked. Now, God help us, we hope “crude” spaceships will get humans to Mars – which, if you research the poor quality control in Tesla cars, might in fact be a proper term.

And less anyone out there misread, this or me – I was a civil rights marcher, taught in a girls’ high school (where I got in minor trouble for suggesting to the students that they should aim higher than the traditional jobs of nurse or teacher), and – while somewhat of a mugwump – consider myself a liberal.

But I will fight to keep the language and the history from being 1984ed.

My desert island book would be the Everyman Essays of Orwell which is around 1200 pages. I’ve read it all the way through twice without fatigue and read individual essays endlessly. His warmth and affability help, Even better than Montaigne in this heretic’s view.

- Pingback: Q Marks the Spot 149 (March 2021 Treasure Map) – Quaerentia

I’ll go against the flow here and say Orwell was – at least in part – quite wrong here. If I recall correctly, he was wrong about a few things including, I think, the right way to make a cup of tea! In all seriousness, what he fails to acknowledge in this essay is that language is a living thing and belongs to the people, not the theorists, at all time. If a metaphor changes because of homophone mix up or whatever, then so be it. Many of our expressions we have little idea of now – I think of ‘baited breath’ which almost no one, even those who know how it should be spelt, realise should be ‘abated breath’.

Worse than this though, his ‘rules’ have indeed been taken up by many would-be writers to horrifying effect. I recall learning to make up new metaphors and similes rather than use clichés when I first began training ten years ago or more. I saw some ghastly new metaphors over time which swiftly made me realise that there’s a reason we use the same expressions a great deal and that is they are familiar and do the job well. To look at how to use them badly, just try reading Gregory David Roberts ‘Shantaram’. Similarly, the use of active voice has led to unpalatable writing which lacks character. The passive voice may well become longwinded when badly used, but it brings character when used well.

That said, Orwell is rarely completely wrong. Some of his points – essentially, use words you actually understand and don’t be pretentious – are valid. But the idea of the degradation of politics is really quite a bit of nonsense!

Always good to get some critique of Orwell, Ken! And I do wonder how tongue-in-cheek he was when proposing his guidelines – after all, even he admits he’s probably broken several of his own rules in the course of his essay! I think I’m more in the T. E. Hulme camp than the Orwell – poetry can afford to bend language in new ways (indeed, it often should do just this), and create daring new metaphors and ways of viewing the world. But prose, especially political non-fiction, is there to communicate an argument or position, and I agree that ghastly new metaphors would just get in the way. One of the things that is refreshing reading Orwell is how many of the problems he identified are still being discussed today, often as if they are new problems that didn’t exist a few decades ago. Orwell shows that at least one person was already discussing them over half a century ago!

Absolutely true! When you have someone of Orwell’s intelligence and clear thinking, even when you believe him wrong or misguided, he is still relevant and remains so decades later.

Comments are closed.

Subscribe now to keep reading and get access to the full archive.

Continue reading

- Share full article

Advertisement

Supported by

How the English Language Conquered the World

By Amy Chua

- Jan. 18, 2022

THE RISE OF ENGLISH Global Politics and the Power of Language By Rosemary Salomone

“Every time the question of language surfaces,” the Italian Marxist philosopher Antonio Gramsci wrote, “in one way or another a series of other problems are coming to the fore,” like “the enlargement of the governing class,” the “relationships between the governing groups and the national–popular mass” and the fight over “cultural hegemony.” Vindicating Gramsci, Rosemary Salomone’s “The Rise of English” explores the language wars being fought all over the world, revealing the political, economic and cultural stakes behind these wars, and showing that so far English is winning. It is a panoramic, endlessly fascinating and eye-opening book, with an arresting fact on nearly every page.

English is the world’s most widely spoken language, with some 1.5 billion speakers even though it’s native for fewer than 400 million. English accounts for 60 percent of world internet content and is the lingua franca of pop culture and the global economy. All 100 of the world’s most influential science journals publish in English. “Across Europe, close to 100 percent of students study English at some point in their education.”

Even in France, where countering the hegemony of English is an official obsession, English is winning. French bureaucrats constantly try to ban Anglicisms “such as gamer , dark web and fake news ,” Salomone writes, but their edicts are “quietly ignored.” Although a French statute called the Toubon Law “requires radio stations to play 35 percent French songs,” “the remaining 65 percent is flooded with American music.” Many young French artists sing in English. By law, French schoolchildren must study a foreign language, and while eight languages are available, 90 percent choose English.

Salomone, the Kenneth Wang professor of law at St. John’s University School of Law, tends to glide over why English won, simply stating that English is the language of neoliberalism and globalization, which seems to beg the question. But she is meticulous and nuanced in chronicling the battles being fought over language policy in countries ranging from Italy to Congo, and analyzing the unexpected winners and losers.

Exactly whom English benefits is complicated. Obviously it benefits native Anglophones. Americans, with what Salomone calls their “smug monolingualism,” are often blissfully unaware of the advantage they have because of the worldwide dominance of their native tongue. English also benefits globally connected market-dominant minorities in non-Western countries, like English-speaking whites in South Africa or the Anglophone Tutsi elite in Rwanda. In former French colonies like Algeria and Morocco, shifting from French to English is seen not just as the key to modernization, but as a form of resistance against their colonial past.

In India, the role of English is spectacularly complex. The ruling Hindu nationalist Indian People’s Party prefers to depict English as the colonizers’ language, impeding the vision of an India unified by Hindu culture and Hindi. By contrast, for speakers of non-Hindi languages and members of lower castes, English is often seen as a shield against majority domination. Some reformers see English as an “egalitarian language” in contrast to Indian languages, which carry “the legacy of caste.” English is also a symbol of social status. As a character in a recent Bollywood hit says: “English isn’t just a language in this country. It’s a class.” Meanwhile, Indian tiger parents, “from the wealthiest to the poorest,” press for their children to be taught in English, seeing it as the ticket to upward mobility.

Salomone’s South Africa chapter is among the most interesting in the book. Along with Afrikaans, English is one of South Africa’s 11 official languages, and even though only 9.6 percent of the population speak English as their first language, it “dominates every sector,” including government, the internet, business, broadcasting, the press, street signs and popular music. But English is not only the language of South Africa’s commercial and political elite. It was also the language of Black resistance to the Afrikaner-dominated apartheid regime, giving it enormous symbolic importance. Thus, recent years have seen poor and working-class Black activists pushing for English-only instruction in universities, even though many of them are not proficient in the language. Opponents of English, however, argue that shifting away from Afrikaans instruction disproportionately hurts the poor of all races, including lower-income Blacks, whites and mixed-race “colored” South Africans. Meanwhile, younger “colored activists are challenging the English-Afrikaans binary and exploring alternate forms of expression, like AfriKaaps,” a form of Afrikaans promoted by hip-hop artists. For now, though, “the constitutional commitment to language equality in South Africa is aspirational at best,” and “English reigns supreme for its economic power.”

Learning English pays, with “positive labor market returns across the globe.” Throughout academia today, even in Europe and Asia, “the rule no longer is ‘Publish or perish’ but rather ‘Publish in English … or perish.’” In the Middle East, “employees who were more proficient in English earned salaries from 5 percent (Tunisia) to a stunning 200 percent (Iraq) more than their non-English-speaking counterparts.” In Argentina, 90 percent of employers “believed that English was an indispensable skill for managers and directors.” In every country she surveys, higher income is correlated with English proficiency.

Salomone concludes with a brief discussion of American monolingualism, describing the waves of political angst over threats to English as the national language, while advocating for more multilingualism in Anglophone countries. Beyond the economic benefits of speaking multiple languages in a globalized world, Salomone cites studies that show learning new languages improves overall cognitive function. In addition, she argues, “observing life through a wide linguistic and cultural lens leads to greater creativity and innovation.”

“The Rise of English” has its weaknesses. Most important, the book lacks any clear thesis beyond suggesting “language is political; it’s complicated.” In addition, the book doesn’t tie together or reflect on the divergence of its case studies; I frequently found myself wondering why the experiences of (say) France or Italy or Denmark were different, and what we should take from that fact.

Finally, the book offers no clear evaluative framework. Salomone focuses primarily on straightforward economic factors (which often boil down to the same thing: access to global markets), but there is a smattering of underdeveloped discussion of other, more elusive themes too, like race, equity, colonialism and imperialism. This hodgepodge of incommensurables may trace back to the book’s origins. In her preface, Salomone writes, “My initial plan was to write a book on the value of language in the global economy.” But “the deeper I dug … the more I viewed the issues through a wider global lens and the clearer the connections to educational equity, identity and democratic participation appeared.” Unfortunately, she never quite gets a handle on these deeper issues.

Will Mandarin, with its 1.11 billion speakers, eventually replace English as the world’s lingua franca? Will Google or Microsoft Translate moot the issue? Salomone’s painstakingly thorough book addresses these questions too (concluding probably not).

The justifications for English — or any language — as a global lingua franca are based primarily in economic efficiency. By contrast, the reasons to protect local languages mostly sound in different registers — the importance of cultural heritage; the geopolitics of resistance to great powers; the value of Indigenous art; the beauty of idiosyncratic words in other languages that describe all the different types of snow or the different flavors of melancholia. As Gramsci reminded us, the question of who speaks what language invariably puts all this on the table.

Amy Chua is the John M. Duff Jr. professor of law at Yale Law School and the author of “World on Fire: How Exporting Free Market Democracy Breeds Ethnic Hatred and Global Instability” and “Political Tribes: Group Instinct and the Fate of Nations.”

THE RISE OF ENGLISH Global Politics and the Power of Language By Rosemary Salomone 488 pp. Oxford University Press. $35.

- Tools and Resources

- Customer Services

- Communication and Culture

- Communication and Social Change

- Communication and Technology

- Communication Theory

- Critical/Cultural Studies

- Gender (Gay, Lesbian, Bisexual and Transgender Studies)

- Health and Risk Communication

- Intergroup Communication

- International/Global Communication

- Interpersonal Communication

- Journalism Studies

- Language and Social Interaction

- Mass Communication

- Media and Communication Policy

- Organizational Communication

- Political Communication

- Rhetorical Theory

- Share This Facebook LinkedIn Twitter

Article contents

Language and power.

- Sik Hung Ng Sik Hung Ng Department of Psychology, Renmin University of China

- and Fei Deng Fei Deng School of Foreign Studies, South China Agricultural University

- https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780190228613.013.436

- Published online: 22 August 2017

Five dynamic language–power relationships in communication have emerged from critical language studies, sociolinguistics, conversation analysis, and the social psychology of language and communication. Two of them stem from preexisting powers behind language that it reveals and reflects, thereby transferring the extralinguistic powers to the communication context. Such powers exist at both the micro and macro levels. At the micro level, the power behind language is a speaker’s possession of a weapon, money, high social status, or other attractive personal qualities—by revealing them in convincing language, the speaker influences the hearer. At the macro level, the power behind language is the collective power (ethnolinguistic vitality) of the communities that speak the language. The dominance of English as a global language and international lingua franca, for example, has less to do with its linguistic quality and more to do with the ethnolinguistic vitality of English-speakers worldwide that it reflects. The other three language–power relationships refer to the powers of language that are based on a language’s communicative versatility and its broad range of cognitive, communicative, social, and identity functions in meaning-making, social interaction, and language policies. Such language powers include, first, the power of language to maintain existing dominance in legal, sexist, racist, and ageist discourses that favor particular groups of language users over others. Another language power is its immense impact on national unity and discord. The third language power is its ability to create influence through single words (e.g., metaphors), oratories, conversations and narratives in political campaigns, emergence of leaders, terrorist narratives, and so forth.

- power behind language

- power of language

- intergroup communication

- World Englishes

- oratorical power

- conversational power

- leader emergence

- al-Qaeda narrative

- social identity approach

Introduction

Language is for communication and power.

Language is a natural human system of conventionalized symbols that have understood meanings. Through it humans express and communicate their private thoughts and feelings as well as enact various social functions. The social functions include co-constructing social reality between and among individuals, performing and coordinating social actions such as conversing, arguing, cheating, and telling people what they should or should not do. Language is also a public marker of ethnolinguistic, national, or religious identity, so strong that people are willing to go to war for its defense, just as they would defend other markers of social identity, such as their national flag. These cognitive, communicative, social, and identity functions make language a fundamental medium of human communication. Language is also a versatile communication medium, often and widely used in tandem with music, pictures, and actions to amplify its power. Silence, too, adds to the force of speech when it is used strategically to speak louder than words. The wide range of language functions and its versatility combine to make language powerful. Even so, this is only one part of what is in fact a dynamic relationship between language and power. The other part is that there is preexisting power behind language which it reveals and reflects, thereby transferring extralinguistic power to the communication context. It is thus important to delineate the language–power relationships and their implications for human communication.

This chapter provides a systematic account of the dynamic interrelationships between language and power, not comprehensively for lack of space, but sufficiently focused so as to align with the intergroup communication theme of the present volume. The term “intergroup communication” will be used herein to refer to an intergroup perspective on communication, which stresses intergroup processes underlying communication and is not restricted to any particular form of intergroup communication such as interethnic or intergender communication, important though they are. It echoes the pioneering attempts to develop an intergroup perspective on the social psychology of language and communication behavior made by pioneers drawn from communication, social psychology, and cognate fields (see Harwood et al., 2005 ). This intergroup perspective has fostered the development of intergroup communication as a discipline distinct from and complementing the discipline of interpersonal communication. One of its insights is that apparently interpersonal communication is in fact dynamically intergroup (Dragojevic & Giles, 2014 ). For this and other reasons, an intergroup perspective on language and communication behavior has proved surprisingly useful in revealing intergroup processes in health communication (Jones & Watson, 2012 ), media communication (Harwood & Roy, 2005 ), and communication in a variety of organizational contexts (Giles, 2012 ).

The major theoretical foundation that has underpinned the intergroup perspective is social identity theory (Tajfel, 1982 ), which continues to service the field as a metatheory (Abrams & Hogg, 2004 ) alongside relatively more specialized theories such as ethnolinguistic identity theory (Harwood et al., 1994 ), communication accommodation theory (Palomares et al., 2016 ), and self-categorization theory applied to intergroup communication (Reid et al., 2005 ). Against this backdrop, this chapter will be less concerned with any particular social category of intergroup communication or variant of social identity theory, and more with developing a conceptual framework of looking at the language–power relationships and their implications for understanding intergroup communication. Readers interested in an intra- or interpersonal perspective may refer to the volume edited by Holtgraves ( 2014a ).

Conceptual Approaches to Power

Bertrand Russell, logician cum philosopher and social activist, published a relatively little-known book on power when World War II was looming large in Europe (Russell, 2004 ). In it he asserted the fundamental importance of the concept of power in the social sciences and likened its importance to the concept of energy in the physical sciences. But unlike physical energy, which can be defined in a formula (e.g., E=MC 2 ), social power has defied any such definition. This state of affairs is not unexpected because the very nature of (social) power is elusive. Foucault ( 1979 , p. 92) has put it this way: “Power is everywhere, not because it embraces everything, but because it comes from everywhere.” This view is not beyond criticism but it does highlight the elusiveness of power. Power is also a value-laden concept meaning different things to different people. To functional theorists and power-wielders, power is “power to,” a responsibility to unite people and do good for all. To conflict theorists and those who are dominated, power is “power over,” which corrupts and is a source of social conflict rather than integration (Lenski, 1966 ; Sassenberg et al., 2014 ). These entrenched views surface in management–labor negotiations and political debates between government and opposition. Management and government would try to frame the negotiation in terms of “power to,” whereas labor and opposition would try to frame the same in “power over” in a clash of power discourses. The two discourses also interchange when the same speakers reverse their power relations: While in opposition, politicians adhere to “power over” rhetorics, once in government, they talk “power to.” And vice versa.

The elusive and value-laden nature of power has led to a plurality of theoretical and conceptual approaches. Five approaches that are particularly pertinent to the language–power relationships will be discussed, and briefly so because of space limitation. One approach views power in terms of structural dominance in society by groups who own and/or control the economy, the government, and other social institutions. Another approach views power as the production of intended effects by overcoming resistance that arises from objective conflict of interests or from psychological reactance to being coerced, manipulated, or unfairly treated. A complementary approach, represented by Kurt Lewin’s field theory, takes the view that power is not the actual production of effects but the potential for doing this. It looks behind power to find out the sources or bases of this potential, which may stem from the power-wielders’ access to the means of punishment, reward, and information, as well as from their perceived expertise and legitimacy (Raven, 2008 ). A fourth approach views power in terms of the balance of control/dependence in the ongoing social exchange between two actors that takes place either in the absence or presence of third parties. It provides a structural account of power-balancing mechanisms in social networking (Emerson, 1962 ), and forms the basis for combining with symbolic interaction theory, which brings in subjective factors such as shared social cognition and affects for the analysis of power in interpersonal and intergroup negotiation (Stolte, 1987 ). The fifth, social identity approach digs behind the social exchange account, which has started from control/dependence as a given but has left it unexplained, to propose a three-process model of power emergence (Turner, 2005 ). According to this model, it is psychological group formation and associated group-based social identity that produce influence; influence then cumulates to form the basis of power, which in turn leads to the control of resources.

Common to the five approaches above is the recognition that power is dynamic in its usage and can transform from one form of power to another. Lukes ( 2005 ) has attempted to articulate three different forms or faces of power called “dimensions.” The first, behavioral dimension of power refers to decision-making power that is manifest in the open contest for dominance in situations of objective conflict of interests. Non-decision-making power, the second dimension, is power behind the scene. It involves the mobilization of organizational bias (e.g., agenda fixing) to keep conflict of interests from surfacing to become public issues and to deprive oppositions of a communication platform to raise their voices, thereby limiting the scope of decision-making to only “safe” issues that would not challenge the interests of the power-wielder. The third dimension is ideological and works by socializing people’s needs and values so that they want the wants and do the things wanted by the power-wielders, willingly as their own. Conflict of interests, opposition, and resistance would be absent from this form of power, not because they have been maneuvered out of the contest as in the case of non-decision-making power, but because the people who are subject to power are no longer aware of any conflict of interest in the power relationship, which may otherwise ferment opposition and resistance. Power in this form can be exercised without the application of coercion or reward, and without arousing perceived manipulation or conflict of interests.

Language–Power Relationships

As indicated in the chapter title, discussion will focus on the language–power relationships, and not on language alone or power alone, in intergroup communication. It draws from all the five approaches to power and can be grouped for discussion under the power behind language and the power of language. In the former, language is viewed as having no power of its own and yet can produce influence and control by revealing the power behind the speaker. Language also reflects the collective/historical power of the language community that uses it. In the case of modern English, its preeminent status as a global language and international lingua franca has shaped the communication between native and nonnative English speakers because of the power of the English-speaking world that it reflects, rather than because of its linguistic superiority. In both cases, language provides a widely used conventional means to transfer extralinguistic power to the communication context. Research on the power of language takes the view that language has power of its own. This power allows a language to maintain the power behind it, unite or divide a nation, and create influence.

In Figure 1 we have grouped the five language–power relationships into five boxes. Note that the boundary between any two boxes is not meant to be rigid but permeable. For example, by revealing the power behind a message (box 1), a message can create influence (box 5). As another example, language does not passively reflect the power of the language community that uses it (box 2), but also, through its spread to other language communities, generates power to maintain its preeminence among languages (box 3). This expansive process of language power can be seen in the rise of English to global language status. A similar expansive process also applies to a particular language style that first reflects the power of the language subcommunity who uses the style, and then, through its common acceptance and usage by other subcommunities in the country, maintains the power of the subcommunity concerned. A prime example of this type of expansive process is linguistic sexism, which reflects preexisting male dominance in society and then, through its common usage by both sexes, contributes to the maintenance of male dominance. Other examples are linguistic racism and the language style of the legal profession, each of which, like linguistic sexism and the preeminence of the English language worldwide, has considerable impact on individuals and society at large.

Space precludes a full discussion of all five language–power relationships. Instead, some of them will warrant only a brief mention, whereas others will be presented in greater detail. The complexity of the language–power relations and their cross-disciplinary ramifications will be evident in the multiple sets of interrelated literatures that we cite from. These include the social psychology of language and communication, critical language studies (Fairclough, 1989 ), sociolinguistics (Kachru, 1992 ), and conversation analysis (Sacks et al., 1974 ).

Figure 1. Power behind language and power of language.

Power Behind Language

Language reveals power.

When negotiating with police, a gang may issue the threatening message, “Meet our demands, or we will shoot the hostages!” The threatening message may succeed in coercing the police to submit; its power, however, is more apparent than real because it is based on the guns gangsters posses. The message merely reveals the power of a weapon in their possession. Apart from revealing power, the gangsters may also cheat. As long as the message comes across as credible and convincing enough to arouse overwhelming fear, it would allow them to get away with their demands without actually possessing any weapon. In this case, language is used to produce an intended effect despite resistance by deceptively revealing a nonexisting power base and planting it in the mind of the message recipient. The literature on linguistic deception illustrates the widespread deceptive use of language-reveals-power to produce intended effects despite resistance (Robinson, 1996 ).

Language Reflects Power

Ethnolinguistic vitality.

The language that a person uses reflects the language community’s power. A useful way to think about a language community’s linguistic power is through the ethnolinguistic vitality model (Bourhis et al., 1981 ; Harwood et al., 1994 ). Language communities in a country vary in absolute size overall and, just as important, a relative numeric concentration in particular regions. Francophone Canadians, though fewer than Anglophone Canadians overall, are concentrated in Quebec to give them the power of numbers there. Similarly, ethnic minorities in mainland China have considerable power of numbers in those autonomous regions where they are concentrated, such as Inner Mongolia, Tibet, and Xinjiang. Collectively, these factors form the demographic base of the language community’s ethnolinguistic vitality, an index of the community’s relative linguistic dominance. Another base of ethnolinguistic vitality is institutional representations of the language community in government, legislatures, education, religion, the media, and so forth, which afford its members institutional leadership, influence, and control. Such institutional representation is often reinforced by a language policy that installs the language as the nation’s sole official language. The third base of ethnolinguistic vitality comprises sociohistorical and cultural status of the language community inside the nation and internationally. In short, the dominant language of a nation is one that comes from and reflects the high ethnolinguistic vitality of its language community.

An important finding of ethnolinguistic vitality research is that it is perceived vitality, and not so much its objective demographic-institutional-cultural strengths, that influences language behavior in interpersonal and intergroup contexts. Interestingly, the visibility and salience of languages shown on public and commercial signs, referred to as the “linguistic landscape,” serve important informational and symbolic functions as a marker of their relative vitality, which in turn affects the use of in-group language in institutional settings (Cenoz & Gorter, 2006 ; Landry & Bourhis, 1997 ).

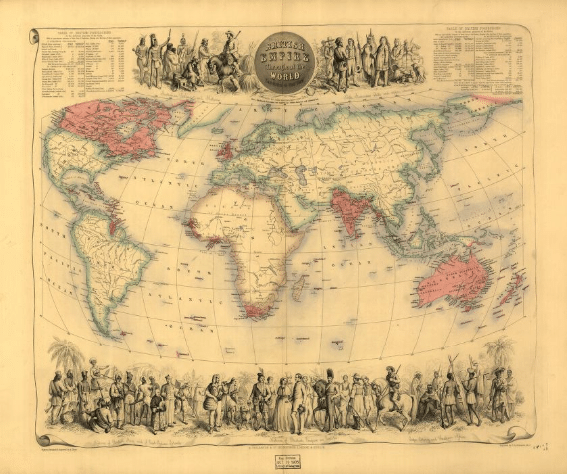

World Englishes and Lingua Franca English

Another field of research on the power behind and reflected in language is “World Englishes.” At the height of the British Empire English spread on the back of the Industrial Revolution and through large-scale migrations of Britons to the “New World,” which has since become the core of an “inner circle” of traditional native English-speaking nations now led by the United States (Kachru, 1992 ). The emergent wealth and power of these nations has maintained English despite the decline of the British Empire after World War II. In the post-War era, English has become internationalized with the support of an “outer circle” nations and, later, through its spread to “expanding circle” nations. Outer circle nations are made up mostly of former British colonies such as India, Pakistan, and Nigeria. In compliance with colonial language policies that institutionalized English as the new colonial national language, a sizeable proportion of the colonial populations has learned and continued using English over generations, thereby vastly increasing the number of English speakers over and above those in the inner circle nations. The expanding circle encompasses nations where English has played no historical government roles, but which are keen to appropriate English as the preeminent foreign language for local purposes such as national development, internationalization of higher education, and participation in globalization (e.g., China, Indonesia, South Korea, Japan, Egypt, Israel, and continental Europe).

English is becoming a global language with official or special status in at least 75 countries (British Council, n.d. ). It is also the language choice in international organizations and companies, as well as academia, and is commonly used in trade, international mass media, and entertainment, and over the Internet as the main source of information. English native speakers can now follow the worldwide English language track to find jobs overseas without having to learn the local language and may instead enjoy a competitive language advantage where the job requires English proficiency. This situation is a far cry from the colonial era when similar advantages had to come under political patronage. Alongside English native speakers who work overseas benefitting from the preeminence of English over other languages, a new phenomenon of outsourcing international call centers away from the United Kingdom and the United States has emerged (Friginal, 2007 ). Callers can find the information or help they need from people stationed in remote places such as India or the Philippines where English has penetrated.

As English spreads worldwide, it has also become the major international lingua franca, serving some 800 million multilinguals in Asia alone, and numerous others elsewhere (Bolton, 2008 ). The practical importance of this phenomenon and its impact on English vocabulary, grammar, and accent have led to the emergence of a new field of research called “English as a lingua franca” (Brosch, 2015 ). The twin developments of World Englishes and lingua franca English raise interesting and important research questions. A vast area of research lies in waiting.

Several lines of research suggest themselves from an intergroup communication perspective. How communicatively effective are English native speakers who are international civil servants in organizations such as the UN and WTO, where they habitually speak as if they were addressing their fellow natives without accommodating to the international audience? Another line of research is lingua franca English communication between two English nonnative speakers. Their common use of English signals a joint willingness of linguistic accommodation, motivated more by communication efficiency of getting messages across and less by concerns of their respective ethnolinguistic identities. An intergroup communication perspective, however, would sensitize researchers to social identity processes and nonaccommodation behaviors underneath lingua franca communication. For example, two nationals from two different countries, X and Y, communicating with each other in English are accommodating on the language level; at the same time they may, according to communication accommodation theory, use their respective X English and Y English for asserting their ethnolinguistic distinctiveness whilst maintaining a surface appearance of accommodation. There are other possibilities. According to a survey of attitudes toward English accents, attachment to “standard” native speaker models remains strong among nonnative English speakers in many countries (Jenkins, 2009 ). This suggests that our hypothetical X and Y may, in addition to asserting their respective Englishes, try to outperform one another in speaking with overcorrect standard English accents, not so much because they want to assert their respective ethnolinguistic identities, but because they want to project a common in-group identity for positive social comparison—“We are all English-speakers but I am a better one than you!”

Many countries in the expanding circle nations are keen to appropriate English for local purposes, encouraging their students and especially their educational elites to learn English as a foreign language. A prime example is the Learn-English Movement in China. It has affected generations of students and teachers over the past 30 years and consumed a vast amount of resources. The results are mixed. Even more disturbing, discontents and backlashes have emerged from anti-English Chinese motivated to protect the vitality and cultural values of the Chinese language (Sun et al., 2016 ). The power behind and reflected in modern English has widespread and far-reaching consequences in need of more systematic research.

Power of Language

Language maintains existing dominance.

Language maintains and reproduces existing dominance in three different ways represented respectively by the ascent of English, linguistic sexism, and legal language style. For reasons already noted, English has become a global language, an international lingua franca, and an indispensable medium for nonnative English speaking countries to participate in the globalized world. Phillipson ( 2009 ) referred to this phenomenon as “linguistic imperialism.” It is ironic that as the spread of English has increased the extent of multilingualism of non-English-speaking nations, English native speakers in the inner circle of nations have largely remained English-only. This puts pressure on the rest of the world to accommodate them in English, the widespread use of which maintains its preeminence among languages.

A language evolves and changes to adapt to socially accepted word meanings, grammatical rules, accents, and other manners of speaking. What is acceptable or unacceptable reflects common usage and hence the numerical influence of users, but also the elites’ particular language preferences and communication styles. Research on linguistic sexism has shown, for example, a man-made language such as English (there are many others) is imbued with sexist words and grammatical rules that reflect historical male dominance in society. Its uncritical usage routinely by both sexes in daily life has in turn naturalized male dominance and associated sexist inequalities (Spender, 1998 ). Similar other examples are racist (Reisigl & Wodak, 2005 ) and ageist (Ryan et al., 1995 ) language styles.

Professional languages are made by and for particular professions such as the legal profession (Danet, 1980 ; Mertz et al., 2016 ; O’Barr, 1982 ). The legal language is used not only among members of the profession, but also with the general public, who may know each and every word in a legal document but are still unable to decipher its meaning. Through its language, the legal profession maintains its professional dominance with the complicity of the general public, who submits to the use of the language and accedes to the profession’s authority in interpreting its meanings in matters relating to their legal rights and obligations. Communication between lawyers and their “clients” is not only problematic, but the public’s continual dependence on the legal language contributes to the maintenance of the dominance of the profession.

Language Unites and Divides a Nation

A nation of many peoples who, despite their diverse cultural and ethnic background, all speak in the same tongue and write in the same script would reap the benefit of the unifying power of a common language. The power of the language to unite peoples would be stronger if it has become part of their common national identity and contributed to its vitality and psychological distinctiveness. Such power has often been seized upon by national leaders and intellectuals to unify their countries and serve other nationalistic purposes (Patten, 2006 ). In China, for example, Emperor Qin Shi Huang standardized the Chinese script ( hanzi ) as an important part of the reforms to unify the country after he had defeated the other states and brought the Warring States Period ( 475–221 bc ) to an end. A similar reform of language standardization was set in motion soon after the overthrow of the Qing Dynasty ( ad 1644–1911 ), by simplifying some of the hanzi and promoting Putonghua as the national standard oral language. In the postcolonial part of the world, language is often used to service nationalism by restoring the official status of their indigenous language as the national language whilst retaining the colonial language or, in more radical cases of decolonization, relegating the latter to nonofficial status. Yet language is a two-edged sword: It can also divide a nation. The tension can be seen in competing claims to official-language status made by minority language communities, protest over maintenance of minority languages, language rights at schools and in courts of law, bilingual education, and outright language wars (Calvet, 1998 ; DeVotta, 2004 ).

Language Creates Influence

In this section we discuss the power of language to create influence through single words and more complex linguistic structures ranging from oratories and conversations to narratives/stories.

Power of Single Words

Learning a language empowers humans to master an elaborate system of conventions and the associations between words and their sounds on the one hand, and on the other hand, categories of objects and relations to which they refer. After mastering the referential meanings of words, a person can mentally access the objects and relations simply by hearing or reading the words. Apart from their referential meanings, words also have connotative meanings with their own social-cognitive consequences. Together, these social-cognitive functions underpin the power of single words that has been extensively studied in metaphors, which is a huge research area that crosses disciplinary boundaries and probes into the inner workings of the brain (Benedek et al., 2014 ; Landau et al., 2014 ; Marshal et al., 2007 ). The power of single words extends beyond metaphors. It can be seen in misleading words in leading questions (Loftus, 1975 ), concessive connectives that reverse expectations from real-world knowledge (Xiang & Kuperberg, 2014 ), verbs that attribute implicit causality to either verb subject or object (Hartshorne & Snedeker, 2013 ), “uncertainty terms” that hedge potentially face-threatening messages (Holtgraves, 2014b ), and abstract words that signal power (Wakslak et al., 2014 ).

The literature on the power of single words has rarely been applied to intergroup communication, with the exception of research arising from the linguistic category model (e.g., Semin & Fiedler, 1991 ). The model distinguishes among descriptive action verbs (e.g., “hits”), interpretative action verbs (e.g., “hurts”) and state verbs (e.g., “hates”), which increase in abstraction in that order. Sentences made up of abstract verbs convey more information about the protagonist, imply greater temporal and cross-situational stability, and are more difficult to disconfirm. The use of abstract language to represent a particular behavior will attribute the behavior to the protagonist rather than the situation and the resulting image of the protagonist will persist despite disconfirming information, whereas the use of concrete language will attribute the same behavior more to the situation and the resulting image of the protagonist will be easier to change. According to the linguistic intergroup bias model (Maass, 1999 ), abstract language will be used to represent positive in-group and negative out-group behaviors, whereas concrete language will be used to represent negative in-group and positive out-group behaviors. The combined effects of the differential use of abstract and concrete language would, first, lead to biased attribution (explanation) of behavior privileging the in-group over the out-group, and second, perpetuate the prejudiced intergroup stereotypes. More recent research has shown that linguistic intergroup bias varies with the power differential between groups—it is stronger in high and low power groups than in equal power groups (Rubini et al., 2007 ).

Oratorical Power

A charismatic speaker may, by the sheer force of oratory, buoy up people’s hopes, convert their hearts from hatred to forgiveness, or embolden them to take up arms for a cause. One may recall moving speeches (in English) such as Susan B. Anthony’s “On Women’s Right to Vote,” Winston Churchill’s “We Shall Fight on the Beaches,” Mahatma Gandhi’s “Quit India,” or Martin Luther King, Jr.’s “I Have a Dream.” The speech may be delivered face-to-face to an audience, or broadcast over the media. The discussion below focuses on face-to-face oratories in political meetings.

Oratorical power may be measured in terms of money donated or pledged to the speaker’s cause, or, in a religious sermon, the number of converts made. Not much research has been reported on these topics. Another measurement approach is to count the frequency of online audience responses that a speech has generated, usually but not exclusively in the form of applause. Audience applause can be measured fairly objectively in terms of frequency, length, or loudness, and collected nonobtrusively from a public recording of the meeting. Audience applause affords researchers the opportunity to explore communicative and social psychological processes that underpin some aspects of the power of rhetorical formats. Note, however, that not all incidences of audience applause are valid measures of the power of rhetoric. A valid incidence should be one that is invited by the speaker and synchronized with the flow of the speech, occurring at the appropriate time and place as indicated by the rhetorical format. Thus, an uninvited incidence of applause would not count, nor is one that is invited but has occurred “out of place” (too soon or too late). Furthermore, not all valid incidences are theoretically informative to the same degree. An isolated applause from just a handful of the audience, though valid and in the right place, has relatively little theoretical import for understanding the power of rhetoric compared to one that is made by many acting in unison as a group. When the latter occurs, it would be a clear indication of the power of rhetorically formulated speech. Such positive audience response constitutes the most direct and immediate means by which an audience can display its collective support for the speaker, something which they would not otherwise show to a speech of less power. To influence and orchestrate hundreds and thousands of people in the audience to precisely coordinate their response to applaud (and cheer) together as a group at the right time and place is no mean feat. Such a feat also influences the wider society through broadcast on television and other news and social media. The combined effect could be enormous there and then, and its downstream influence far-reaching, crossing country boarders and inspiring generations to come.

To accomplish the feat, an orator has to excite the audience to applaud, build up the excitement to a crescendo, and simultaneously cue the audience to synchronize their outburst of stored-up applause with the ongoing speech. Rhetorical formats that aid the orator to accomplish the dual functions include contrast, list, puzzle solution, headline-punchline, position-taking, and pursuit (Heritage & Greatbatch, 1986 ). To illustrate, we cite the contrast and list formats.

A contrast, or antithesis, is made up of binary schemata such as “too much” and “too little.” Heritage and Greatbatch ( 1986 , p. 123) reported the following example:

Governments will argue that resources are not available to help disabled people. The fact is that too much is spent on the munitions of war, and too little is spent on the munitions of peace [italics added]. As the audience is familiar with the binary schema of “too much” and “too little” they can habitually match the second half of the contrast against the first half. This decoding process reinforces message comprehension and helps them to correctly anticipate and applaud at the completion point of the contrast. In the example quoted above, the speaker micropaused for 0.2 seconds after the second word “spent,” at which point the audience began to applaud in anticipation of the completion point of the contrast, and applauded more excitedly upon hearing “. . . on the munitions of peace.” The applause continued and lasted for 9.2 long seconds.

A list is usually made up of a series of three parallel words, phrases or clauses. “Government of the people, by the people, for the people” is a fine example, as is Obama’s “It’s been a long time coming, but tonight, because of what we did on this day , in this election , at this defining moment , change has come to America!” (italics added) The three parts in the list echo one another, step up the argument and its corresponding excitement in the audience as they move from one part to the next. The third part projects a completion point to cue the audience to get themselves ready to display their support via applause, cheers, and so forth. In a real conversation this juncture is called a “transition-relevance place,” at which point a conversational partner (hearer) may take up a turn to speak. A skilful orator will micropause at that juncture to create a conversational space for the audience to take up their turn in applauding and cheering as a group.

As illustrated by the two examples above, speaker and audience collaborate to transform an otherwise monological speech into a quasiconversation, turning a passive audience into an active supportive “conversational” partner who, by their synchronized responses, reduces the psychological separation from the speaker and emboldens the latter’s self-confidence. Through such enjoyable and emotional participation collectively, an audience made up of formerly unconnected individuals with no strong common group identity may henceforth begin to feel “we are all one.” According to social identity theory and related theories (van Zomeren et al., 2008 ), the emergent group identity, politicized in the process, will in turn provide a social psychological base for collective social action. This process of identity making in the audience is further strengthened by the speaker’s frequent use of “we” as a first person, plural personal pronoun.

Conversational Power

A conversation is a speech exchange system in which the length and order of speaking turns have not been preassigned but require coordination on an utterance-by-utterance basis between two or more individuals. It differs from other speech exchange systems in which speaking turns have been preassigned and/or monitored by a third party, for example, job interviews and debate contests. Turn-taking, because of its centrality to conversations and the important theoretical issues that it raises for social coordination and implicit conversational conventions, has been the subject of extensive research and theorizing (Goodwin & Heritage, 1990 ; Grice, 1975 ; Sacks et al., 1974 ). Success at turn-taking is a key part of the conversational process leading to influence. A person who cannot do this is in no position to influence others in and through conversations, which are probably the most common and ubiquitous form of human social interaction. Below we discuss studies of conversational power based on conversational turns and applied to leader emergence in group and intergroup settings. These studies, as they unfold, link conversation analysis with social identity theory and expectation states theory (Berger et al., 1974 ).

A conversational turn in hand allows the speaker to influence others in two important ways. First, through current-speaker-selects-next the speaker can influence who will speak next and, indirectly, increases the probability that he or she will regain the turn after the next. A common method for selecting the next speaker is through tag questions. The current speaker (A) may direct a tag question such as “Ya know?” or “Don’t you agree?” to a particular hearer (B), which carries the illocutionary force of selecting the addressee to be the next speaker and, simultaneously, restraining others from self-selecting. The A 1 B 1 sequence of exchange has been found to have a high probability of extending into A 1 B 1 A 2 in the next round of exchange, followed by its continuation in the form of A 1 B 1 A 2 B 2 . For example, in a six-member group, the A 1 B 1 →A 1 B 1 A 2 sequence of exchange has more than 50% chance of extending to the A 1 B 1 A 2 B 2 sequence, which is well above chance level, considering that there are four other hearers who could intrude at either the A 2 or B 2 slot of turn (Stasser & Taylor, 1991 ). Thus speakership not only offers the current speaker the power to select the next speaker twice, but also to indirectly regain a turn.

Second, a turn in hand provides the speaker with an opportunity to exercise topic control. He or she can exercise non-decision-making power by changing an unfavorable or embarrassing topic to a safer one, thereby silencing or preventing it from reaching the “floor.” Conversely, he or she can exercise decision-making power by continuing or raising a topic that is favorable to self. Or the speaker can move on to talk about an innocuous topic to ease tension in the group.